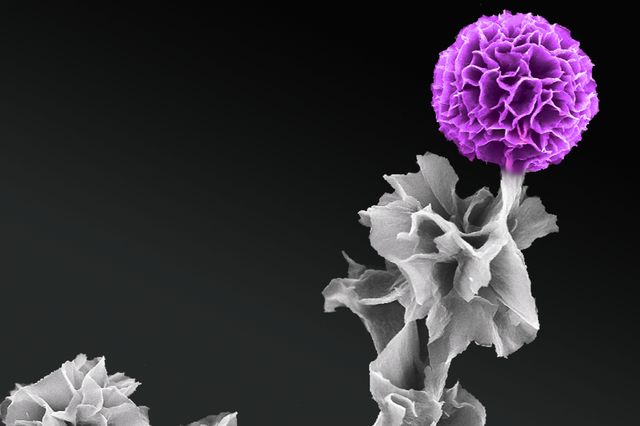

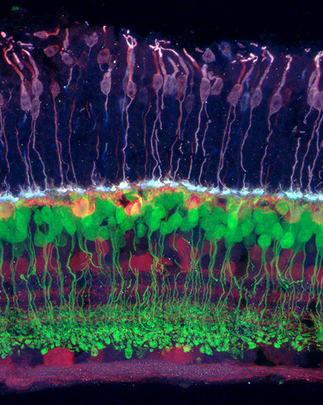

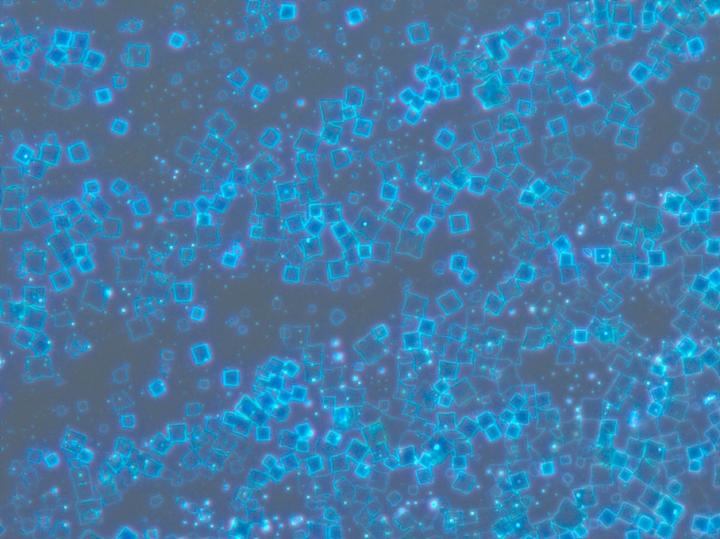

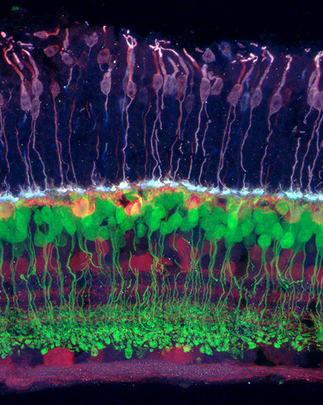

Scientists funded by the NIH BRAIN Initiative hope to diagram all of the circuits in the brain. One group will attempt to identify all of the connections among the retina’s ganglion cells (red), which transmit visual information from bipolar cells (green) and photoreceptors (purple) to the brain. (credit: Josh Morgan, Ph.D. and Rachel Wong, Ph.D./University of Washington)

The National Institutes of Health and the Kavli Foundation separately announced today (Oct. 1, 2015) commitments totaling $185 million in new funds supporting the BRAIN Initiative* — research aimed at deepening our understanding of the brain and brain-related disorders, such as traumatic brain injuries (TBI), Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease.

The NIH announced today its second wave of grants to support the goals of the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative, bringing the total NIH investment to nearly $85 million in fiscal year 2015.

Sixty-seven new awards totaling more than $38 million will go to 131 investigators working at 125 institutions in the United States and eight other countries. These awards expand NIH’s efforts to develop new tools and technologies to understand neural circuit function and capture a dynamic view of the brain in action.

Projects include proposals to develop soft self-driving electrodes, ultrasound methods for measuring brain activity, and the use of deep brain stimulation to treat traumatic brain injuries.

NIH has also announced new funding opportunities.

Planning for the NIH component of the BRAIN initiative is guided by the long-term scientific plan, BRAIN 2025: A Scientific Vision, which details seven high priority research areas**.

Kavli Foundation and university partners commit $100 million to brain research

The Kavli Foundation and its university partners also announced today the commitment of more than $100 million in new funds to enable research that moves forward the BRAIN Initiative.

The majority of the funds will establish three new Kavli neuroscience institutes at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU), The Rockefeller University, and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Each of the Institutes will receive a $20 million endowment supported equally by their universities and the Foundation, along with start-up funding. The three institutes will be joining an international network of seven Kavli Institutes carrying out fundamental research in neuroscience, and a broader network of 20 Kavli Institutes dedicated to astrophysics, nanoscience, neuroscience and theoretical physics.

The Foundation is also partnering with four other universities to build their Kavli Institute endowments further: at Columbia University; the University of California, San Diego; Yale University; and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

BRAIN Initiative event

A BRAIN Initiative event will be held October 20, 2015 at the Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting in Chicago, featuring an interactive panel discussion/Q&A session with updates on activities and opportunities offered by the BRAIN Initiative. Representatives from federal agencies, private research foundations, and universities will be present.

* In 2014, President Obama launched the BRAIN Initiative as a large-scale effort to equip researchers with fundamental insights necessary for treating a wide variety of brain disorders like Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, autism, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injury, with $46 million funding. These new tools and this deeper understanding will ultimately catalyze new treatments and cures for devastating brain disorders and diseases that are estimated by the World Health Organization to affect more than one billion people worldwide, according to NIH.

** From Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Working Group Report to the Advisory Committee to the Director, NIH:

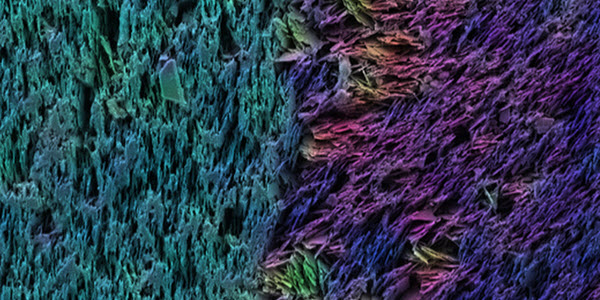

#1. Discovering diversity: Identify and provide experimental access to the different brain cell types to determine their roles in health and disease. It is within reach to characterize all cell types in the nervous system, and to develop tools to record, mark, and manipulate these precisely defined neurons in the living brain. We envision an integrated, systematic census of neuronal and glial cell types, and new genetic and non-genetic tools to deliver genes, proteins, and chemicals to cells of interest in non-human animals and in humans.

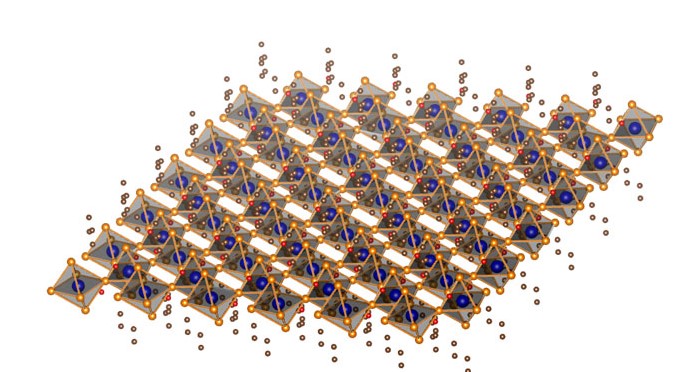

#2. Maps at multiple scales: Generate circuit diagrams that vary in resolution from synapses to the whole brain. It is increasingly possible to map connected neurons in local circuits and distributed brain systems, enabling an understanding of the relationship between neuronal structure and function. We envision improved technologies—faster, less expensive, scalable—for anatomic reconstruction of neural circuits at all scales, from non-invasive whole human brain imaging to dense reconstruction of synaptic inputs and outputs at the subcellular level.

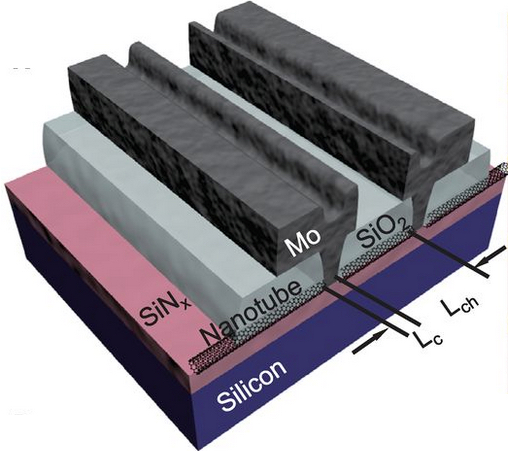

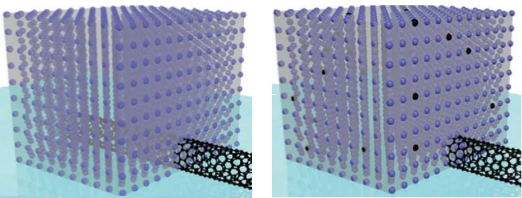

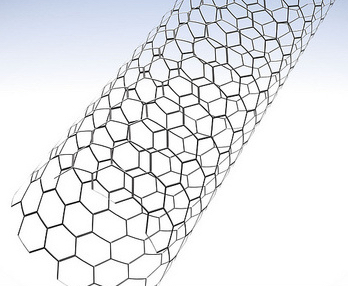

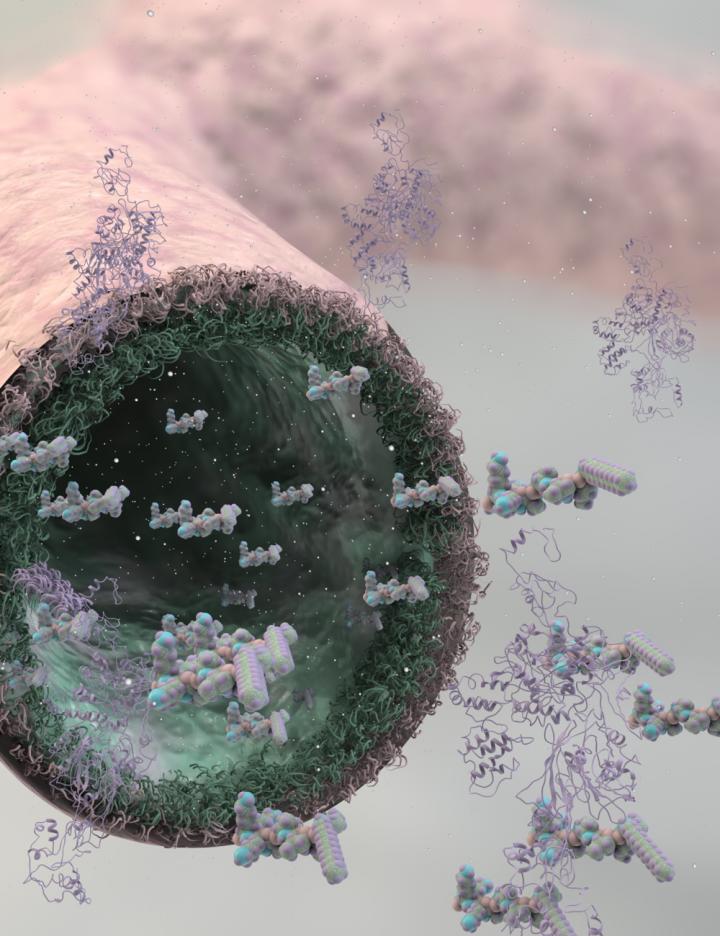

#3. The brain in action: Produce a dynamic picture of the functioning brain by developing and applying improved methods for large-scale monitoring of neural activity. We should seize the challenge of recording dynamic neuronal activity from complete neural networks, over long periods, in all areas of the brain. There are promising opportunities both for improving existing technologies and for developing entirely new technologies for neuronal recording, including methods based on electrodes, optics, molecular genetics, and nanoscience, and encompassing different facets of brain activity.

#4. Demonstrating causality: Link brain activity to behavior with precise interventional tools that change neural circuit dynamics. By directly activating and inhibiting populations of neurons, neuroscience is progressing from observation to causation, and much more is possible. To enable the immense potential of circuit manipulation, a new generation of tools for optogenetics, chemogenetics, and biochemical and electromagnetic modulation should be developed for use in animals and eventually in human patients.

#5. Identifying fundamental principles: Produce conceptual foundations for understanding the biological basis of mental processes through development of new theoretical and data analysis tools. Rigorous theory, modeling, and statistics are advancing our understanding of complex, nonlinear brain functions where human intuition fails. New kinds of data are accruing at increasing rates, mandating new methods of data analysis and interpretation. To enable progress in theory and data analysis, we must foster collaborations between experimentalists and scientists from statistics, physics, mathematics, engineering, and computer science.

#6. Advancing human neuroscience: Develop innovative technologies to understand the human brain and treat its disorders; create and support integrated human brain research networks. Consenting humans who are undergoing diagnostic brain monitoring, or receiving neurotechnology for clinical applications, provide an extraordinary opportunity for scientific research. This setting enables research on human brain function, the mechanisms of human brain disorders, the effect of therapy, and the value of diagnostics. Meeting this opportunity requires closely integrated research teams performing according to the highest ethical standards of clinical care and research. New mechanisms are needed to maximize the collection of this priceless information and ensure that it benefits people with brain disorders.

#7. From BRAIN Initiative to the brain: Integrate new technological and conceptual approaches produced in Goals #1-6 to discover how dynamic patterns of neural activity are transformed into cognition, emotion, perception, and action in health and disease. The most important outcome of the BRAIN Initiative will be a comprehensive, mechanistic understanding of mental function that emerges from synergistic application of the new technologies and conceptual structures developed under the BRAIN Initiative.

The overarching vision of the BRAIN Initiative is best captured by Goal #7—combining these approaches into a single, integrated science of cells, circuits, brain, and behavior. For example, immense value is added if recordings are conducted from identified cell types whose anatomical connections are established in the same study. Such an experiment is currently an exceptional tour de force; with new technology, it could become routine. In another example, neuronal populations recorded during complex behavior might be immediately retested with circuit manipulation techniques to determine their causal role in generating the behavior. Theory and modeling should be woven into successive stages of ongoing experiments, enabling bridges to be built from single cells to connectivity, population dynamics, and behavior.