(credit: DARPA)

Neuroscientists in a project headed by the University of Chicago have determined some of the specific characteristics of electrical stimuli that should be applied to the brain to produce different sensations in an artificial upper limb intended to restore natural motor control and sensation in amputees.

The research is part of Revolutionizing Prosthetics, a multi-year Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

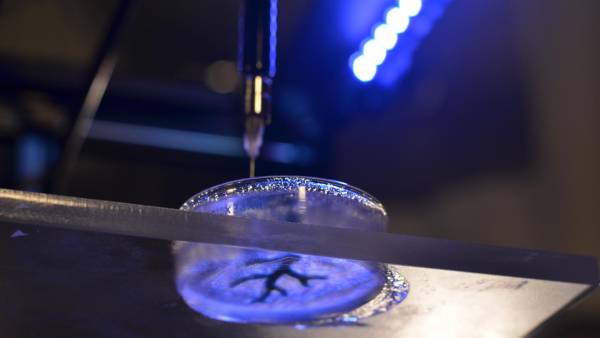

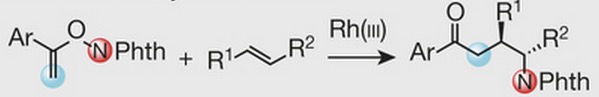

Experimental setup for investigating the ability of monkeys to detect and discriminate trains of electrical pulses delivered to their somatosensory cortex through chronically implanted electrode arrays (credit: Sungshin Kima et al./PNAS)

For this study, the researchers used monkeys, whose sensory systems closely resemble those of humans. They implanted electrodes into the primary somatosensory cortex, the area of the brain that processes touch information from the hand. The animals were trained to perform two perceptual tasks: one in which they detected the presence of an electrical stimulus, and a second task in which they indicated which of two successive stimuli was more intense.

The sense of touch is made up of a complex and nuanced set of sensations, from contact and pressure to texture, vibration and movement. The goal of the research is to document the range, composition and specific increments of signals that create sensations that feel different from each other.

Chronically implanted electrode arrays in a monkey brain. (Left) one 96-electrode array (UEA) was implanted in area 1 (green) of the somatosensory cortex and two 16-electrode arrays (FMA) were implanted in area 3b (yellow). (Center) Colors correspond to the 96 and 16 electrodes. (Right) Colors indicate which electrodes mapped to corresponding hand areas. (credit: Sungshin Kima et al./PNAS)

To achieve that, the researchers manipulated various features of the electrical pulse train, such as its amplitude, frequency, and duration, and noted how the interaction of each of these factors affected the animals’ ability to detect the signal.

Of specific interest were the “just-noticeable differences” (JND),” — the incremental changes needed to produce a sensation that felt different. For instance, at a certain frequency, the signal may be detectable first at a strength of 20 microamps of electricity. If the signal has to be increased to 50 microamps to notice a difference, the JND in that case is 30 microamps.*

“When you grasp an object, for example, you can hold it with different grades of pressure. To recreate a realistic sense of touch, you need to know how many grades of pressure you can convey through electrical stimulation,” said Sliman Bensmaia, PhD, Associate Professor in the Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago and senior author of the study, which was published today (Oct. 26) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Ideally, you can have the same dynamic range for artificial touch as you do for natural touch.”

“This study gets us to the point where we can actually create real algorithms that work. It gives us the parameters as to what we can achieve with artificial touch, and brings us one step closer to having human-ready algorithms.”

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh and Johns Hopkins University were also involved in the DARPA-supported study.

* The study also has important scientific implications beyond neuroprosthetics. In natural perception, a principle known as Weber’s Law states that the just-noticeable difference between two stimuli is proportional to the size of the stimulus. For example, with a 100-watt light bulb, you might be able to detect a difference in brightness by increasing its power to 110 watts. The JND in that case is 10 watts. According to Weber’s Law, if you double the power of the light bulb to 200 watts, the JND would also be doubled to 20 watts.

However, Bensmaia’s research shows that with electrical stimulation of the brain, Weber’s Law does not apply — the JND remains nearly constant, no matter the size of the stimulus. This means that the brain responds to electrical stimulation in a much more repeatable, consistent way than through natural stimulation.

“It shows that there is something fundamentally different about the way the brain responds to electrical stimulation than it does to natural stimulation,” Bensmaia said.

Abstract of Behavioral assessment of sensitivity to intracortical microstimulation of primate somatosensory cortex

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) is a powerful tool to investigate the functional role of neural circuits and may provide a means to restore sensation for patients for whom peripheral stimulation is not an option. In a series of psychophysical experiments with nonhuman primates, we investigate how stimulation parameters affect behavioral sensitivity to ICMS. Specifically, we deliver ICMS to primary somatosensory cortex through chronically implanted electrode arrays across a wide range of stimulation regimes. First, we investigate how the detectability of ICMS depends on stimulation parameters, including pulse width, frequency, amplitude, and pulse train duration. Then, we characterize the degree to which ICMS pulse trains that differ in amplitude lead to discriminable percepts across the range of perceptible and safe amplitudes. We also investigate how discriminability of pulse amplitude is modulated by other stimulation parameters—namely, frequency and duration. Perceptual judgments obtained across these various conditions will inform the design of stimulation regimes for neuroscience and neuroengineering applications.