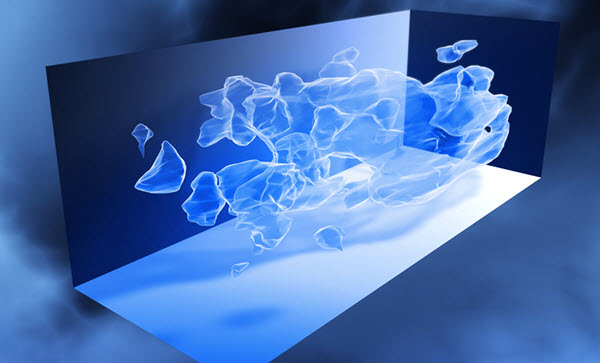

This 3D map illustrates the large-scale distribution of dark matter, reconstructed from measurements of weak gravitational lensing by using the Hubble Space Telescope (credit: image courtesy of DOE/Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory)

A new theory that may explain why dark matter has evaded direct detection in Earth-based experiments has been developed by team of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) particle physicists known as the Lattice Strong Dynamics Collaboration.

The group has combined theoretical and computational physics techniques and used the Laboratory’s massively parallel 2-petaflop Vulcan supercomputer to devise a new model of dark matter. The model identifies today’s dark matter as naturally “stealthy.” But in the extremely high-temperature plasma conditions that pervaded the early universe, it would have been easy to see dark matter via interactions with ordinary matter, the model shows.

A balancing act in the early universe

“These interactions in the early universe are important because ordinary and dark matter abundances today are strikingly similar in size, suggesting this occurred because of a balancing act performed between the two before the universe cooled,” said Pavlos Vranas of LLNL, one of the authors of a paper in an upcoming edition of the journal Physical Review Letters.

Dark matter makes up 83 percent of all matter in the universe and does not interact directly with electromagnetic or strong and weak nuclear forces. Light does not bounce off of it, and ordinary matter goes through it with only the feeblest of interactions. It is essentially invisible, yet its interactions with gravity produce striking effects on the movement of galaxies and galactic clusters, leaving little doubt of its existence.

The key to stealth dark matter’s split personality is its compositeness and the miracle of confinement. Like quarks in a neutron, at high temperatures these electrically charged constituents interact with nearly everything. But at lower temperatures, they bind together to form an electrically neutral composite particle. Unlike a neutron, which is bound by the ordinary strong interaction of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the stealthy neutron would have to be bound by a new and yet-unobserved strong interaction, a dark form of QCD.

CERN experiments may test the stealth dark matter theory

“It is remarkable that a dark matter candidate just several hundred times heavier than the proton could be a composite of electrically charged constituents and yet have evaded direct detection so far,” Vranas said.

Similar to protons, stealth dark matter is stable and does not decay over cosmic times. However, like QCD, it produces a large number of other nuclear particles that decay shortly after their creation. These particles can have net electric charge but would have decayed away a long time ago. In a particle collider with sufficiently high energy (such as the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland), these particles can be produced again for the first time since the early universe. They could generate unique signatures in the particle detectors because they could be electrically charged.

“Underground direct detection experiments or experiments at the Large Hadron Collider may soon find evidence of (or rule out) this new stealth dark matter theory,” Vranas said.

Other collaborators include researchers from Yale University, Boston University, Institute for Nuclear Theory, Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, University of California, Davis, University of Oregon, University of Colorado, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and Syracuse University. The DOE Office of Science High Energy Theory and the High Energy Physics Lattice SciDAC program supported this research.

Abstract of Direct Detection of Stealth Dark Matter through Electromagnetic Polarizability

We calculate the spin-independent scattering cross section for direct detection that results from the electromagnetic polarizability of a composite scalar baryon dark matter candidate — “Stealth Dark Matter”, that is based on a dark SU(4) confining gauge theory. In the nonrelativistic limit, electromagnetic polarizability proceeds through a dimension-7 interaction leading to a very small scattering cross section for dark matter with weak scale masses. This represents a lower bound on the scattering cross section for composite dark matter theories with electromagnetically charged constituents. We carry out lattice calculations of the polarizability for the lightest baryons in SU(3) and SU(4) gauge theories using the background field method on quenched configurations. We find the polarizabilities of SU(3) and SU(4) to be comparable (within about 50%) normalized to the baryon mass, which is suggestive for extensions to larger SU(N) groups. The resulting scattering cross sections with a xenon target are shown to be potentially detectable in the dark matter mass range of about 200-700 GeV, where the lower bound is from the existing LUX constraint while the upper bound is the coherent neutrino background. Significant uncertainties in the cross section remain due to the more complicated interaction of the polarizablity operator with nuclear structure, however the steep dependence on the dark matter mass, 1/m_B^6, suggests the observable dark matter mass range is not appreciably modified. We briefly highlight collider searches for the mesons in the theory as well as the indirect astrophysical effects that may also provide excellent probes of stealth dark matter.