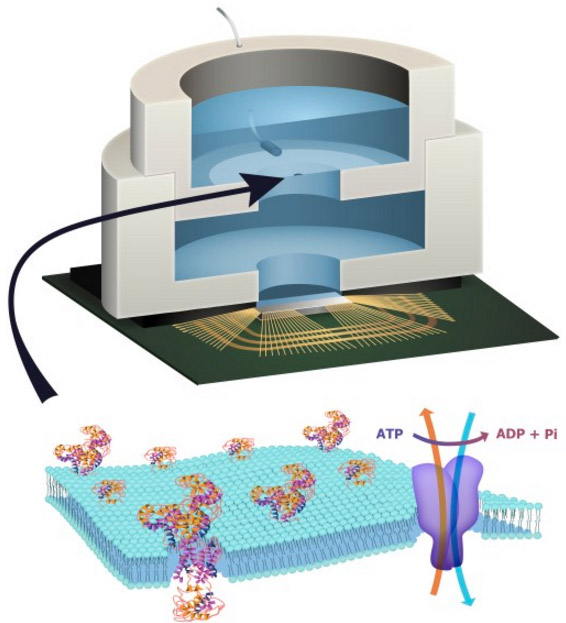

Illustration depicting a biocell attached to a CMOS integrated circuit with a membrane containing sodium-potassium pumps in pores. Energy is stored chemically in ATP molecules. When the energy is released as charged ions (which are then converted to electrons to power the chip at the bottom of the experimental device), the ATP is converted to ADP + inorganic phosphate. (credit: Trevor Finney and Jared Roseman/Columbia Engineering)

Columbia Engineering researchers have combined biological and solid-state components for the first time, opening the door to creating entirely new artificial biosystems.

In this experiment, they used a biological cell to power a conventional solid-state complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integrated circuit. An artificial lipid bilayer membrane containing adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-powered ion pumps (which provide energy for cells) was used as a source of ions (which were converted to electrons to power the chip).

The study, led by Ken Shepard, Lau Family Professor of Electrical Engineering and professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia Engineering, was published online today (Dec. 7, 2015) in an open-access paper in Nature Communications.

How to build a hybrid biochip

Living systems achieve this functionality with their own version of electronics based on lipid membranes and ion channels and pumps, which act as a kind of “biological transistor.” Charge in the form of ions carry energy and information, and ion channels control the flow of ions across cell membranes.

Solid-state systems, such as those in computers and communication devices, use electrons; their electronic signaling and power are controlled by field-effect transistors.

To build a prototype of their hybrid system, Shepard’s team packaged a CMOS integrated circuit (IC) with an ATP-harvesting “biocell.” In the presence of ATP, the system pumped ions across the membrane, producing an electrical potential (voltage)* that was harvested by the integrated circuit.

“We made a macroscale version of this system, at the scale of several millimeters, to see if it worked,” Shepard notes. “Our results provide new insight into a generalized circuit model, enabling us to determine the conditions to maximize the efficiency of harnessing chemical energy through the action of these ion pumps. We will now be looking at how to scale the system down.”

While other groups have harvested energy from living systems, Shepard and his team are exploring how to do this at the molecular level, isolating just the desired function and interfacing this with electronics. “We don’t need the whole cell,” he explains. “We just grab the component of the cell that’s doing what we want. For this project, we isolated the ATPases because they were the proteins that allowed us to extract energy from ATP.”

The capability of a bomb-sniffing dog, no Alpo required

Next, the researchers plan to go much further, such as recognizing specific molecules and giving chips the potential to taste and smell.

The ability to build a system that combines the power of solid-state electronics with the capabilities of biological components has great promise, they believe. “You need a bomb-sniffing dog now, but if you can take just the part of the dog that is useful — the molecules that are doing the sensing — we wouldn’t need the whole animal,” says Shepard.

The technology could also provide a power source for implanted electronic devices in ATP-rich environments such as inside living cells, the researchers suggest.

* “In general, integrated circuits, even when operated at the point of minimum energy in subthreshold, consume on the order of 10−2 W mm−2 (or assuming a typical silicon chip thickness of 250 μm, 4 × 10−2 W mm−3). Typical cells, in contrast, consume on the order of 4 × 10−6 W mm−3. In the experiment, a typical active power dissipation for the IC circuit was 92.3 nW, and the active average harvesting power was 71.4 fW for the biocell (the discrepancy is managed through duty-cycled operation of the IC).” — Jared M. Roseman et al./Nature Communications