Two recently published studies in the journals Age and the British Journal of Nutrition (BJN) demonstrate that consuming cocoa flavanols improves cardiovascular function and lessens the burden on the heart that comes with the aging and stiffening of arteries, while reducing the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD)

As we age, our blood vessels become less flexible and less able to expand to let blood flow and circulate normally, and the risk of hypertension also increases. Arterial stiffness and blood vessel dysfunction are linked with cardiovascular disease — the number one cause of deaths worldwide.

Cocoa flavanols increase blood vessel flexibility and lower blood pressure

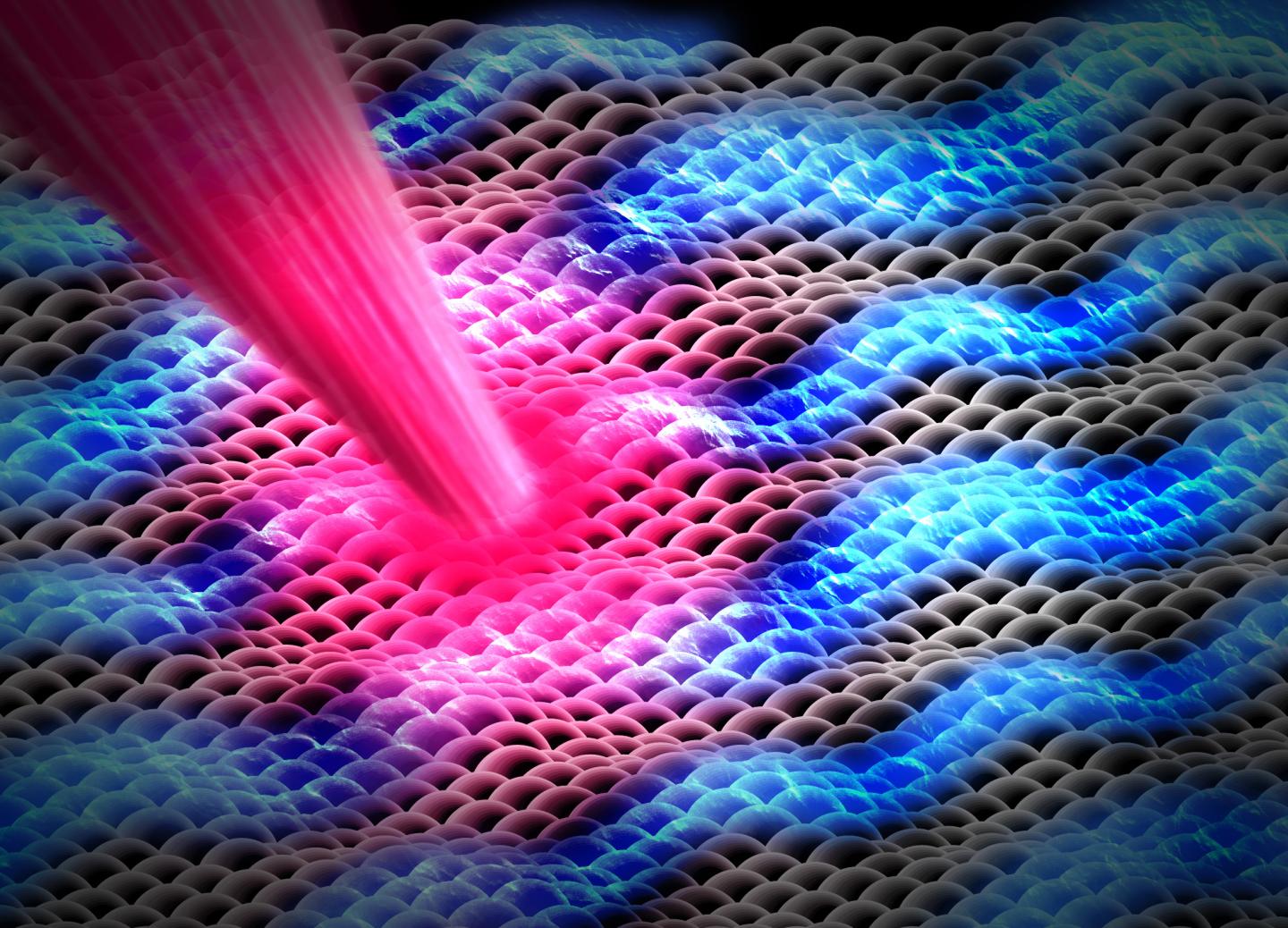

Cocoa pods (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Cocoa flavanols are plant-derived bioactives from the cacao bean. Dietary intake of flavanols has been shown to have a beneficial effect on cardiovascular health, but the compounds are often destroyed during normal food processing.

Earlier studies have demonstrated that cocoa flavanol intake improves the elasticity of blood vessels and lowers blood pressure.

But, for the most part, these investigations have focused on high-risk individuals like smokers and people that have already been diagnosed with conditions like hypertension and coronary heart disease.

These two studies are the first to look at the different effects dietary cocoa flavanols can have on the blood vessels of healthy, low-risk individuals with no signs or symptoms of cardiovascular disease.

In the study* published in Age, they found that vasodilation was significantly improved in both age groups that consumed flavanols over the course of the study (by 33% in the younger age group and 32% in the older age group over the control intervention).

In the older age group, a statistically and clinically significant decrease in systolic blood pressure of 4 mmHg over control was also seen.

Improving cardiovascular health and lowering the risk of CVD

In the second study**, published in BJN, the researchers extended their investigations to a larger group (100) of healthy middle-aged men and women (35–60 years) with low risk of CVD.

“We found that intake of flavanols significantly improves several of the hallmarks of cardiovascular health,” says Professor Kelm. In particular, the researchers found that consuming flavanols for four weeks significantly increased flow-mediated vasodilation by 21%.

Increased flow-mediated vasodilation is a sign of improved endothelial function and has been shown by some studies to be associated with decreased risk of developing CVD. In addition, taking flavanols decreased blood pressure (systolic by 4.4 mmHg, diastolic by 3.9 mmHg), and improved the blood cholesterol profile by decreasing total cholesterol (by 0.2 mmol/L), decreasing LDL cholesterol (by 0.17 mmol/L), and increasing HDL cholesterol (by 0.1 mmol/L).

Data source: United Nations Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2014). World Population Ageing 2013 (credit: MARS Cocoa Health Science)

The researchers also calculated the Framingham Risk Score — a widely used model to estimate the 10-year cardiovascular risk of an individual — and found that flavanol intake reduced the risk of CVD. “Our results indicate that dietary flavanol intake reduces the 10-year risk of being diagnosed with CVD by 22% and the 10-year risk of suffering a heart attack by 31%,” says Professor Kelm.

The combined results of these studies demonstrate that flavanols are effective at mitigating age-related changes in blood vessels, and could thereby reduce the risk of CVD in healthy individuals.

The application of 10-year Framingham Risk Scores should be interpreted with caution as the duration of the BJN study was weeks not years and the number of participants was around 100, not reaching the scale of the Framingham studies.

Other longer-term studies, such as the 5-year COcoa Supplement and Multivitamin Outcomes Study (COSMOS) of 18,000 men and women, are now underway to investigate the health potential of flavanols on a much larger scale.

Poor diet and high blood pressure now number one risk factors for death

A related huge international study of global causes of death has revealed high blood pressure is the number one individual risk factor associated with Australian deaths, contributing to 28,500 deaths a year.

Smoking and high body mass index are number two and three respectively, while drug use is among the fastest growing risk factors for poor health in Australia, up 53 per cent between 1990 and 2013.

However, deaths from high cholesterol have decreased by 25 per cent, and deaths from diets low in fruit and vegetables have decreased by 10 per cent.

The finding is from a new analysis of global cause-of-death data by the University of Melbourne and the University of Washington published in The Lancet last week.

Researchers looked at 79 risk factors for death in 188 countries between 1990 and 2013.

The risk factors examined in the study contributed to almost 31 million deaths worldwide in 2013, up from 25 million deaths in 1990. The top risks associated with the deaths of both men and women in Australia are high blood pressure, smoking, high body mass index, and high fasting plasma glucose.

Top risk factors for the rest of the world include:

- In much of the Middle East and Latin America, high body mass index is the number-one risk associated with health loss.

- In South and Southeast Asia, household air pollution is a leading risk, and India also grapples with high risks of unsafe water and childhood under-nutrition.

- Alcohol is the number-two risk in Russia.

- Smoking is the number-one risk in many high-income countries, including the United Kingdom.

- The most marked differences are found in sub-Saharan Africa, which, unlike other regions, is dominated by a combination of childhood malnutrition, unsafe water and lack of sanitation, unsafe sex, and alcohol use.

- Wasting (low weight) accounts for one in five deaths of children under five-years-old, highlighting the importance of child malnutrition as a risk factor.

- Unsafe sex took a huge toll on global health, contributing to 82 per cent of HIV/AIDS deaths and 94 per cent of HIV/AIDS deaths among 15- to 19-year-olds in 2013. This has a greater impact on South Africa than any other country, 38 per cent of South African deaths were attributed to unsafe sex. The global burden of unsafe sex grew from 1990 and peaked in 2005.

The study included several risk factors in its analysis for the first time: wasting (low weight for a person’s height), stunting (low height for a person’s age), unsafe sex, HIV, no hand-washing with soap, intimate partner violence.

In Australia, increases in deaths due to high body mass index and diabetes-related illnesses have been increased 35 per cent and 47 per cent respectively. Australians are also grappling with poor kidney function and low physical activity, both of which are not among the top-10 global risk factors.

The leading risk factors associated with poor health in Australia in 2013 were high body mass index, smoking, and high blood pressure. While these were also in the top-five risk factors in 1990, smoking has decreased slightly, by 4 per cent.

Senior author on the study, University of Melbourne Professor Alan Lopez, said many of these risk factors for Australian deaths are preventable with lifestyle changes.

“While our study shows that public policy in Australia has been effective in reducing the health impacts of high cholesterol and insufficient fruit and vegetables in our diet, progress against some large, avoidable risks has been less impressive,” Prof Lopez said.

“Smoking, high blood pressure and obesity are still prevalent among adult Australians and remain a large cause of disease burden. We can, and ought, to be more conscientious in reducing these exposures among all Australians, not only those considered at high risk.”

The study was conducted by an international consortium of researchers working on the Global Burden of Disease project and led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington.

* Two groups of 22 young (<35 years of age) and 20 older (50-80 years of age) healthy men consumed either a flavanol-containing drink, or a flavanol-free control drink, twice a day for two weeks. The researchers then measured the effect of flavanols on hallmarks of cardiovascular aging, such as arterial stiffness (as measured by pulse wave velocity), blood pressure and flow-mediated vasodilation (the extent to which blood vessels dilate in response to nitric oxide).

** The participants were randomly and blindly assigned into groups that consumed either a flavanol-containing drink or a flavanol-free control drink, twice a day for four weeks. The researchers also measured cholesterol levels in the study groups, in addition to vasodilation, arterial stiffness and blood pressure.

Abstract of Cocoa flavanol intake improves endothelial function and Framingham Risk Score in healthy men and women: a randomised, controlled, double-masked trial: the Flaviola Health Study

Cocoa flavanol (CF) intake improves endothelial function in patients with cardiovascular risk factors and disease. We investigated the effects of CF on surrogate markers of cardiovascular health in low risk, healthy, middle-aged individuals without history, signs or symptoms of CVD. In a 1-month, open-label, one-armed pilot study, bi-daily ingestion of 450 mg of CF led to a time-dependent increase in endothelial function (measured as flow-mediated vasodilation (FMD)) that plateaued after 2 weeks. Subsequently, in a randomised, controlled, double-masked, parallel-group dietary intervention trial (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01799005), 100 healthy, middle-aged (35–60 years) men and women consumed either the CF-containing drink (450 mg) or a nutrient-matched CF-free control bi-daily for 1 month. The primary end point was FMD. Secondary end points included plasma lipids and blood pressure, thus enabling the calculation of Framingham Risk Scores and pulse wave velocity. At 1 month, CF increased FMD over control by 1·2 % (95 % CI 1·0, 1·4 %). CF decreased systolic and diastolic blood pressure by 4·4 mmHg (95 % CI 7·9, 0·9 mmHg) and 3·9 mmHg (95 % CI 6·7, 0·9 mmHg), pulse wave velocity by 0·4 m/s (95 % CI 0·8, 0·04 m/s), total cholesterol by 0·20 mmol/l (95 % CI 0·39, 0·01 mmol/l) and LDL-cholesterol by 0·17 mmol/l (95 % CI 0·32, 0·02 mmol/l), whereas HDL-cholesterol increased by 0·10 mmol/l (95 % CI 0·04, 0·17 mmol/l). By applying the Framingham Risk Score, CF predicted a significant lowering of 10-year risk for CHD, myocardial infarction, CVD, death from CHD and CVD. In healthy individuals, regular CF intake improved accredited cardiovascular surrogates of cardiovascular risk, demonstrating that dietary flavanols have the potential to maintain cardiovascular health even in low-risk subjects.

Abstract of Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013

Background: The Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factor study 2013 (GBD 2013) is the first of a series of annual updates of the GBD. Risk factor quantification, particularly of modifiable risk factors, can help to identify emerging threats to population health and opportunities for prevention. The GBD 2013 provides a timely opportunity to update the comparative risk assessment with new data for exposure, relative risks, and evidence on the appropriate counterfactual risk distribution.

Methods: Attributable deaths, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) have been estimated for 79 risks or clusters of risks using the GBD 2010 methods. Risk–outcome pairs meeting explicit evidence criteria were assessed for 188 countries for the period 1990–2013 by age and sex using three inputs: risk exposure, relative risks, and the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL). Risks are organised into a hierarchy with blocks of behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks at the first level of the hierarchy. The next level in the hierarchy includes nine clusters of related risks and two individual risks, with more detail provided at levels 3 and 4 of the hierarchy. Compared with GBD 2010, six new risk factors have been added: handwashing practices, occupational exposure to trichloroethylene, childhood wasting, childhood stunting, unsafe sex, and low glomerular filtration rate. For most risks, data for exposure were synthesised with a Bayesian meta-regression method, DisMod-MR 2.0, or spatial-temporal Gaussian process regression. Relative risks were based on meta-regressions of published cohort and intervention studies. Attributable burden for clusters of risks and all risks combined took into account evidence on the mediation of some risks such as high body-mass index (BMI) through other risks such as high systolic blood pressure and high cholesterol.

Findings: All risks combined account for 57·2% (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 55·8–58·5) of deaths and 41·6% (40·1–43·0) of DALYs. Risks quantified account for 87·9% (86·5–89·3) of cardiovascular disease DALYs, ranging to a low of 0% for neonatal disorders and neglected tropical diseases and malaria. In terms of global DALYs in 2013, six risks or clusters of risks each caused more than 5% of DALYs: dietary risks accounting for 11·3 million deaths and 241·4 million DALYs, high systolic blood pressure for 10·4 million deaths and 208·1 million DALYs, child and maternal malnutrition for 1·7 million deaths and 176·9 million DALYs, tobacco smoke for 6·1 million deaths and 143·5 million DALYs, air pollution for 5·5 million deaths and 141·5 million DALYs, and high BMI for 4·4 million deaths and 134·0 million DALYs. Risk factor patterns vary across regions and countries and with time. In sub-Saharan Africa, the leading risk factors are child and maternal malnutrition, unsafe sex, and unsafe water, sanitation, and handwashing. In women, in nearly all countries in the Americas, north Africa, and the Middle East, and in many other high-income countries, high BMI is the leading risk factor, with high systolic blood pressure as the leading risk in most of Central and Eastern Europe and south and east Asia. For men, high systolic blood pressure or tobacco use are the leading risks in nearly all high-income countries, in north Africa and the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. For men and women, unsafe sex is the leading risk in a corridor from Kenya to South Africa.

Interpretation: Behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks can explain half of global mortality and more than one-third of global DALYs providing many opportunities for prevention. Of the larger risks, the attributable burden of high BMI has increased in the past 23 years. In view of the prominence of behavioural risk factors, behavioural and social science research on interventions for these risks should be strengthened. Many prevention and primary care policy options are available now to act on key risks.

Funding: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.