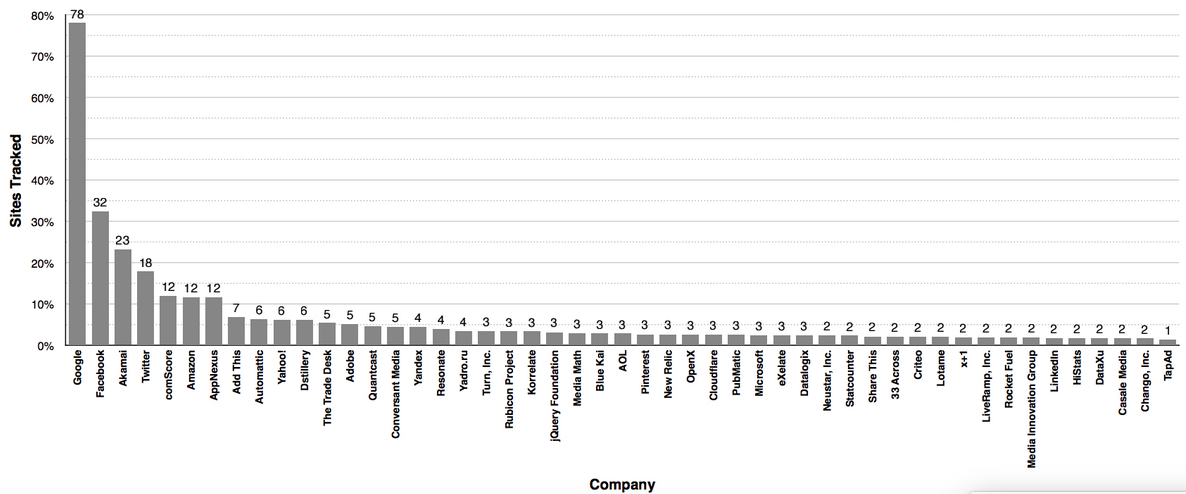

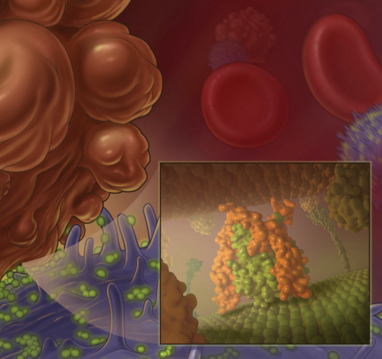

Effect of drug treatment on AD mice in control group (left) or drug (right) on Ab plaque load. (credit: Cheng Zhang et al./Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association)

In a novel animal study design that mimicked human clinical trials, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine report that long-term treatment using a small-molecule drug that reduces activity of the brain’s stress circuitry significantly reduces Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathology and prevents onset of cognitive impairment in a mouse model of the neurodegenerative condition.

The findings are described in the current online issue of the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.

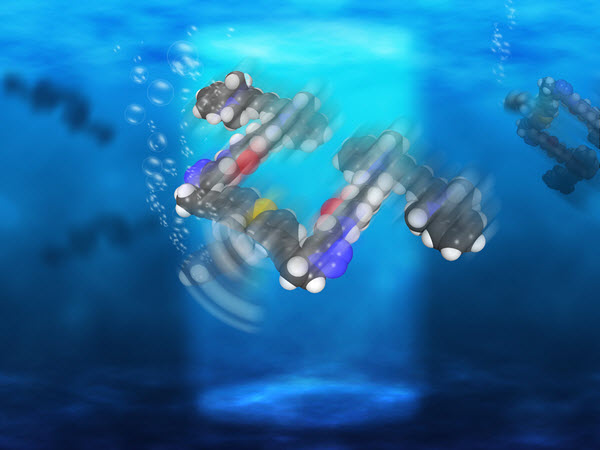

Previous research has shown a link between the brain’s stress signaling pathways and AD. Specifically, the release of a stress-coping hormone called corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), which is widely found in the brain and acts as a neurotransmitter/neuromodulator, is dysregulated in AD and is associated with impaired cognition and with detrimental changes in tau protein and increased production of amyloid-beta protein fragments that clump together and trigger the neurodegeneration characteristic of AD.

“Our work and that of our colleagues on stress and CRF have been mechanistically implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, but agents that impact CRF signaling have not been carefully tested for therapeutic efficacy or long-term safety in animal models,” said the study’s principal investigator and corresponding author Robert Rissman, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Neurosciences and Biomarker Core Director for the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS).

The researchers determined that modulating the mouse brain’s stress circuitry mitigated generation and accumulation of amyloid plaques widely attributed with causing neuronal damage and death. As a consequence, behavioral indicators of AD were prevented and cellular damage was reduced. The mice began treatment at 30-days-old — before any pathological or cognitive signs of AD were present — and continued until six months of age.

One particular challenge, Rissman noted, is limiting exposure of the drug to the brain so that it does not impact the body’s ability to respond to stress. “This can be accomplished because one advantage of these types of small molecule drugs is that they readily cross the blood-brain barrier and actually prefer to act in the brain,” Rissman said.

“Rissman’s prior work demonstrated that CRF and its receptors are integrally involved in changes in another AD hallmark, tau phosphorylation,” said William Mobley, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Neurosciences and interim co-director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at UC San Diego. “This new study extends those original mechanistic findings to the amyloid pathway and preservation of cellular and synaptic connections. Work like this is an excellent example of UC San Diego’s bench-to-bedside legacy, whereby we can quickly move our basic science findings into the clinic for testing,” said Mobley.

Rissman said R121919 was well-tolerated by AD mice (no significant adverse effects) and deemed safe, suggesting CRF-antagonism is a viable, disease-modifying therapy for AD. Drugs like R121919 were originally designed to treat generalized anxiety disorder, irritable bowel syndrome and other diseases, but failed to be effective in treating those disorders.

Rissman noted that repurposing R121919 for human use was likely not possible at this point. He and colleagues are collaborating with the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute to design new assays to discover the next generation of CRF receptor-1 antagonists for testing in early phase human safety trials.

“More work remains to be done, but this is the kind of basic research that is fundamental to ultimately finding a way to cure — or even prevent —Alzheimer’s disease,” said David Brenner, MD, vice chancellor, UC San Diego Health Sciences and dean of UC San Diego School of Medicine. “These findings by Dr. Rissman and his colleagues at UC San Diego and at collaborating institutions on the Mesa suggest we are on the cusp of creating truly effective therapies.”

Abstract of Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-1 antagonism mitigates beta amyloid pathology and cognitive and synaptic deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction: Stress and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) have been implicated as mechanistically involved in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but agents that impact CRF signaling have not been carefully tested for therapeutic efficacy or long-term safety in animal models.

Methods: To test whether antagonism of the type-1 corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRFR1) could be used as a disease-modifying treatment for AD, we used a preclinical prevention paradigm and treated 30-day-old AD transgenic mice with the small-molecule, CRFR1-selective antagonist, R121919, for 5 months, and examined AD pathologic and behavioral end points.

Results: R121919 significantly prevented the onset of cognitive impairment in female mice and reduced cellular and synaptic deficits and beta amyloid and C-terminal fragment-β levels in both genders. We observed no tolerability or toxicity issues in mice treated with R121919.

Discussion: CRFR1 antagonism presents a viable disease-modifying therapy for AD, recommending its advancement to early-phase human safety trials.