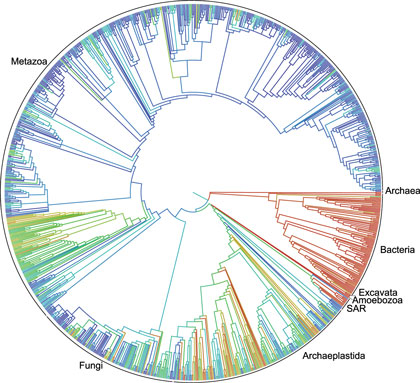

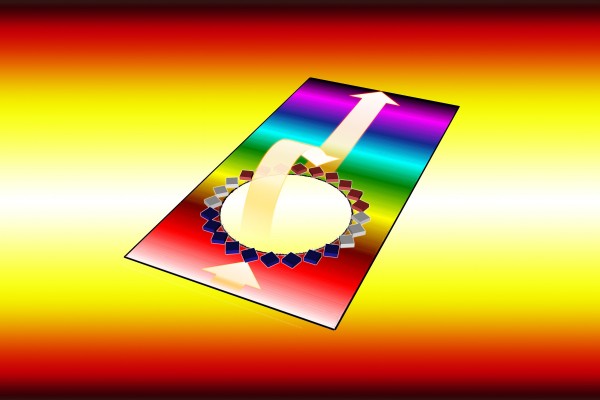

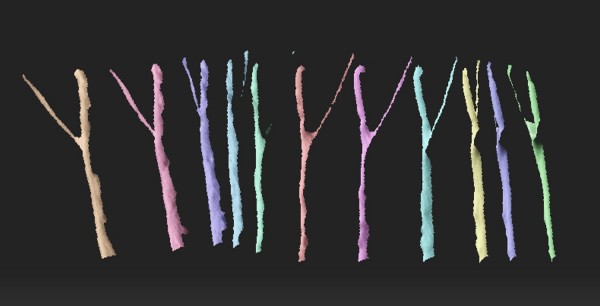

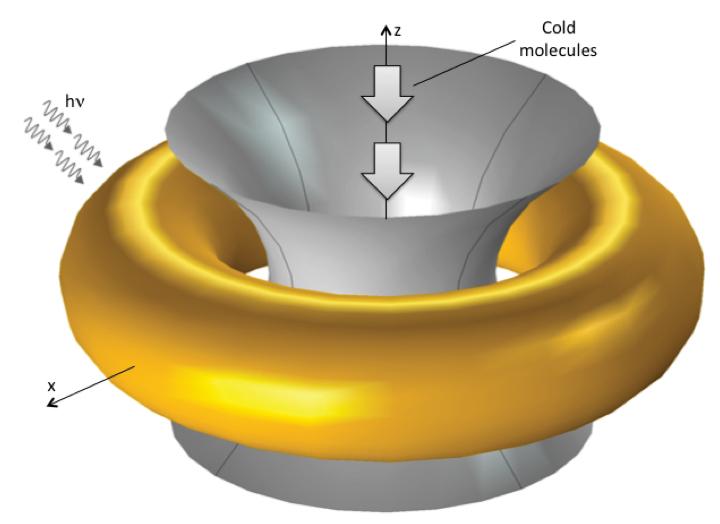

With a nano-ring-based toroidal trap, cold polar molecules near the gray shaded surface approaching the central region may be trapped within a nanometer-scale volume (credit: ORNL)

In a paper published in Physical Review A, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and University of Tennessee physicists describe conceptually how they may be able to trap and exploit a molecule’s energy to advance a number of fields.

“A single molecule has many degrees of freedom, or ways of expressing its energy and dynamics, including vibrations, rotations and translations,” said Ali Passian of Oak Ridge National Lab. “For years, physicists have searched for ways to take advantage of these molecular states, including how they could be used in high-precision instruments or as an information storage device for applications such as quantum computing.”

It’s a trap!

Catching a molecule with minimal disturbance is not an easy task, considering its size — about 1 nanometer — but this paper proposes a method that may overcome that obstacle.

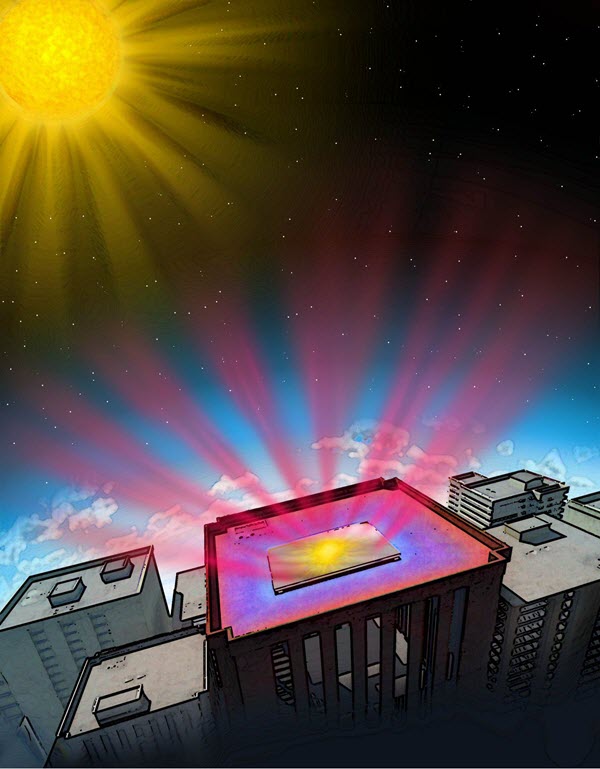

When interacting with laser light, the ring toroidal nanostructure can trap the slower molecules at its center. That’s because the nano-trap, which can be made of gold using conventional nanofabrication techniques, creates a highly localized force field surrounding the molecules. The team envisions using scanning probe microscopy techniques, which can measure extremely small forces, to access individual nano-traps.

“Once trapped, we can interrogate the molecules for their spectroscopic and electromagnetic properties and study them in isolation without disturbance from the neighboring molecules,” Passian said.

Previous demonstrations of trapping molecules have relied on large systems to confine charged particles such as single ions. Next, the researchers plan to build actual nanotraps and conduct experiments to determine the feasibility of fabricating a large number of traps on a single chip.

“If successful, these experiments could help enable information storage and processing devices that greatly exceed what we have today, thus bringing us closer to the realization of quantum computers,” Passian said.

Abstract of Toroidal nanotraps for cold polar molecules

Electronic excitations in metallic nanoparticles in the optical regime that have been of great importance in surface-enhanced spectroscopy and emerging applications of molecular plasmonics, due to control and confinement of electromagnetic energy, may also be of potential to control the motion of nanoparticles and molecules. Here, we propose a concept for trapping polarizable particles and molecules using toroidal metallic nanoparticles. Specifically, gold nanorings are investigated for their scattering properties and field distribution to computationally show that the response of these optically resonant particles to incident photons permit the formation of a nanoscale trap when proper aspect ratio, photon wavelength, and polarization are considered. However, interestingly the resonant plasmonic response of the nanoring is shown to be detrimental to the trap formation. The results are in good agreement with analytic calculations in the quasistatic limit within the first-order perturbation of the scalar electric potential. The possibility of extending the single nanoring trapping properties to two-dimensional arrays of nanorings is suggested by obtaining the field distribution of nanoring dimers and trimers.