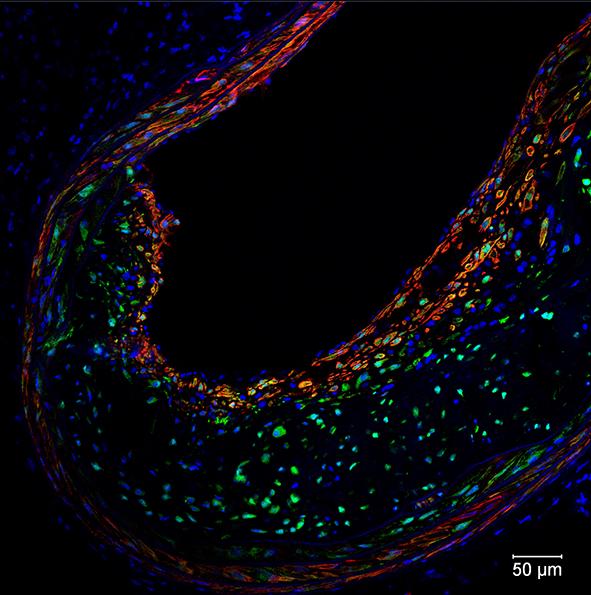

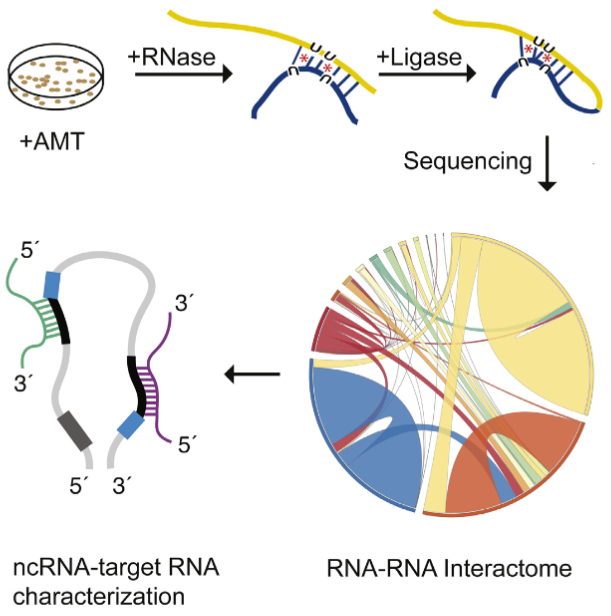

The LIGR-seq method for global-scale mapping of RNA-RNA interactions in vivo to reveal unexpected functions for uncharacterized RNAs that act via base-pairing interactions (credit: University of Toronto)

What used to be dismissed by many as “junk DNA” has now become vitally important, as accelerating genomic data points to the importance of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) — a genome’s messages that do not specifically code for proteins — in development and disease.

But our progress in understanding these molecules has been slow because of the lack of technologies that allow for systematic mapping of their functions.

Now, professor Benjamin Blencowe’s team at the University of Toronto’s Donnelly Centre has developed a method called “LIGR-seq” that enables scientists to explore in depth what ncRNAs do in human cells.

The study, described in Molecular Cell, was published on May 19, along with two other papers, in Molecular Cell and Cell, respectively, from Yue Wan’s group at the Genome Institute of Singapore and Howard Chang’s group at Stanford University in California, who developed similar methods to study RNAs in different organisms.

So what exactly do ncRNAs do?

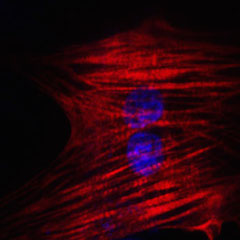

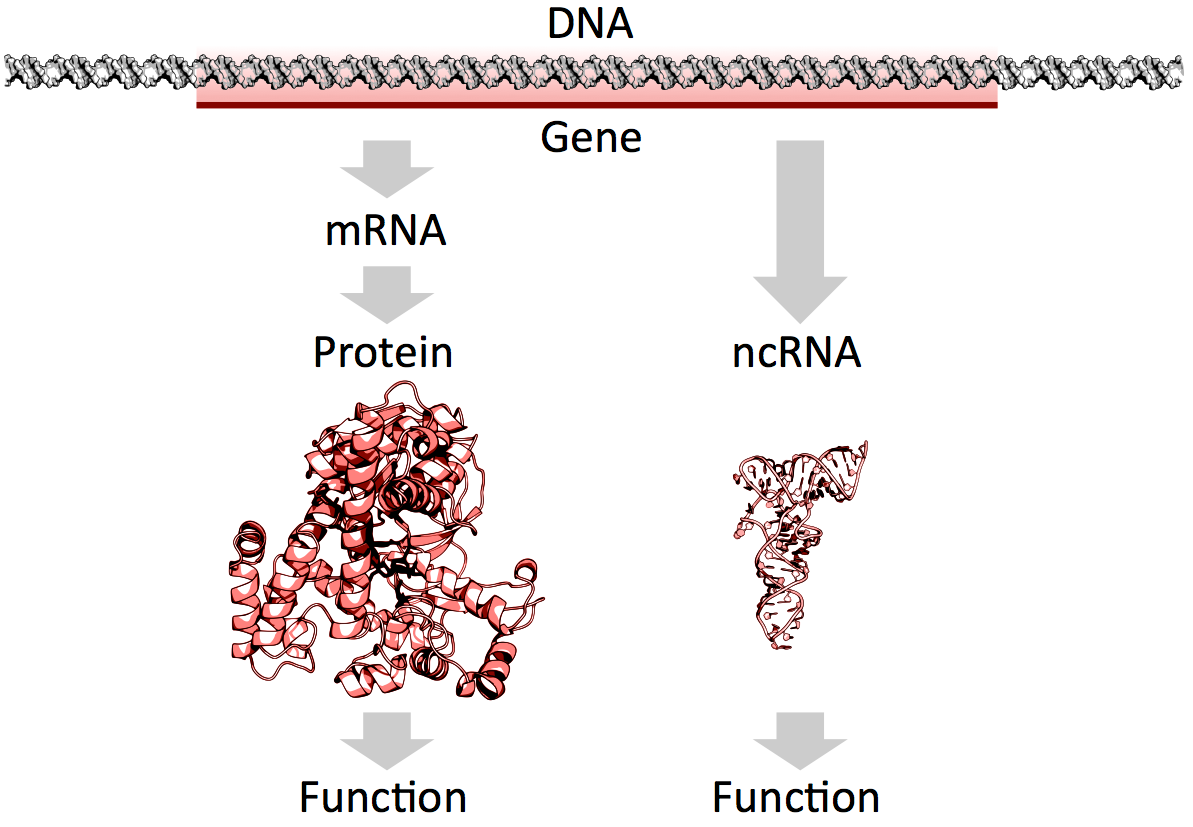

mRNAs vs. ncRNAs (credit: Thomas Shafee/CC)

Of the 3 billion letters in the human genome, only two per cent make up the protein-coding genes. The genes are copied, or transcribed, into messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, which provide templates for building proteins that do most of the work in the cell. Much of the remaining 98 per cent of the genome was initially considered by some as lacking in functional importance. However, large swaths of the non-coding genome — between half and three quarters of it — are also copied into RNA.

So then what might the resulting ncRNAs do? That depends on whom you ask. Some researchers believe that most ncRNAs have no function, that they are just a by-product of the genome’s powerful transcription machinery that makes mRNA. However, it is emerging that many ncRNAs do have important roles in gene regulation — some ncRNAs act as carriages for shuttling the mRNAs around the cell, or provide a scaffold for other proteins and RNAs to attach to and do their jobs.

But the majority of available data has trickled in piecemeal or through serendipitous discovery. And with emerging evidence that ncRNAs could drive disease progression, such as cancer metastasis, there was a great need for a technology that would allow a systematic functional analysis of ncRNAs.

“Up until now, with existing methods, you had to know what you are looking for because they all require you to have some information about the RNA of interest. The power of our method is that you don’t need to preselect your candidates; you can see what’s occurring globally in cells, and use that information to look at interesting things we have not seen before and how they are affecting biology,” says Eesha Sharma, a PhD candidate in Blencowe’s group who, along with postdoctoral fellow Tim Sterne-Weiler, co-developed the method.

A new ncRNA identification tool

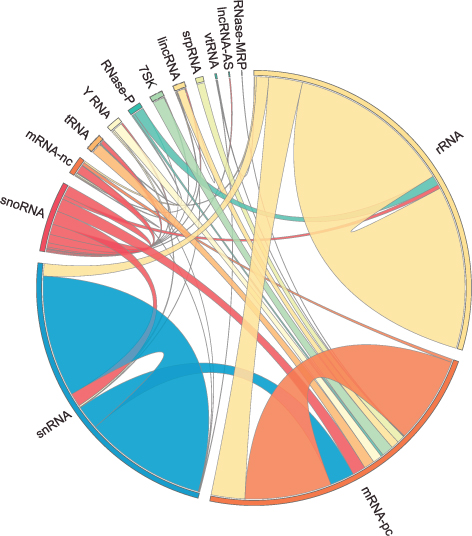

The human RNA-RNA interactome, showing interactions detected by LIGR-seq (credit: University of Toronto)

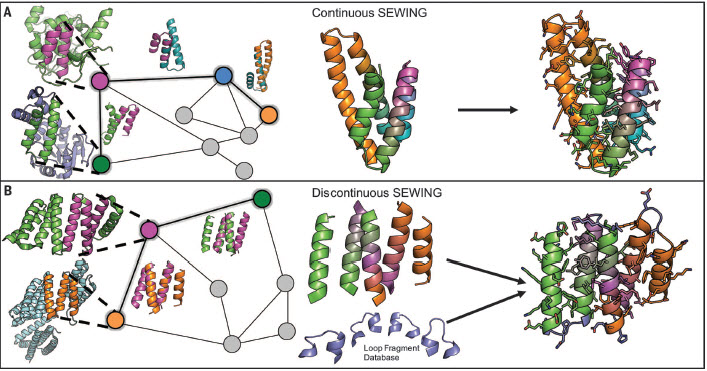

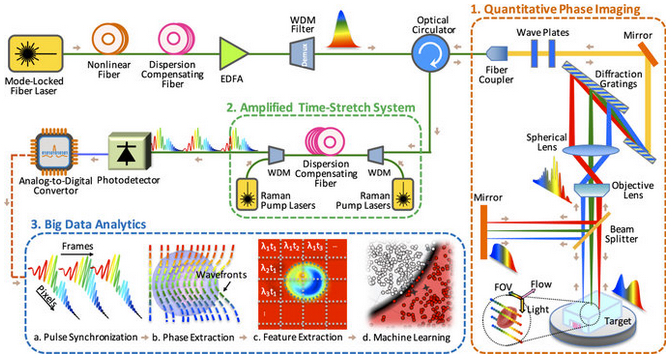

The new ‘‘LIGation of interacting RNA and high-throughput sequencing’’ (LIGR-seq) tool captures interactions between different RNA molecules. When two RNA molecules have matching sequences — strings of letters copied from the DNA blueprint — they will stick together like Velcro. With LIGR-seq, the paired RNA structures are removed from cells and analyzed by state-of-the-art sequencing methods to precisely identify the RNAs that are stuck together.

“Most researchers in the life sciences agree that there’s an urgent need to understand what ncRNAs do. This technology will open the door to developing a new understanding of ncRNA function,” says Blencowe, who is also a professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics.

Not having to rely on pre-existing knowledge will boost the discovery of RNA pairs that have never been seen before. Scientists can also, for the first time, look at RNA interactions as they occur in living cells, in all their complexity, unlike in the juices of mashed up cells that they had to rely on before. This is a bit like moving on to explore marine biology from collecting shells on the beach to scuba-diving among the coral reefs, where the scope for discovery is so much bigger.

Actually, ncRNAs come in multiple flavors: there’s rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, piRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA, to name a few, where prefixes reflect the RNA’s place in the cell or some aspect of its function. But the truth is that no one really knows the extent to which these ncRNAs control what goes on in the cell, or how they do this.

Discoveries

Nonetheless, the new technology developed by Blencowe’s group has been able to pick up new interactions involving all classes of RNAs and has already revealed some unexpected findings.

The team discovered new roles for small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), which normally guide chemical modifications of other ncRNAs. It turns out that some snoRNAs can also regulate stability of a set of protein-coding mRNAs. In this way, snoRNAs can also directly influence which proteins are made, as well as their abundance, adding a new level of control in cell biology.

And this is only the tip of the iceberg; the researchers plan to further develop and apply their technology to investigate the ncRNAs in different settings.

“We would like to understand how ncRNAs function during development. We are particularly interested in their role in the formation of neurons. But we will also use our method to discover and map changes in RNA-RNA interactions in the context of human diseases,” says Blencowe.

Abstract of Global Mapping of Human RNA-RNA Interactions

The majority of the human genome is transcribed into non-coding (nc)RNAs that lack known biological functions or else are only partially characterized. Numerous characterized ncRNAs function via base pairing with target RNA sequences to direct their biological activities, which include critical roles in RNA processing, modification, turnover, and translation. To define roles for ncRNAs, we have developed a method enabling the global-scale mapping of RNA-RNA duplexes crosslinked in vivo, “LIGation of interacting RNA followed by high-throughput sequencing” (LIGR-seq). Applying this method in human cells reveals a remarkable landscape of RNA-RNA interactions involving all major classes of ncRNA and mRNA. LIGR-seq data reveal unexpected interactions between small nucleolar (sno)RNAs and mRNAs, including those involving the orphan C/D box snoRNA, SNORD83B, that control steady-state levels of its target mRNAs. LIGR-seq thus represents a powerful approach for illuminating the functions of the myriad of uncharacterized RNAs that act via base-pairing interactions.