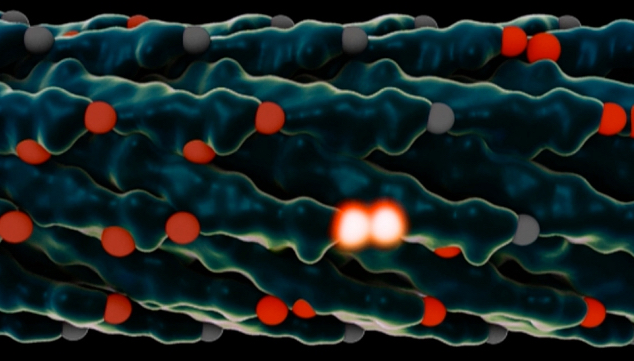

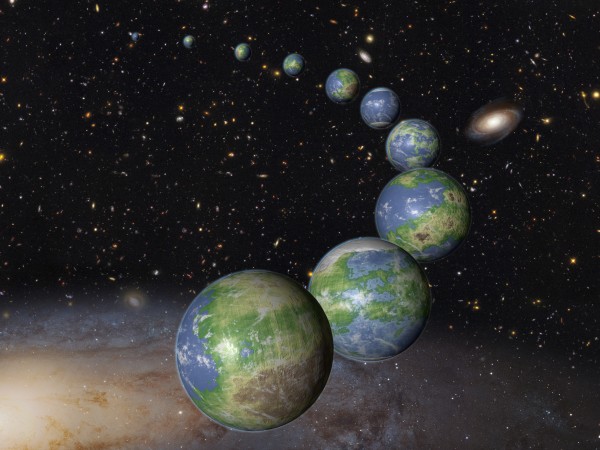

This is an artist’s impression of innumerable Earth-like planets that have yet to be born over the next trillion years in the evolving universe (credit: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI); Science: NASA, ESA, P. Behroozi and M. Peeples (STScI))

When our solar system was born 4.6 billion years ago, only eight percent of the potentially habitable planets that will ever form in the universe existed, according to an assessment of data collected by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and Kepler space observatory and published today (Oct. 20) in an open-access paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

In related news, UCLA geochemists have found evidence that life probably existed on Earth at least 4.1 billion years ago, which is 300 million years earlier than previous research suggested. The research suggests life in the universe could be abundant, said Mark Harrison, co-author of the research and a professor of geochemistry at UCLA. The research was published Monday Oct. 19 in the online early edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The data show that the universe was making stars at a fast rate 10 billion years ago, but the fraction of the universe’s hydrogen and helium gas that was involved was very low. Today, star birth is happening at a much slower rate than long ago, but there is so much leftover gas available after the big bang that the universe will keep making stars and planets for a very long time to come.

A billion Earth-sized worlds

Based on the survey, scientists predict that there should already be 1 billion Earth-sized worlds in the Milky Way galaxy. That estimate skyrockets when you include the other 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe.

Kepler’s planet survey indicates that Earth-sized planets in a star’s habitable zone — the perfect distance that could allow water to pool on the surface — are ubiquitous in our galaxy. This leaves plenty of opportunity for untold more Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone to arise in the future — the last star isn’t expected to burn out until 100 trillion years from now.

The researchers say that future Earths are more likely to appear inside giant galaxy clusters and also in dwarf galaxies, which have yet to use up all their gas for building stars and accompanying planetary systems. By contrast, our Milky Way galaxy has used up much more of the gas available for future star formation.

A big advantage to our civilization arising early in the evolution of the universe is our being able to use powerful telescopes like Hubble to trace our lineage from the big bang through the early evolution of galaxies.

Regrettably, the observational evidence for the big bang and cosmic evolution, encoded in light and other electromagnetic radiation, will be all but erased away 1 trillion years from now, due to the runaway expansion of space. Any far-future civilizations that might arise will be largely clueless as to how or if the universe began and evolved.

Abstract of On The History and Future of Cosmic Planet Formation

We combine constraints on galaxy formation histories with planet formation models, yielding the Earth-like and giant planet formation histories of the Milky Way and the Universe as a whole. In the Hubble volume (1013 Mpc3), we expect there to be ∼1020 Earth-like and ∼1020giant planets; our own galaxy is expected to host ∼109 and ∼1010 Earth-like and giant planets, respectively. Proposed metallicity thresholds for planet formation do not significantly affect these numbers. However, the metallicity dependence for giant planets results in later typical formation times and larger host galaxies than for Earth-like planets. The Solar system formed at the median age for existing giant planets in the Milky Way, and consistent with past estimates, formed after 80 per cent of Earth-like planets. However, if existing gas within virialized dark matter haloes continues to collapse and form stars and planets, the Universe will form over 10 times more planets than currently exist. We show that this would imply at least a 92 per cent chance that we are not the only civilization the Universe will ever have, independent of arguments involving the Drake equation.

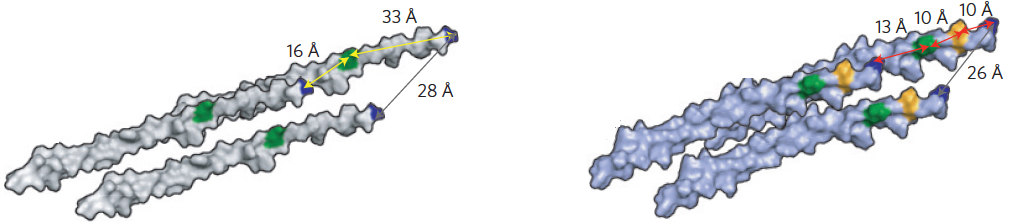

Abstract of Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon

Evidence for carbon cycling or biologic activity can be derived from carbon isotopes, because a high12C/13C ratio is characteristic of biogenic carbon due to the large isotopic fractionation associated with enzymatic carbon fixation. The earliest materials measured for carbon isotopes at 3.8 Ga are isotopically light, and thus potentially biogenic. Because Earth’s known rock record extends only to ∼4 Ga, earlier periods of history are accessible only through mineral grains deposited in later sediments. We report 12C/13C of graphite preserved in 4.1-Ga zircon. Its complete encasement in crack-free, undisturbed zircon demonstrates that it is not contamination from more recent geologic processes. Its 12C-rich isotopic signature may be evidence for the origin of life on Earth by 4.1 Ga.