A Northeastern University research team has found “extensive” leakage of users’ information — device and user identifiers, locations, and passwords — into network traffic from apps on mobile devices, including iOS, Android, and Windows phones. The researchers have also devised a way to stop the flow.

David Choffnes, an assistant professor in the College of Computer and Information Science, and his colleagues developed a simple, efficient cloud-based system called ReCon. It detects leaks of “personally identifiable information,” alerts users to those breaches, and enables users to control the leaks by specifying what information they want blocked and from whom.

The team’s study followed 31 mobile device users with iOS devices and Android devices who used ReCon for a period of one week to 101 days and then monitored their personal leakages through a ReCon secure webpage.

The results were alarming. “Depressingly, even in our small user study we found 165 cases of credentials being leaked in plaintext,” the researchers wrote.

Of the top 100 apps in each operating system’s app store that participants were using, more than 50 percent leaked device identifiers, more than 14 percent leaked actual names or other user identifiers, 14–26 percent leaked locations, and three leaked passwords in plaintext. In addition to those top apps, the study found similar password leaks from 10 additional apps that participants had installed and used.

The password-leaking apps included MapMyRun, the language app Duolingo, and the Indian digital music app Gaana. All three developers have since fixed the leaks. Several other apps continue to send plaintext passwords into traffic, including a popular dating app.

“What’s really troubling is that we even see significant numbers of apps sending your password, in plaintext readable form, when you log in,” says Choffnes. In a public-WiFi setting, that means anyone running “some pretty simple software” could nab it.

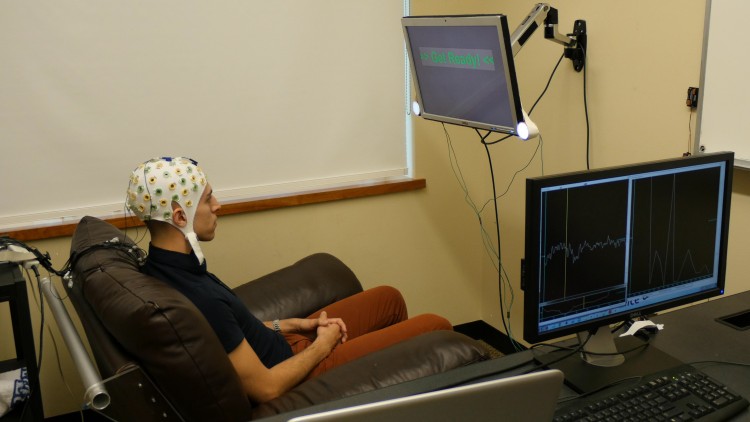

Screen capture of the ReCon user interface. Users can view how their personally identifiable information is leaked, validate the suspected leaks, and create custom filters to block or modify leaks. (credit: Jingjing Ren et al./arXiv)

Apps that track

Access settings for an iPhone app (credit: KurzweilAI)

Apps, like many other digital products, contain software that tracks our comings, goings, and details of who we are. If you look in the privacy setting on your iPhone, you’ll see this statement:

“As applications request access to your data, they will be added in the categories above.”

Those categories include “Location Services,” “Contacts,” “Calendars,” “Reminders,” “Photos,” “Bluetooth Sharing,” and “Camera.”

Although many users don’t realize it, they have control over that access. “When you install an app on a mobile device, it will ask you for certain permissions that you have to approve or deny before you start using the app,” explains Choffnes. “Because I’m a bit of a privacy nut, I’m even selective about which apps I let know my location.” For a navigation app, he says, fine. For others, it’s not so clear.

One reason that apps track you, of course, so is so developers can recover their costs. Many apps are free, tied in with tracking software, supplied by advertising and analytics networks, that generates revenue when users click on the targeted ads that pop up on their phones.

ReCon

Using ReCon is easy, Choffnes says. Participants install a virtual private network, or VPN, on their devices — an easy six- or seven-step process. The VPN then securely transmits users’ data to the system’s server, which runs the ReCon software, identifying when and what information is being leaked.

To learn the status of their information, participants simply log onto the ReCon secure webpage. There they can find things like a Google map pinpointing which of their apps are zapping their location to other destinations and which apps are releasing their passwords into unencrypted network traffic. They can also tell the system what they want to do about it.

“One of the advantages to our approach is you don’t have to tell us your information, for example, your password, email, or gender,” says Choffnes. “Our system is designed to use cues in the network traffic to figure out what kind of information is being leaked. The software then automatically extracts what it suspects is your personal information. We show those findings to users, and they tell us if we are right or wrong. That permits us to continually adapt our system, improving its accuracy.”

The team’s evaluative study showed that ReCon identifies leaks with 98 percent accuracy.

“There are other tools that will show you how you’re being tracked but they won’t necessarily let you do anything,” says Choffnes. “And they are mostly focused on tracking behavior and not the actual personal information that’s being sent out. ReCon covers a wide range of information being sent out over the network about you, and automatically detects when your information is leaked without having to know in advance what that information is. You can [also] set policies to change how your information is being released.”

A demo of ReCon is available here.

Choffnes presented his findings in an open-access paper Monday Nov. 16 at the Data Transparency Lab 2015 Conference, held at the MIT Media Lab.

Abstract of ReCon: Revealing and Controlling Privacy Leaks in Mobile Network Traffic

It is well known that apps running on mobile devices extensively track and leak users’ personally identifiable information (PII); however, these users have little visibility into PII leaked through the network traffic generated by their devices, and have poor control over how, when and where that traffic is sent and handled by third parties. In this paper, we present the design, implementation, and evaluation of ReCon: a cross-platform system that reveals PII leaks and gives users control over them without requiring any special privileges or custom OSes. ReCon leverages machine learning to reveal potential PII leaks by inspecting network traffic, and provides a visualization tool to empower users with the ability to control these leaks via blocking or substitution of PII. We evaluate ReCon’s effectiveness with measurements from controlled experiments using leaks from the 100 most popular iOS, Android, and Windows Phone apps, and via an IRB-approved user study with 31 participants. We show that ReCon is accurate, efficient, and identifies a wider range of PII than previous approaches.