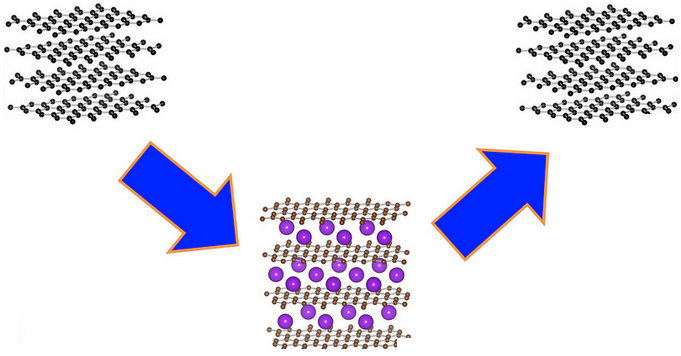

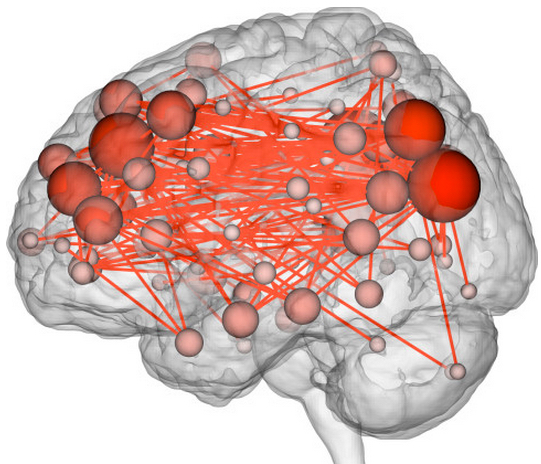

A connectome maps connections between different brain networks. (credit: Emily Finn)

Your brain activity appears to be as unique as your fingerprints, a new Yale-led “connectome fingerprinting” study published Monday (Oct. 12) in the journal Nature Neuroscience has found.

By analyzing* “connectivity profiles” (coordinated activity between pairs of brain regions) of fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) images from 126 subjects, the Yale researchers were able to identify specific individuals from the fMRI data alone by their identifying “fingerprint.” The researchers could also assess the subjects’ “fluid intelligence.”

“In most past studies, data have been used to draw contrasts between, say, patients and healthy controls,” said Emily Finn, a Ph.D. student in neuroscience and co-first author of the paper. “We have learned a lot from these sorts of studies, but they tend to obscure individual differences, which may be important.”

Two frontoparietal networks networks — the medial frontal (purple) and the frontoparietal (teal) — out of the 268 brain regions were found best for identifying people and predicting fluid intelligence (credit: Emily S Finn/Xilin Shen, CC BY-ND)

The researchers looked specifically at areas that showed synchronized activity. The characteristic connectivity patterns were distributed throughout the brain, but notably, two frontoparietal networks emerged as most distinctive.

“These networks are comprised of higher-order association cortices rather than primary sensory regions; these cortical regions are also the most evolutionarily recent and show the highest inter-subject variance,” the researchers note in their paper. “These networks tend to act as flexible hubs, switching connectivity patterns according to task demands. Additionally, broadly distributed across-network connectivity has been reported in these same regions, suggesting a role in large-scale coordination of brain activity.”

Notably, the researchers were able to match the scan of a given individual’s brain activity during one imaging session to that person’s brain scan at another time — even when a person was engaged in a different task in each session, although in that case, the predictive accuracy dropped from 98–99% accuracy to 80–90%.

Predicting and treating neuropsychiatric illnesses (or criminal behavior?)

Finn said she hopes that this ability might one day help clinicians predict or even treat neuropsychiatric diseases based on individual brain connectivity profiles. The paper notes that “aberrant functional connectivity in the frontoparietal networks has been linked to a variety of neuropsychiatric illnesses.”

The study raises troubling questions. “Richard Haier, an intelligence researcher at the University of California, Irvine, [suggests that ] schools could scan children to see what sort of educational environment they’d thrive in, or determine who’s more prone to addiction, or screen prison inmates to figure out whether they’re violent or not,” Wired reports.

“Minority Report” Hawk-eye display (credit: Fox)

Or perhaps identify future criminals — or even predict future crimes, as in “Hawk-eye” technology (portrayed in Minority Report episode 3).

Identifying fluid intelligence

The researchers also discovered that the same two frontoparietal networks were most predictive of the level of fluid intelligence (the capacity for on-the-spot reasoning to discern patterns and solve problems, independent of acquired knowledge) shown on intelligence tests. That’s consistent with previous reports that structural and functional properties of these networks relate to intelligence.

Data for the study came from the Human Connectome Project led by the WU-Minn Consortium, which is funded by the 16 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutes and Centers that support the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research, and by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University. Primary funding for the Yale researchers was provided by the NIH.

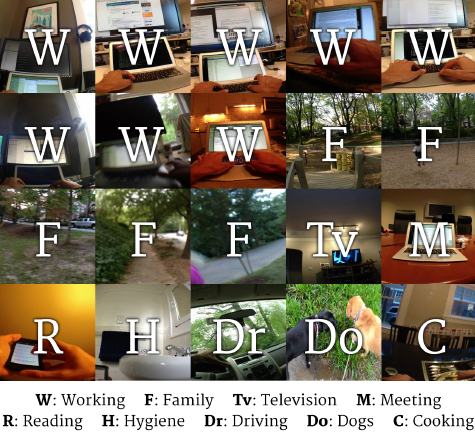

* Finn and co-first author Xilin Shen, under the direction of R. Todd Constable, professor of diagnostic radiology and neurosurgery at Yale, compiled fMRI data from 126 subjects who underwent six scan sessions over two days. Subjects performed different cognitive tasks during four of the sessions. In the other two, they simply rested. Researchers looked at activity in 268 brain regions: specifically, coordinated activity between pairs of regions. Highly coordinated activity implies two regions are functionally connected. Using the strength of these connections across the whole brain, the researchers were able to identify individuals from fMRI data alone, whether the subject was at rest or engaged in a task. They were also able to predict how subjects would perform on tasks.

Abstract of Functional connectome fingerprinting: identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies typically collapse data from many subjects, but brain functional organization varies between individuals. Here we establish that this individual variability is both robust and reliable, using data from the Human Connectome Project to demonstrate that functional connectivity profiles act as a ‘fingerprint’ that can accurately identify subjects from a large group. Identification was successful across scan sessions and even between task and rest conditions, indicating that an individual’s connectivity profile is intrinsic, and can be used to distinguish that individual regardless of how the brain is engaged during imaging. Characteristic connectivity patterns were distributed throughout the brain, but the frontoparietal network emerged as most distinctive. Furthermore, we show that connectivity profiles predict levels of fluid intelligence: the same networks that were most discriminating of individuals were also most predictive of cognitive behavior. Results indicate the potential to draw inferences about single subjects on the basis of functional connectivity fMRI.