Colistin antibiotic overused in farm animals in China apparently caused E-coli bacteria to become completely resistant to treatment; E-coli strain has already spread to Laos and Malaysia (credit: Yi-Yun Liu et al./Lancet Infect Dis)

Widespread E-coli bacteria that cannot be killed with the antiobiotic drug of last resort — colistin — have been found in samples taken from farm pigs, meat products, and a small number of patients in south China, including bacterial strains with epidemic potential, an international team of scientists revealed in a paper published Thursday Nov. 19 in the journal The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

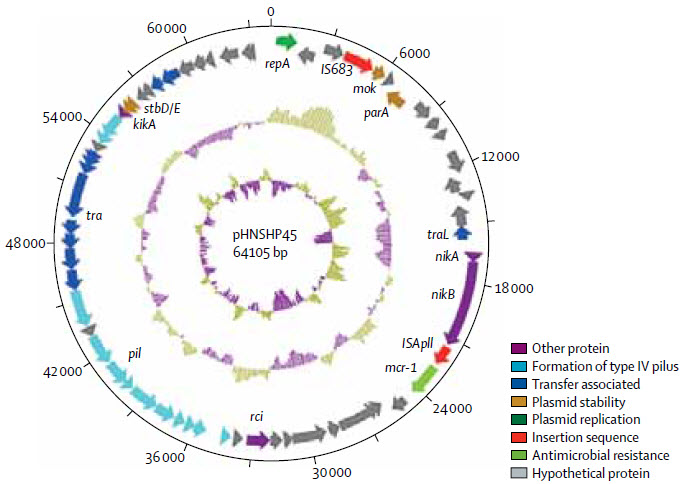

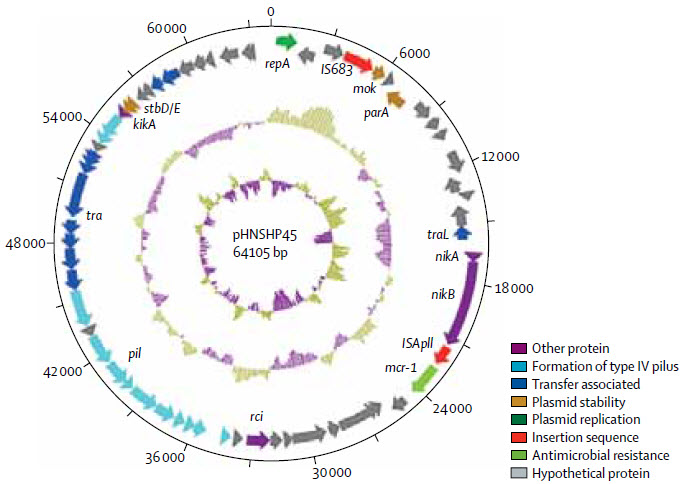

The scientists in China, England, and the U.S. found a new gene, MCR-1, carried in E-coli bacteria strain SHP45. MCR-1 enables bacteria to be highly resistant to colistin and other polymyxins drugs.

“The emergence of the MCR-1 gene in China heralds a disturbing breach of the last group of antibiotics — polymixins — and an end to our last line of defense against infection,” said Professor Timothy Walsh, from the Cardiff University School of Medicine, who collaborated on this research with scientists from South China Agricultural University.

Walsh, an expert in antibiotic resistance, is best known for his discovery in 2011 of the NDM-1 disease-causing antibiotic-resistant superbug in New Delhi’s drinking water supply. “The rapid spread of similar antibiotic-resistant genes such as NDM-1 suggests that all antibiotics will soon be futile in the face of previously treatable gram-negative bacterial infections such as E.coli and salmonella,” he said.

Likely to spread worldwide; already found in Laos and Malaysia

The MCR-1 gene was found on plasmids — mobile DNA that can be easily copied and transferred between different bacteria, suggesting an alarming potential to spread and diversify between different bacterial populations.

Structure of plasmid pHNSHP45 carrying MCR-1 from Escherichia coli strain SHP45 (credit: Yi-Yun Liu et al./Lancet Infect Dis)

“We now have evidence to suggest that MCR-1-positive E.coli has spread beyond China, to Laos and Malaysia, which is deeply concerning,” said Walsh. “The potential for MCR-1 to become a global issue will depend on the continued use of polymixin antibiotics, such as colistin, on animals, both in and outside China; the ability of MCR-1 to spread through human strains of E.coli; and the movement of people across China’s borders.”

“MCR-1 is likely to spread to the rest of the world at an alarming rate unless we take a globally coordinated approach to combat it. In the absence of new antibiotics against resistant gram-negative pathogens, the effect on human health posed by this new gene cannot be underestimated.”

“Of the top ten largest producers of colistin for veterinary use, one is Indian, one is Danish, and eight are Chinese,” The Lancet Infectious Diseases notes. “Asia (including China) makes up 73·1% of colistin production with 28·7% for export including to Europe.29 In 2015, the European Union and North America imported 480 tonnes and 700 tonnes, respectively, of colistin from China.”

Urgent need for coordinated global action

“Our findings highlight the urgent need for coordinated global action in the fight against extensively resistant and pan-resistant gram-negative bacteria,” the journal paper concludes.

“The implications of this finding are enormous,” an associated editorial comment to the The Lancet Infectious Diseases paper stated. “We must all reiterate these appeals and take them to the highest levels of government or face increasing numbers of patients for whom we will need to say, ‘Sorry, there is nothing I can do to cure your infection.’”

Margaret Chan, MD, Director-General of the World Health Organization, warned in 2011 that “the world is heading towards a post-antibiotic era, in which many common infections will no longer have a cure and, once again, kill unabated.”

“Although in its 2012 World Health Organization Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (AGISAR) report the WHO concluded that colistin should be listed under those antibiotics of critical importance, it is regrettable that in the 2014 Global Report on Surveillance, the WHO did not to list any colistin-resistant bacteria as part of their ‘selected bacteria of international concern,’” The Lancet Infectious Diseases paper says, reflecting WHO’s inaction in Ebola-stricken African countries, as noted last September by the international medical humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières.

Funding for the E-coli bacteria study was provided by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Abstract of Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study

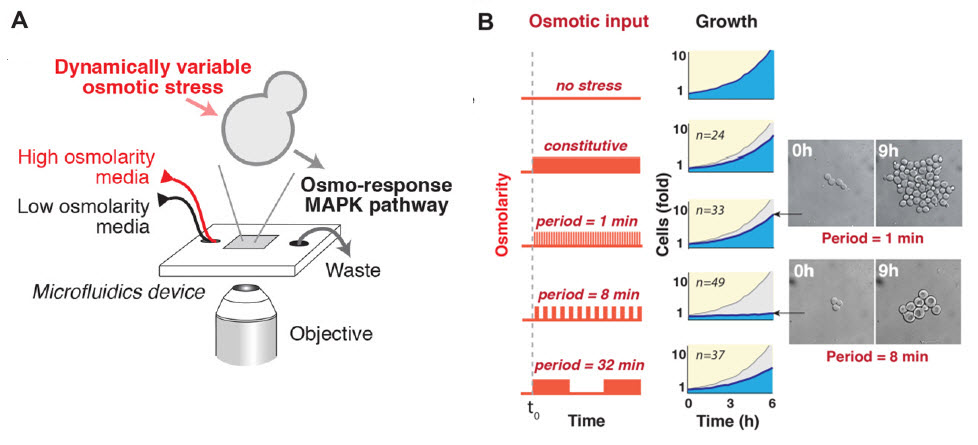

Until now, polymyxin resistance has involved chromosomal mutations but has never been reported via

horizontal gene transfer. During a routine surveillance project on antimicrobial resistance in commensal Escherichia coli from food animals in China, a major increase of colistin resistance was observed. When an E coli strain, SHP45, possessing colistin resistance that could be transferred to another strain, was isolated from a pig, we conducted further analysis of possible plasmid-mediated polymyxin resistance. Herein, we report the emergence of the first plasmid-mediated polymyxin resistance mechanism, MCR-1, in Enterobacteriaceae.

The mcr-1 gene in E coli strain SHP45 was identified by whole plasmid sequencing and subcloning. MCR-1 mechanistic studies were done with sequence comparisons, homology modelling, and electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. The prevalence of mcr-1 was investigated in E coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains collected from five provinces between April, 2011, and November, 2014. The ability of MCR-1 to confer polymyxin resistance in vivo was examined in a murine thigh model.

Polymyxin resistance was shown to be singularly due to the plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene. The plasmid carrying mcr-1 was mobilised to an E coli recipient at a frequency of 10−1 to 10−3 cells per recipient cell by conjugation, and maintained in K pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In an in-vivo model, production of MCR-1 negated the efficacy of colistin. MCR-1 is a member of the phosphoethanolamine transferase enzyme family, with expression in E coli resulting in the addition of phosphoethanolamine to lipid A. We observed mcr-1 carriage in E coli isolates collected from 78 (15%) of 523 samples of raw meat and 166 (21%) of 804 animals during 2011–14, and 16 (1%) of 1322 samples from inpatients with infection.

The emergence of MCR-1 heralds the breach of the last group of antibiotics, polymyxins, by plasmid-mediated resistance. Although currently confined to China, MCR-1 is likely to emulate other global resistance mechanisms such as NDM-1. Our findings emphasise the urgent need for coordinated global action in the fight against pan-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria.