HyperFrames taken with HyperCam predicted the relative ripeness of 10 different fruits with 94 percent accuracy, compared with only 62 percent for a typical RGB (visible light) camera (credit: University of Washington)

HyperCam, an affordable “hyperspectral” (sees beyond the visible range) camera technology being developed by the University of Washington and Microsoft Research, may enable consumers of the future to use a cell phone to tell which piece of fruit is perfectly ripe or if a work of art is genuine.

The technology uses both visible and invisible near-infrared light to “see” beneath surfaces and capture unseen details. This type of camera, typically used in industrial applications, can cost between several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars.

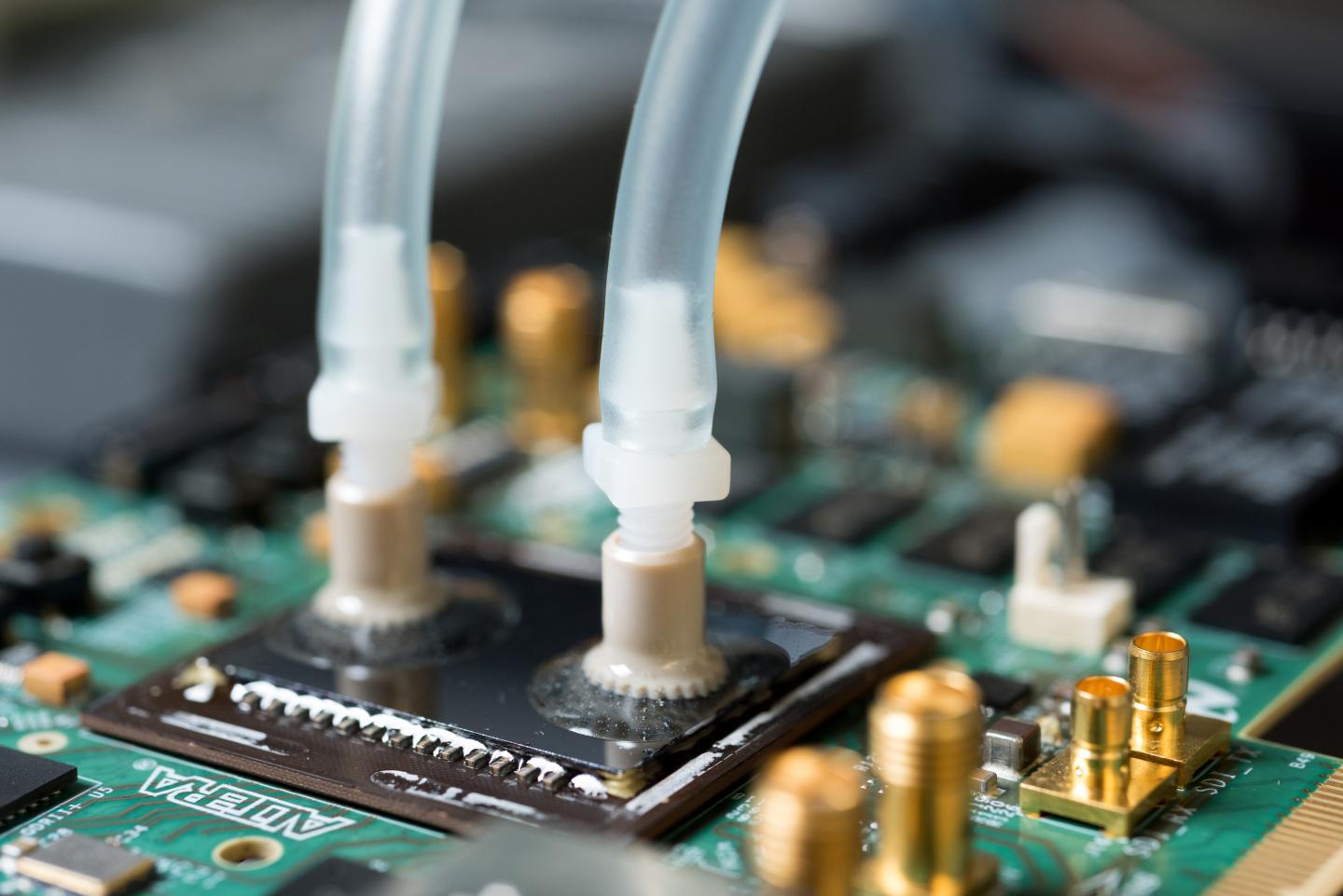

In a paper presented at the UbiComp 2015 conference, the team detailed a hardware solution that costs roughly $800, or potentially as little as $50 to add to a mobile phone camera. It illuminates a scene with 17 different wavelengths and generates an image for each. They also developed intelligent software that easily finds “hidden” differences between what the hyperspectral camera captures and what can be seen with the naked eye.

In one test, the team took hyperspectral images of 10 different fruits, from strawberries to mangoes to avocados, over the course of a week. The HyperCam images predicted the relative ripeness of the fruits with 94 percent accuracy, compared with only 62 percent for a typical camera.

The HyperCam system was also able differentiate between hand images of users with 99 percent accuracy. That can aid in everything from gesture recognition to biometrics to distinguishing between two different people playing the same video game.

“It’s not there yet, but the way this hardware was built you can probably imagine putting it in a mobile phone,” said Shwetak Patel, Washington Research Foundation Endowed Professor of Computer Science & Engineering and Electrical Engineering at the UW.

Compared to an image taken with a normal camera (left), HyperCam images (right) reveal detailed vein and skin texture patterns that are unique to each individual (credit: University of Washington)

How it works

Hyperspectral imaging is used today in everything from satellite imaging and energy monitoring to infrastructure and food safety inspections, but the technology’s high cost has limited its use to industrial or commercial purposes. Near-infrared cameras, for instance, can reveal whether crops are healthy. Thermal infrared cameras can visualize where heat is escaping from leaky windows or an overloaded electrical circuit.

HyperCam is a low-cost hyperspectral camera developed by UW and Microsoft Research that reveals details that are difficult or impossible to see with the naked eye (credit: University of Washington)

One challenge in hyperspectral imaging is sorting through the sheer volume of frames produced. The UW software analyzes the images and finds ones that are most different from what the naked eye sees, essentially zeroing in on ones that the user is likely to find most revealing.

“It mines all the different possible images and compares it to what a normal camera or the human eye will see and tries to figure out what scenes look most different,” Goel said.

“Next research steps will include making it work better in bright light and making the camera small enough to be incorporated into mobile phones and other devices,” he said.

Mayank Goel | HyperCam: HyperSpectral Imaging for Ubiquitous Computing Applications

Abstract of HyperCam: hyperspectral imaging for ubiquitous computing applications

Emerging uses of imaging technology for consumers cover a wide range of application areas from health to interaction techniques; however, typical cameras primarily transduce light from the visible spectrum into only three overlapping components of the spectrum: red, blue, and green. In contrast, hyperspectral imaging breaks down the electromagnetic spectrum into more narrow components and expands coverage beyond the visible spectrum. While hyperspectral imaging has proven useful as an industrial technology, its use as a sensing approach has been fragmented and largely neglected by the UbiComp community. We explore an approach to make hyperspectral imaging easier and bring it closer to the end-users. HyperCam provides a low-cost implementation of a multispectral camera and a software approach that automatically analyzes the scene and provides a user with an optimal set of images that try to capture the salient information of the scene. We present a number of use-cases that demonstrate HyperCam’s usefulness and effectiveness.