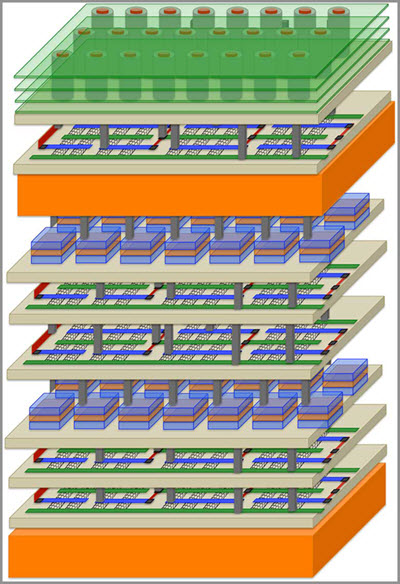

UW researchers have reconstructed 3-D models of celebrities such as Tom Hanks from large Internet photo collections. The models can also be controlled and animated by photos or videos of another person. (credit: University of Washington)

University of Washington researchers have demonstrated that it’s possible for machine learning algorithms to capture the “persona” and create a digital model of a well-photographed person like Tom Hanks from the vast number of images of them available on the Internet. With enough visual data to mine, the algorithms can also animate the digital model of Tom Hanks to deliver speeches that the real actor never performed.

Tom Hanks has appeared in many acting roles over the years, playing young and old, smart and simple. Yet we always recognize him as Tom Hanks. Why? Is it his appearance? His mannerisms? The way he moves? “One answer to what makes Tom Hanks look like Tom Hanks can be demonstrated with a computer system that imitates what Tom Hanks will do,” said lead author Supasorn Suwajanakorn, a UW graduate student in computer science and engineering.

The technology relies on advances in 3-D face reconstruction, tracking, alignment, multi-texture modeling, and puppeteering that have been developed over the last five years by a research group led by UW assistant professor of computer science and engineering Ira Kemelmacher-Shlizerman. The new results will be presented in an open-access paper at the International Conference on Computer Vision in Chile on Dec. 16.

Supasorn Suwajanakorn | What Makes Tom Hanks Look Like Tom Hanks

The team’s latest advances include the ability to transfer expressions and the way a particular person speaks onto the face of someone else — for instance, mapping former president George W. Bush’s mannerisms onto the faces of other politicians and celebrities.

It’s one step toward a grand goal shared by the UW computer vision researchers: creating fully interactive, three-dimensional digital personas from family photo albums and videos, historic collections or other existing visuals.

As virtual and augmented reality technologies develop, they envision using family photographs and videos to create an interactive model of a relative living overseas or a far-away grandparent, rather than simply Skyping in two dimensions.

“You might one day be able to put on a pair of augmented reality glasses and there is a 3-D model of your mother on the couch,” said senior author Kemelmacher-Shlizerman. “Such technology doesn’t exist yet — the display technology is moving forward really fast — but how do you actually re-create your mother in three dimensions?”

One day the reconstruction technology could be taken a step further, researchers say.

“Imagine being able to have a conversation with anyone you can’t actually get to meet in person — LeBron James, Barack Obama, Charlie Chaplin — and interact with them,” said co-author Steve Seitz, UW professor of computer science and engineering. “We’re trying to get there through a series of research steps. One of the true tests is can you have them say things that they didn’t say but it still feels like them? This paper is demonstrating that ability.”

Supasorn Suwajanakorn | George Bush driving crowd

Existing technologies to create detailed three-dimensional holograms or digital movie characters like Benjamin Button often rely on bringing a person into an elaborate studio. They painstakingly capture every angle of the person and the way they move — something that can’t be done in a living room.

Other approaches still require a person to be scanned by a camera to create basic avatars for video games or other virtual environments. But the UW computer vision experts wanted to digitally reconstruct a person based solely on a random collection of existing images.

Learning in the wild

To reconstruct celebrities like Tom Hanks, Barack Obama and Daniel Craig, the machine learning algorithms mined a minimum of 200 Internet images taken over time in various scenarios and poses — a process known as learning “in the wild.”

“We asked, ‘Can you take Internet photos or your personal photo collection and animate a model without having that person interact with a camera?’” said Kemelmacher-Shlizerman. “Over the years we created algorithms that work with this kind of unconstrained data, which is a big deal.”

Suwajanakorn more recently developed techniques to capture expression-dependent textures — small differences that occur when a person smiles or looks puzzled or moves his or her mouth, for example.

By manipulating the lighting conditions across different photographs, he developed a new approach to densely map the differences from one person’s features and expressions onto another person’s face. That breakthrough enables the team to “control” the digital model with a video of another person, and could potentially enable a host of new animation and virtual reality applications.

“How do you map one person’s performance onto someone else’s face without losing their identity?” said Seitz. “That’s one of the more interesting aspects of this work. We’ve shown you can have George Bush’s expressions and mouth and movements, but it still looks like George Clooney.”

Perhaps this could be used to create VR experiences by integrating the animated images in 360-degree sets?

Abstract of What Makes Tom Hanks Look Like Tom Hanks

We reconstruct a controllable model of a person from a large photo collection that captures his or her persona, i.e., physical appearance and behavior. The ability to operate on unstructured photo collections enables modeling a huge number of people, including celebrities and other well photographed people without requiring them to be scanned. Moreover, we show the ability to drive or puppeteer the captured person B using any other video of a different person A. In this scenario, B acts out the role of person A, but retains his/her own personality and character. Our system is based on a novel combination of 3D face reconstruction, tracking, alignment, and multi-texture modeling, applied to the puppeteering problem. We demonstrate convincing results on a large variety of celebrities derived from Internet imagery and video.