False-color microscopic view of a reduced graphene oxide electrode (black), which hosts the large (about 20 micrometers) lithium hydroxide particles (pink) that form when a lithium-oxygen battery discharges (credit: T. Liu et al./Science)

University of Cambridge scientists have developed a working laboratory demonstrator of a lithium-oxygen battery that has very high energy density (storage capacity per unit volume), is more than 90% efficient, and can be recharged more than 2000 times (so far), showing how several of the problems holding back the development of more powerful batteries could be solved.

Lithium-oxygen (lithium-air) batteries have been touted as the “ultimate” battery due to their theoretical energy density, which is ten times higher than a lithium-ion battery. Such a high energy density would be comparable to that of gasoline — allowing for an electric car with a battery that is a fifth the cost and a fifth the weight of those currently on the market and that could drive about 666 km (414 miles) on a single charge. (This compares to 500 kilometers (311 miles) with the new University of Waterloo design, using a silicon anode — see “Longer-lasting, lighter lithium-ion batteries from silicon anodes.”)

The challenges associated with making a better battery are holding back the widespread adoption of two major clean technologies: electric cars and grid-scale storage for solar power.

A lab demonstrator based on graphene

The researchers have now demonstrated how some of the obstacles to the ultimate battery could be overcome in a lab-based demonstrator of a lithium-oxygen battery with higher capacity, increased energy efficiency, and improved stability over previous attempts.

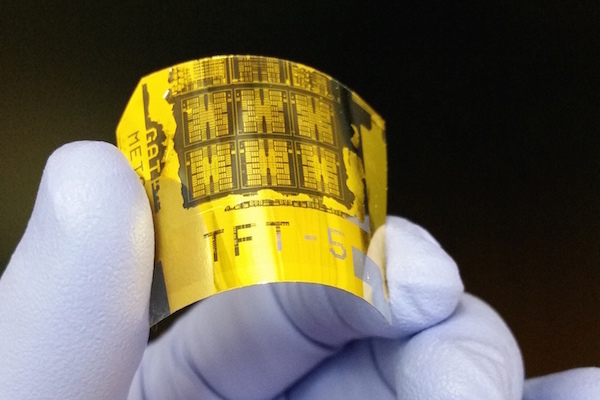

SEM images of pristine, fully discharged, and charged reduced graphene oxide electrodes in lab demonstrator. Scale bars: 20 micrometers. (credit: Tao Liu et al./Science)

Their demonstrator relies on a highly porous, “fluffy” carbon electrode made from reduced graphene oxide (comprising one-atom-thick sheets of carbon atoms), and additives that alter the chemical reactions at work in the battery, making it more stable and more efficient. While the results, reported in the journal Science, are promising, the researchers caution that a practical lithium-air battery still remains at least a decade away.

“What we’ve achieved is a significant advance for this technology and suggests whole new areas for research — we haven’t solved all the problems inherent to this chemistry, but our results do show routes forward towards a practical device,” said Professor Clare Grey of Cambridge’s Department of Chemistry, the paper’s senior author.

Batteries are made of three components: a positive electrode, a negative electrode and an electrolyte. In the lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries currently used in laptops and smartphones, the negative electrode is made of graphite (a form of carbon), the positive electrode is made of a metal oxide, such as lithium cobalt oxide, and the electrolyte is a lithium salt dissolved in an organic solvent. The action of the battery depends on the movement of lithium ions between the electrodes. Li-ion batteries are light, but their capacity deteriorates with age, and their relatively low energy densities mean that they need to be recharged frequently.

Over the past decade, researchers have been developing various alternatives to Li-ion batteries, and lithium-air batteries are considered the ultimate in next-generation energy storage, because of their extremely high theoretical energy density. However, attempts at working demonstrators so far have had low efficiency, poor rate performance, and unwanted chemical reactions. Also, they can only be cycled in pure oxygen.

What Liu, Grey and their colleagues have developed uses a very different chemistry: lithium hydroxide (LiOH) instead of lithium peroxide (Li2O2). With the addition of water and the use of lithium iodide as a “mediator,” their battery showed far less of the chemical reactions which can cause cells to die, making it far more stable after multiple charge and discharge cycles.

By precisely engineering the structure of the electrode, changing it to a highly porous form of graphene, adding lithium iodide, and changing the chemical makeup of the electrolyte, the researchers were able to reduce the “voltage gap” between charge and discharge to 0.2 volts. A small voltage gap equals a more efficient battery. Previous versions of a lithium-air battery have only managed to get the gap down to 0.5 – 1.0 volts, whereas 0.2 volts is closer to that of a Li-ion battery, and equates to an energy efficiency of 93%.

Problems to be solved

The highly porous graphene electrode also greatly increases the capacity of the demonstrator, although only at certain rates of charge and discharge. Other issues that still have to be addressed include finding a way to protect the metal electrode so that it doesn’t form spindly lithium metal fibers known as dendrites, which can cause batteries to explode if they grow too much and short-circuit the battery.

Additionally, the demonstrator can only be cycled in pure oxygen, while the air around us also contains carbon dioxide, nitrogen and moisture, all of which are generally harmful to the metal electrode.

The authors acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Johnson Matthey, the European Union via Marie Curie Actions, and the Graphene Flagship. The technology has been patented and is being commercialized through Cambridge Enterprise, the University’s commercialization arm.

Abstract of Cycling Li-O2 batteries via LiOH formation and decomposition

The rechargeable aprotic lithium-air (Li-O2) battery is a promising potential technology for next-generation energy storage, but its practical realization still faces many challenges. In contrast to the standard Li-O2 cells, which cycle via the formation of Li2O2, we used a reduced graphene oxide electrode, the additive LiI, and the solvent dimethoxyethane to reversibly form and remove crystalline LiOH with particle sizes larger than 15 micrometers during discharge and charge. This leads to high specific capacities, excellent energy efficiency (93.2%) with a voltage gap of only 0.2 volt, and impressive rechargeability. The cells tolerate high concentrations of water, water being the dominant proton source for the LiOH; together with LiI, it has a decisive impact on the chemical nature of the discharge product and on battery performance.

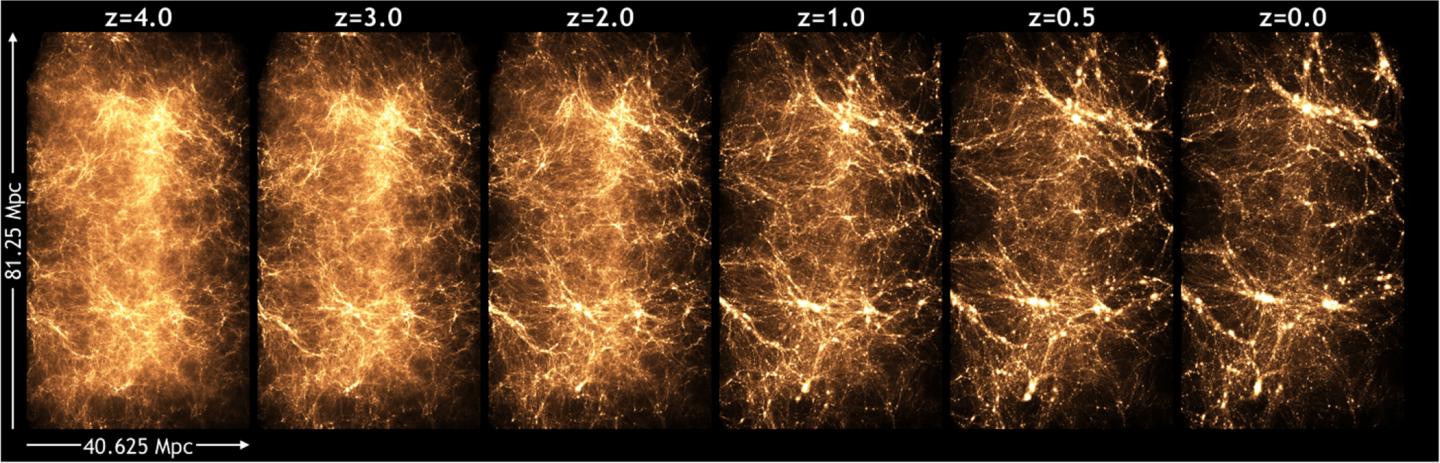

. At this mass resolution, the Q Continuum run is currently the largest cosmology simulation available. It enables the construction of detailed synthetic sky catalogs, encompassing different modeling methodologies, including semi-analytic modeling and sub-halo abundance matching in a large, cosmological volume. Here we describe the simulation and outputs in detail and present first results for a range of cosmological statistics, such as mass power spectra, halo mass functions, and halo mass-concentration relations for different epochs. We also provide details on challenges connected to running a simulation on almost 90% of Titan, one of the fastest supercomputers in the world, including our usage of Titan’s GPU accelerators.

. At this mass resolution, the Q Continuum run is currently the largest cosmology simulation available. It enables the construction of detailed synthetic sky catalogs, encompassing different modeling methodologies, including semi-analytic modeling and sub-halo abundance matching in a large, cosmological volume. Here we describe the simulation and outputs in detail and present first results for a range of cosmological statistics, such as mass power spectra, halo mass functions, and halo mass-concentration relations for different epochs. We also provide details on challenges connected to running a simulation on almost 90% of Titan, one of the fastest supercomputers in the world, including our usage of Titan’s GPU accelerators.