Camera test at Foljesjon, a lake in a research area west of Vanersborg, Sweden (credit: Linkoping University)

A new camera that can image methane in the air, allowing for precision monitoring of a greenhouse gas, has been developed by a team of researchers from Linköping and Stockholm Universities.

The new camera should help us better understand the rapid but irregular increase of methane in the atmosphere (which has puzzled researchers) and identify the sources and sinks of methane in the landscape. It may also suggest ways to reduce emissions.

”The camera is very sensitive, which means that the methane is both visible and measureable close to ground level, with much higher resolution [less than a square meter and at ambient levels (~1.8 ppmv, or parts per million volume)] than previously. Being able to measure on a small scale is crucial,” says Magnus Gålfalk, Assistant Professor at Tema Environmental Change, Linköping University who led the study.

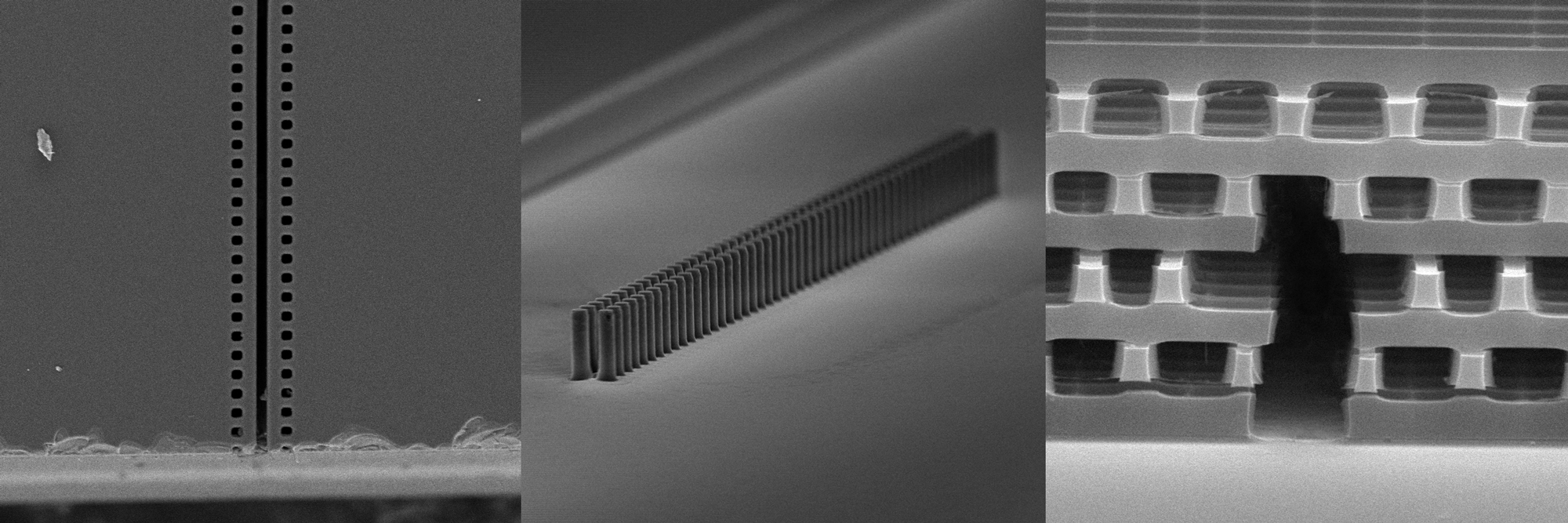

An image of methane gas from the hyperspectral infrared camera, visualized in purple (credit: Linköping University)

The advanced hyperspectral (across the spectrum) thermal infrared camera weighs 30 kilos and measures 50 x 45 x 25 centimeters. It is optimized to measure the same portion of the solar radiation spectrum that methane absorbs and which makes methane such a powerful greenhouse gas.

The camera can be used to measure emissions from many environments including sewage sludge deposits, combustion processes, animal husbandry, and lakes.

For each pixel in the image (320 x 256 pixels), the camera records a precise spectrum range (in the 7.7 microns thermal IR region), which makes it possible to quantify the methane separately from the other gases.

The camera was developed by a team with expertise in astronomy, biogeochemistry, engineering. and environmental sciences. “We’re working to make it airborne for more large-scale methane mapping,” says principal investigator David Bastviken, professor at Tema Environmental Change, Linköping University.

The research was recently published in Nature Climate Change.

Super-absorbent material to soak up oil spills

Boron nitride material supported by a plant spike, demonstrating its light weight (credit: Weiwei Lei et al./Nature Communications)

In hopes of limiting the disastrous environmental effects of massive oil spills, materials scientists from Drexel University and Deakin University (Australia) have teamed up to manufacture and test a new “boron nitride nanosheet” material that can absorb oils and organic solvents up to 33 times its weight. That could make it possible to quickly mitigate these costly, environmentally damaging accidents.

The material, which literally absorbs oil like a sponge, is now ready to be tested by industry after two years of refinement in the laboratory at Deakin’s Institute for Frontier Materials (IFM).

Deakin Professor Ying (Ian) Chen, PhD, the lead author of the project’s research paper, recently published in Nature Communications, said the material is the most exciting advancement in oil spill remediation technology in decades.

“Oil spills are a global problem and wreak havoc on our aquatic ecosystems, not to mention they cost billions of dollars in damage,” Chen said. “Everyone remembers the Gulf Coast disaster, but here in Australia they are a regular problem, and not just in our waters. Oil spills from trucks and other vehicles can close freeways for an entire day, again amounting to large economic losses,” Chen said.

The nanosheet is made up of flakes just several nanometers (one billionth of a meter) in thickness with tiny holes. This strecture enables the nanosheet to increase its effective surface area to 273 square meters (3000 square feet) per gram.

Researchers from Drexel’s College of Engineering helped to study and functionalize the material, which started as boron nitride powder, commonly called “white graphite.” By forming the powder into atomically thin sheets, the material could be made into a sponge.

“The mechanochemical technique developed meant it was possible to produce high-concentration stable aqueous colloidal solutions of boron nitride sheets, which could then be transformed into the ultralight porous aerogels and membranes for oil clean-up,” said Vadym Mochalin, PhD, a co-author of the paper, who was a research associate professor at Drexel while working on the project, and is now an associate professor at Missouri University of Science and Technology.

The Drexel team used computational modeling to help understand the intimate details of how the material was formed. In the process, the team learned that the boron nitride nanosheets are flame resistant — which means they could also find applications in electrical and heat insulation.

The nanotechnology team at Deakin’s Institute for Frontier Materials has been working on boron nitride nanomaterials for two decades and has been internationally recognized for its work in the development of boron nitride nanotubes and nanosheets. This project is the next step in the IFM’s continued research to discover new uses for the material.

Abstract of Making methane visible

Methane (CH4) is one of the most important greenhouse gases, and an important energy carrier in biogas and natural gas. Its large-scale emission patterns have been unpredictable and the source and sink distributions are poorly constrained. Remote assessment of CH4 with high sensitivity at a m2 spatial resolution would allow detailed mapping of the near-ground distribution and anthropogenic sources in landscapes but has hitherto not been possible. Here we show that CH4 gradients can be imaged on the <m2scale at ambient levels (~1.8 ppm) and filmed using optimized infrared (IR) hyperspectral imaging. Our approach allows both spectroscopic confirmation and quantification for all pixels in an imaged scene simultaneously. It also has the ability to map fluxes for dynamic scenes. This approach to mapping boundary layer CH4 offers a unique potential way to improve knowledge about greenhouse gases in landscapes and a step towards resolving source–sink attribution and scaling issues.

Abstract of Boron nitride colloidal solutions, ultralight aerogels and freestanding membranes through one-step exfoliation and functionalization

Manufacturing of aerogels and membranes from hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) is much more difficult than from graphene or graphene oxides because of the poor dispersibility of h-BN in water, which limits its exfoliation and preparation of colloidal solutions. Here, a simple, one-step mechano-chemical process to exfoliate and functionalize h-BN into highly water-dispersible, few-layer h-BN containing amino groups is presented. The colloidal solutions of few-layer h-BN can have unprecedentedly high concentrations, up to 30 mg ml−1, and are stable for up to several months. They can be used to produce ultralight aerogels with a density of 1.4 mg cm−3, which is ~1,500 times less than bulk h-BN, and freestanding membranes simply by cryodrying and filtration, respectively. The material shows strong blue light emission under ultraviolet excitation, in both dispersed and dry state.

fidelity) and deterministically prepare them into the maximally entangled Bell states (with 0.88 ± 0.07 fidelity). To verify entanglement, we develop a register-specific quantum-state tomography protocol. The entanglement of a macroscopic solid-state spin ensemble at ambient conditions represents an important step toward practical quantum technology.

fidelity) and deterministically prepare them into the maximally entangled Bell states (with 0.88 ± 0.07 fidelity). To verify entanglement, we develop a register-specific quantum-state tomography protocol. The entanglement of a macroscopic solid-state spin ensemble at ambient conditions represents an important step toward practical quantum technology.