(credit: Neuralink Corp.)

It’s the year 2021. A quadriplegic patient has just had one million “neural lace” microparticles injected into her brain, the world’s first human with an internet communication system using a wireless implanted brain-mind interface — and empowering her as the first superhuman cyborg. …

No, this is not a science-fiction movie plot. It’s the actual first public step — just four years from now — in Tesla CEO Elon Musk’s business plan for his latest new venture, Neuralink. It’s now explained for the first time on Tim Urban’s WaitButWhy blog.

Dealing with the superintelligence existential risk

Such a system would allow for radically improved communication between people, Musk believes. But for Musk, the big concern is AI safety. “AI is obviously going to surpass human intelligence by a lot,” he says. “There’s some risk at that point that something bad happens, something that we can’t control, that humanity can’t control after that point — either a small group of people monopolize AI power, or the AI goes rogue, or something like that.”

“This is what keeps Elon up at night,” says Urban. “He sees it as only a matter of time before superintelligent AI rises up on this planet — and when that happens, he believes that it’s critical that we don’t end up as part of ‘everyone else.’ That’s why, in a future world made up of AI and everyone else, he thinks we have only one good option: To be AI.”

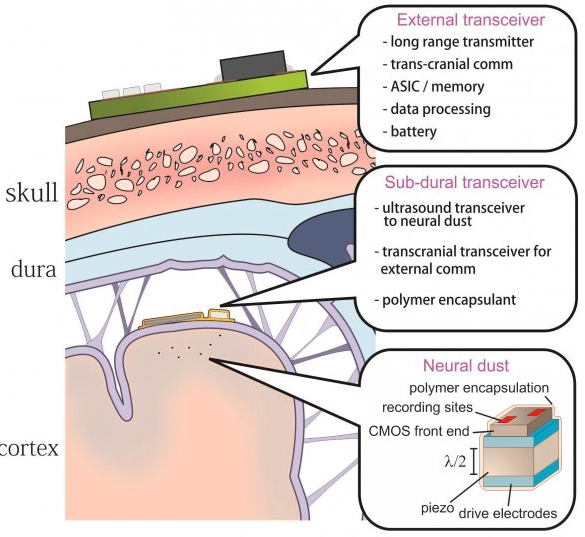

Neural dust: an ultrasonic, low power solution for chronic brain-machine interfaces (credit: Swarm Lab/UC Berkeley)

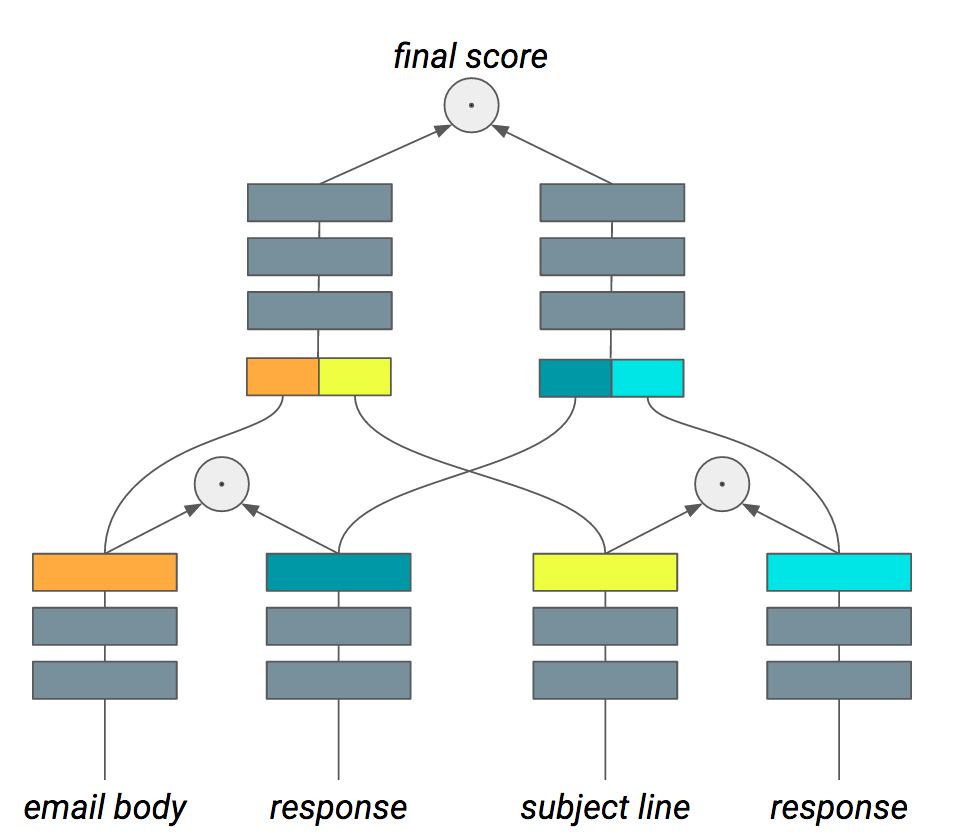

To achieve his, Neuralink CEO Musk has met with more than 1,000 people, narrowing it down initially to eight experts, such as Paul Merolla, who spent the last seven years as the lead chip designer at IBM on their DARPA-funded SyNAPSE program to design neuromorphic (brain-inspired) chips with 5.4 billion transistors (each with 1 million neurons and 256 million synapses), and Dongjin (DJ) Seo, who while at UC Berkeley designed an ultrasonic backscatter system for powering and communicating with implanted bioelectronics called neural dust for recording brain activity.*

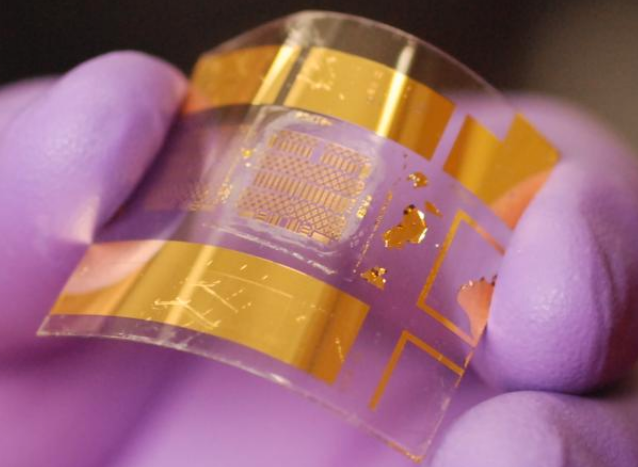

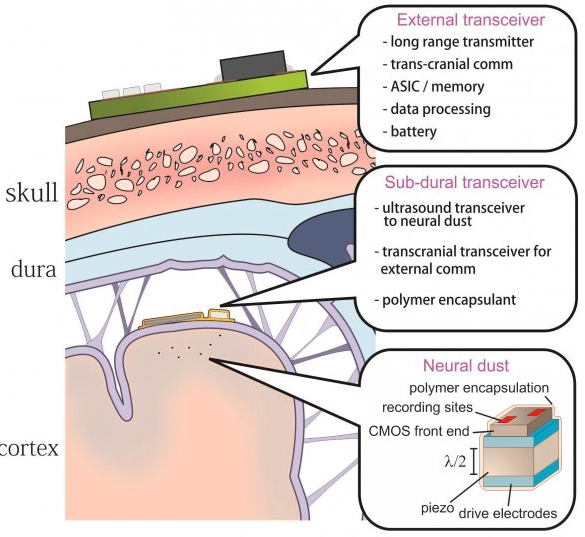

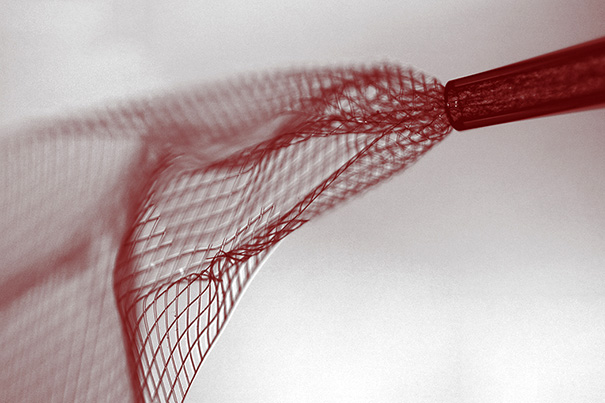

Mesh electronics being injected through sub-100 micrometer inner diameter glass needle into aqueous solution (credit: Lieber Research Group, Harvard University)

Becoming one with AI — a good thing?

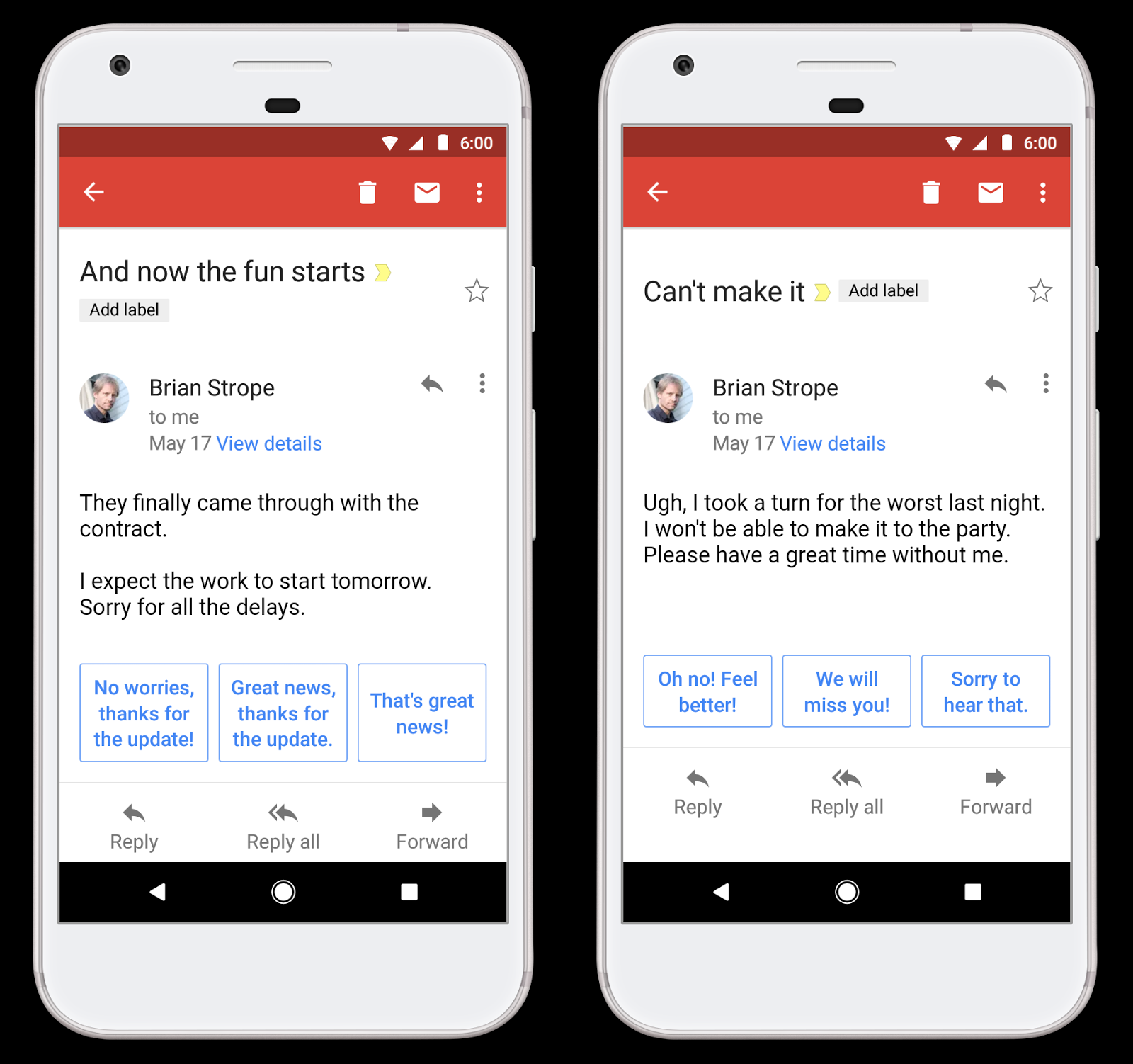

Neuralink’s goal its to create a “digital tertiary layer” to augment the brain’s current cortex and limbic layers — a radical high-bandwidth, long-lasting, biocompatible, bidirectional communicative, non-invasively implanted system made up of micron-size (millionth of a meter) particles communicating wirelessly via the cloud and internet to achieve super-fast communication speed and increased bandwidth (carrying more information).

“We’re going to have the choice of either being left behind and being effectively useless or like a pet — you know, like a house cat or something — or eventually figuring out some way to be symbiotic and merge with AI. … A house cat’s a good outcome, by the way.”

Thin, flexible electrodes mounted on top of a biodegradable silk substrate could provide a better brain-machine interface, as shown in this model. (credit: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

But machine intelligence is already vastly superior to human intelligence in specific areas (such as Google’s Alpha Go) and often inexplicable. So how do we know superintelligence has the best interests of humanity in mind?

“Just an engineering problem”

Musk’s answer: “If we achieve tight symbiosis, the AI wouldn’t be ‘other’ — it would be you and with a relationship to your cortex analogous to the relationship your cortex has with your limbic system.” OK, but then how does an inferior intelligence know when it’s achieved full symbiosis with a superior one — or when AI goes rogue?

Brain-to-brain (B2B) internet communication system: EEG signals representing two words were encoded into binary strings (left) by the sender (emitter) and sent via the internet to a receiver. The signal was then encoded as a series of transcranial magnetic stimulation-generated phosphenes detected by the visual occipital cortex, which the receiver then translated to words (credit: Carles Grau et al./PLoS ONE)

And what about experts in neuroethics, psychology, law? Musk says it’s just “an engineering problem. … If we can just use engineering to get neurons to talk to computers, we’ll have done our job, and machine learning can do much of the rest.”

However, it’s not clear how we could be assured our brains aren’t hacked, spied on, and controlled by a repressive government or by other humans — especially those with a more recently updated software version or covert cyborg hardware improvements.

NIRS/EEG brain-computer interface system using non-invasive near-infrared light for sensing “yes” or “no” thoughts, shown on a model (credit: Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering)

In addition, the devices mentioned in WaitButWhy all require some form of neurosurgery, unlike Facebook’s research project to use non-invasive near-infrared light, as shown in this experiment, for example.** And getting implants for non-medical use approved by the FDA will be a challenge, to grossly understate it.

“I think we are about 8 to 10 years away from this being usable by people with no disability,” says Musk, optimistically. However, Musk does not lay out a technology roadmap for going further, as MIT Technology Review notes.

Nonetheless, Neuralink sounds awesome — it should lead to some exciting neuroscience breakthroughs. And Neuralink now has 16 San Francisco job listings here.

* Other experts: Vanessa Tolosa, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, one of the world’s foremost researchers on biocompatible materials; Max Hodak, who worked on the development of some groundbreaking BMI technology at Miguel Nicolelis’s lab at Duke University, Ben Rapoport, Neuralink’s neurosurgery expert, with a Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from MIT; Tim Hanson, UC Berkeley post-doc and expert in flexible Electrodes for Stable, Minimally-Invasive Neural Recording; Flip Sabes, professor, UCSF School of Medicine expert in cortical physiology, computational and theoretical modeling, and human psychophysics and physiology; and Tim Gardner, Associate Professor of Biology at Boston University, whose lab works on implanting BMIs in birds, to study “how complex songs are assembled from elementary neural units” and learn about “the relationships between patterns of neural activity on different time scales.”

** This binary experiment and the binary Brain-to-brain (B2B) internet communication system mentioned above are the equivalents of the first binary (dot–dash) telegraph message, sent May 24, 1844: ”What hath God wrought?”