A silicon-based metalens just 30 micrometers thick is mounted on a transparent, stretchy polymer film. The colored iridescence is produced by the large number of nanostructures within the metalens. (credit:Harvard SEAS)

Researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have developed a breakthrough electronically controlled artificial eye. The thin, flat, adaptive silicon nanostructure (“metalens”) can simultaneously control focus, astigmatism, and image shift (three of the major contributors to blurry images) in real time, which the human eye (and eyeglasses) cannot do.

The 30-micrometers-thick metalens makes changes laterally to achieve optical zoom, autofocus, and image stabilization — making it possible to replace bulky lens systems in future optical systems used in eyeglasses, cameras, cell phones, and augmented and virtual reality devices.

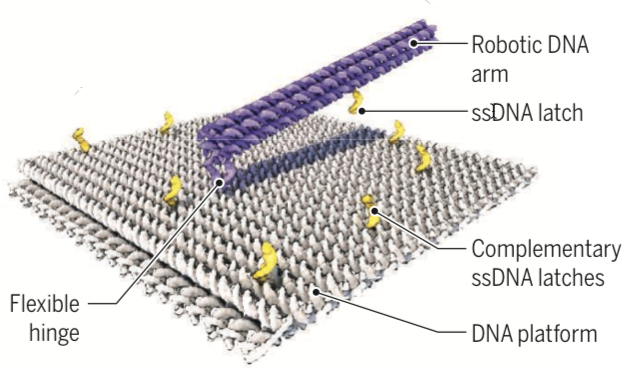

The research is described in an open-access paper in Science Advances. In another paper recently published in Optics Express, the researchers demonstrated the design and fabrication of metalenses up to centimeters or more in diameter.* That makes it possible to unify two industries: semiconductor manufacturing and lens-making. So the same technology used to make computer chips will be used to make metasurface-based optical components, such as lenses.

The adaptive metalens (right) focuses light rays onto an image sensor (left), such as one in a camera. An electrical signal controls the shape of the metalens to produce the desired optical wavefront patterns (shown in red), resulting in improved images. In the future, adaptive metalenses will be built into imaging systems, such as cell phone cameras and microscopes, enabling flat, compact autofocus as well as the capability for simultaneously correcting optical aberrations and performing optical image stabilization, all in a single plane of control. (credit: Second Bay Studios/Harvard SEAS)

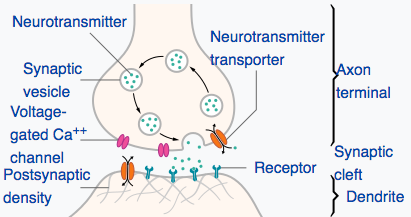

Simulating the human eye’s lens and ciliary muscles

In the human eye, the lens is surrounded by ciliary muscle, which stretches or compresses the lens, changing its shape to adjust its focal length. To achieve that function, the researchers adhered a metalens to a thin, transparent dielectric elastomer actuator (“artificial muscle”). The researchers chose a dielectic elastomer with low loss — meaning light travels through the material with little scattering — to attach to the lens.

(Top) Schematic of metasurface and dielectric elastomer actuators (“artificial muscles”), showing how the new artificial muscles change focus, similar to how the ciliary muscle in the eye work. An applied voltage supplies transparent, stretchable electrode layers (gray), made up of single-wall carbon-nanotube nanopillars, with electrical charges (acting as a capacitor). The resulting electrostatic attraction compresses (red arrows) the dielectric elastomer actuators (artificial muscles) in the thickness direction and expands (black arrows) the elastomers in the lateral direction. The silicon metasurface (in the center), applied by photolithography, can simultaneously focus, control aberrations caused by astigmatisms, and perform image shift. (Bottom) Photo of actual device. (credit: Alan She et al./Sci. Adv.)

Next, the researchers aim to further improve the functionality of the lens and decrease the voltage required to control it.

The research was performed at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, supported in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and by the National Science Foundation. This work was performed in part at the Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), which is supported by the National Science Foundation. The Harvard Office of Technology Development is exploring commercialization opportunities.

* To build the artificial eye with a larger (more functional) metalens, the researchers had to develop a new algorithm to shrink the file size to make it compatible with the technology currently used to fabricate integrated circuits.

** “All optical systems with multiple components — from cameras to microscopes and telescopes — have slight misalignments or mechanical stresses on their components, depending on the way they were built and their current environment, that will always cause small amounts of astigmatism and other aberrations, which could be corrected by an adaptive optical element,” said Alan She, a graduate student at SEAS and first author of the paper. “Because the adaptive metalens is flat, you can correct those aberrations and integrate different optical capabilities onto a single plane of control. Our results demonstrate the feasibility of embedded autofocus, optical zoom, image stabilization, and adaptive optics, which are expected to become essential for future chip-scale image sensors and Furthermore, the device’s flat construction and inherently lateral actuation without the need for motorized parts allow for highly stackable systems such as those found in stretchable electronic eye camera sensors, providing possibilities for new kinds of imaging systems.”

Abstract of Adaptive metalenses with simultaneous electrical control of focal length, astigmatism, and shift

Focal adjustment and zooming are universal features of cameras and advanced optical systems. Such tuning is usually performed longitudinally along the optical axis by mechanical or electrical control of focal length. However, the recent advent of ultrathin planar lenses based on metasurfaces (metalenses), which opens the door to future drastic miniaturization of mobile devices such as cell phones and wearable displays, mandates fundamentally different forms of tuning based on lateral motion rather than longitudinal motion. Theory shows that the strain field of a metalens substrate can be directly mapped into the outgoing optical wavefront to achieve large diffraction-limited focal length tuning and control of aberrations. We demonstrate electrically tunable large-area metalenses controlled by artificial muscles capable of simultaneously performing focal length tuning (>100%) as well as on-the-fly astigmatism and image shift corrections, which until now were only possible in electron optics. The device thickness is only 30 μm. Our results demonstrate the possibility of future optical microscopes that fully operate electronically, as well as compact optical systems that use the principles of adaptive optics to correct many orders of aberrations simultaneously.

Abstract of Large area metalenses: design, characterization, and mass manufacturing

Optical components, such as lenses, have traditionally been made in the bulk form by shaping glass or other transparent materials. Recent advances in metasurfaces provide a new basis for recasting optical components into thin, planar elements, having similar or better performance using arrays of subwavelength-spaced optical phase-shifters. The technology required to mass produce them dates back to the mid-1990s, when the feature sizes of semiconductor manufacturing became considerably denser than the wavelength of light, advancing in stride with Moore’s law. This provides the possibility of unifying two industries: semiconductor manufacturing and lens-making, whereby the same technology used to make computer chips is used to make optical components, such as lenses, based on metasurfaces. Using a scalable metasurface layout compression algorithm that exponentially reduces design file sizes (by 3 orders of magnitude for a centimeter diameter lens) and stepper photolithography, we show the design and fabrication of metasurface lenses (metalenses) with extremely large areas, up to centimeters in diameter and beyond. Using a single two-centimeter diameter near-infrared metalens less than a micron thick fabricated in this way, we experimentally implement the ideal thin lens equation, while demonstrating high-quality imaging and diffraction-limited focusing.