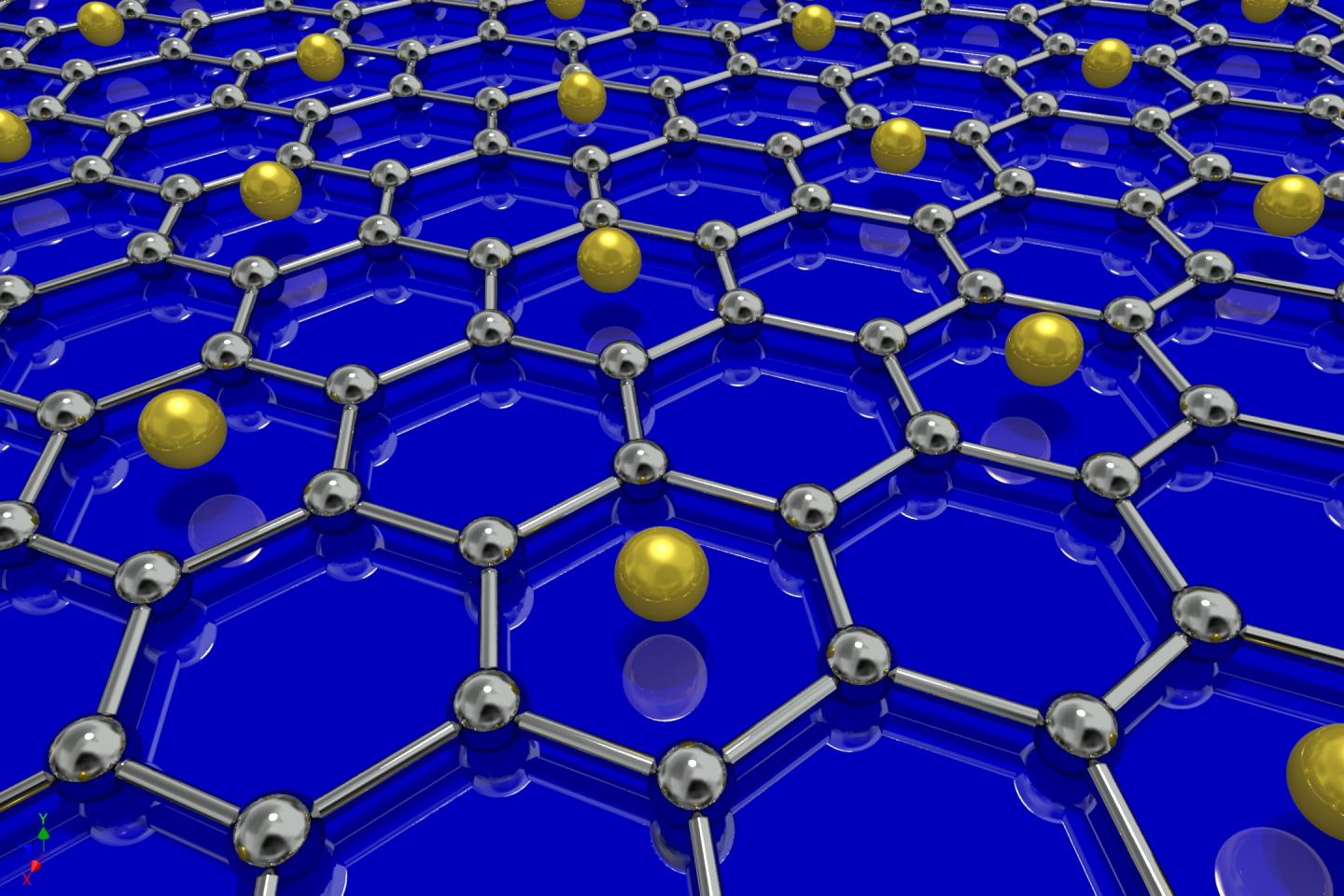

Atomic force micrograph of complementary single-wall carbon nanotubes in thin-film-transistor channel (credit: Michael L. Geier et al./Nature Nanotechnology)

Northwestern University engineers say that have finally found the key to practical use of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) in integrated circuits. Individual transistors made from CNTs are faster and more energy-efficient and reliable than those made from other materials.

The problem. But making the leap to wafer-scale integrated circuits (a microprocessor typically has a billion transistors) is a challenge. The process is incredibly expensive, often requiring billion-dollar cleanrooms to keep the delicate nano-sized components safe from the potentially damaging effects of air, water, and dust.

And researchers have struggled to create a carbon nanotube-based integrated circuit in which the transistors are spatially uniform across the material, which is needed for the overall system to work.

The solution. Now Hersam and his team have found a key to solving all these issues: newly developed encapsulation layers that protect carbon nanotubes from environmental degradation.

Dealing with environmental degradation

“One of the realities of a nanomaterial, such as a carbon nanotube, is that essentially all of its atoms are on the surface,” explained Northwestern Engineering’s Mark Hersam, the Walter P. Murphy Professor of Materials Science and Engineering. “So anything that touches the surface of these materials can influence their properties.

“If we made a series of transistors and left them out in the air, water and oxygen would stick to the surface of the nanotubes, degrading them over time. We thought that adding a protective encapsulation layer could arrest this degradation process to achieve substantially longer lifetimes.”*

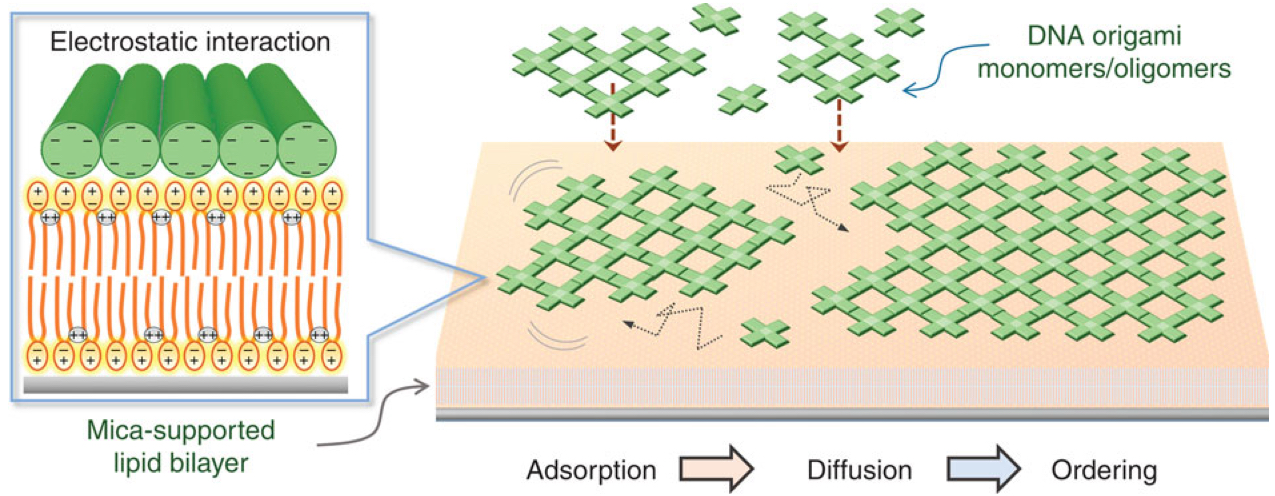

To demonstrate proof of concept, Hersam developed nanotube-based static random-access memory (SRAM) circuits. SRAM is a key component of all microprocessors, often making up as much as 85 percent of the transistors in the central-processing unit in a common computer. To create the encapsulated carbon nanotubes, the team first deposited the carbon nanotubes from a solution previously developed in Hersam’s lab. Then they coated the tubes with their encapsulation layers.

Functional CNT-based SRAM memory circuits

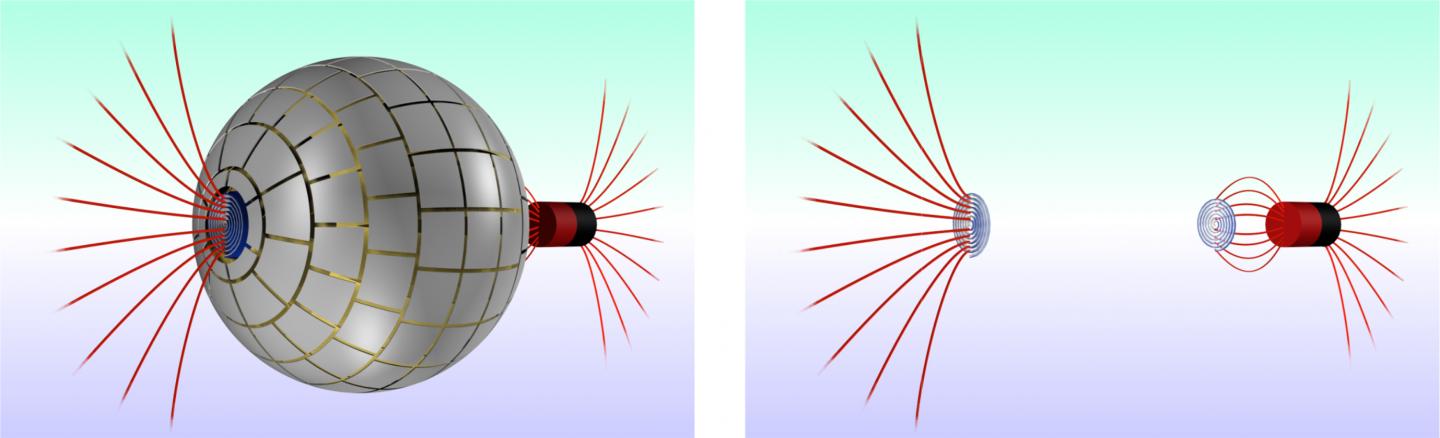

Complementary single-wall carbon nanotube thin-film-transistor (SWCNT TFT) structures. (A) Optical micrographs of the fabricated device with channel width of 150 μm and length of 50 μm (inset) and an array of SWCNT TFTs (scale bar: 1 mm). (B) Schematic cross-section of a SWCNT TFT. (C) Atomic force micrograph of the SWCNTs in the TFT channel with a linear density of ~10 SWCNTs/μm (Height color bar: 0 to 15 nm). (credit: Michael L. Geier et al./Nature Nanotechnology)

Using the encapsulated carbon nanotubes, Hersam’s team successfully designed and fabricated arrays of working SRAM circuits. Not only did the encapsulation layers protect the sensitive device from the environment, but they improved spatial uniformity among individual transistors across the wafer. While Hersam’s integrated circuits demonstrated a long lifetime, transistors that were deposited from the same solution but not coated degraded within hours.

“After we’ve made the devices, we can leave them out in air with no further precautions,” Hersam said. “We don’t need to put them in a vacuum chamber or controlled environment. Other researchers have made similar devices but immediately had to put them in a vacuum chamber or inert environment to keep them stable. That’s obviously not going to work in a real-world situation.”

Implications for portable/wearable electronics

These features, when combined with recent advances in flexible and printed electronics have potentially wide-ranging implications for high-performance portable and wearable electronics, the researchers suggest in the paper.

Flexible carbon nanotube-based transistors could replace rigid silicon to enable wearable electronics, Hersam says. The cheaper manufacturing method also opens doors for smart cards — credit cards embedded with personal information to reduce the likelihood of fraud.

“Smart cards are only realistic if they can be realized using extremely low-cost manufacturing,” he said. “Because our solution-processed carbon nanotubes are compatible with scalable and inexpensive printing methods, our results could enable smart cards and related printed electronics applications.”

The research appeared online in Nature Nanotechology on September 7. It was supported by the Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation.

* Hersam compares his solution to one currently used for organic light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which experienced similar problems after they were first realized. Many people assumed that organic LEDs would have no future because they degraded in air. After researchers developed an encapsulation layer for the material, organic LEDs are now used in many commercial applications, including displays for smartphones, car radios, televisions, and digital cameras. Made from polymers and inorganic oxides, Hersam’s encapsulation layer is based on the same idea but tailored for carbon nanotubes.

Abstract of Solution-processed carbon nanotube thin-film complementary static random access memory

Over the past two decades, extensive research on single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) has elucidated their many extraordinary properties, making them one of the most promising candidates for solution-processable, high-performance integrated circuits. In particular, advances in the enrichment of high-purity semiconducting SWCNTs have enabled recent circuit demonstrations including synchronous digital logic, flexible electronics and high-frequency applications. However, due to the stringent requirements of the transistors used in complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) logic as well as the absence of sufficiently stable and spatially homogeneous SWCNT thin-film transistors, the development of large-scale SWCNT CMOS integrated circuits has been limited in both complexity and functionality. Here, we demonstrate the stable and uniform electronic performance of complementary p-type and n-type SWCNT thin-film transistors by controlling adsorbed atmospheric dopants and incorporating robust encapsulation layers. Based on these complementary SWCNT thin-film transistors, we simulate, design and fabricate arrays of low-power static random access memory circuits, achieving large-scale integration for the first time based on solution-processed semiconductors.