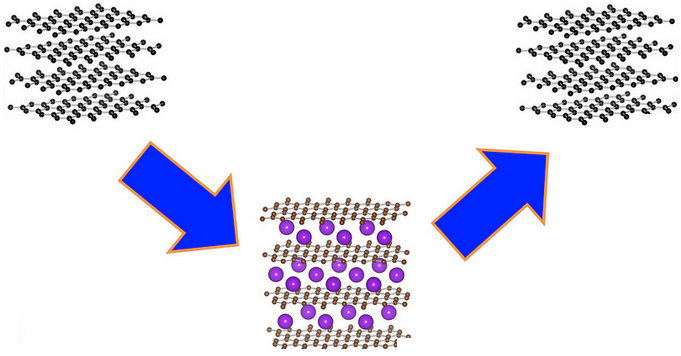

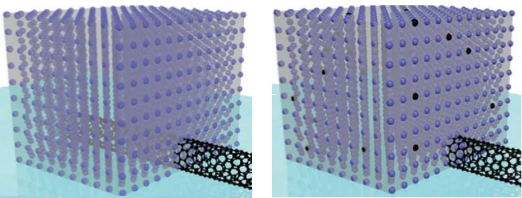

This schematic shows the components of the optical rectenna developed at the Georgia Institute of Technology (credit: Thomas Bougher, Georgia Tech)

Using nanometer-scale components, Georgia Institute of Technology researchers have demonstrated the first optical rectenna, a device that combines the functions of an antenna and a rectifier diode to convert light directly into DC current.

Based on multiwall carbon nanotubes and tiny rectifiers fabricated onto them, the optical rectennas could provide a new technology for energy harvesters, including photodetectors that would operate without the need for cooling, convert waste heat to electricity, and ultimately, efficiently capture solar energy.

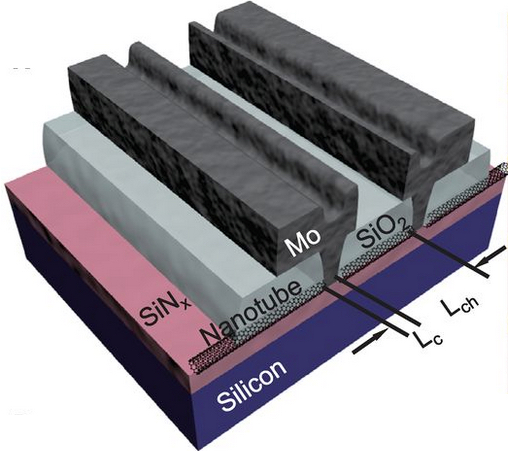

In the new devices, the carbon nanotubes act as antennas to capture light from the Sun or other sources. As the waves of light hit the nanotube antennas, they create an oscillating charge that moves through rectifier devices attached to them. The rectifiers switch on and off at record high petahertz speeds, creating a small direct current.

The efficiency of the devices demonstrated so far remains below one percent, but the researchers hope to boost that output by using billions of rectennas in an array, which could produce significant current. They believe a rectenna with commercial potential may be available within a year.

“We could ultimately make solar cells that are twice as efficient at a cost that is ten times lower, and that is to me an opportunity to change the world in a very big way” said Baratunde Cola, an associate professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at Georgia Tech. “As a robust, high-temperature detector, these rectennas could be a completely disruptive technology if we can get to one percent efficiency. If we can get to higher efficiencies, we could apply it to energy conversion technologies and solar energy capture.”

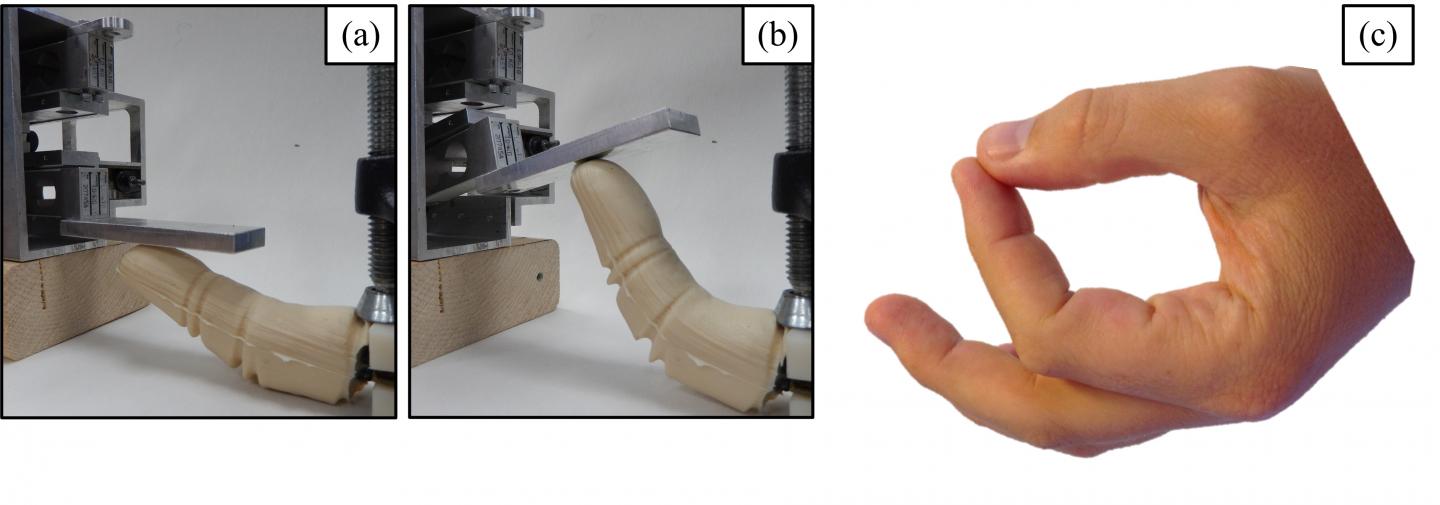

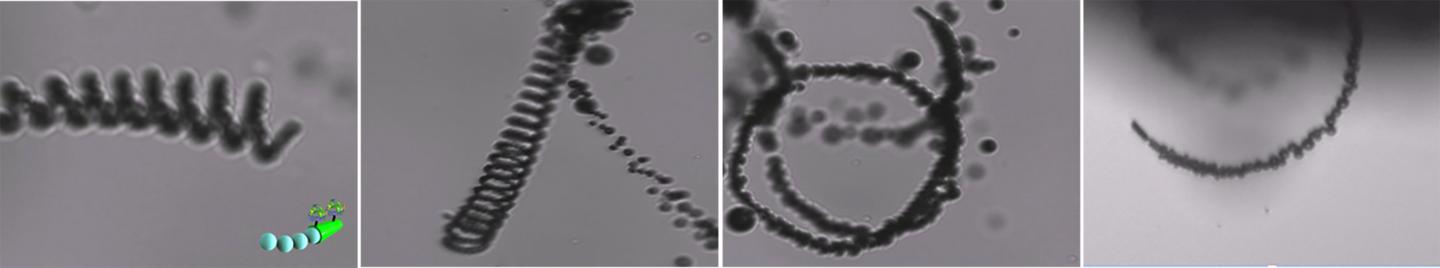

A carbon nanotube optical rectenna converts green laser light to electricity in the laboratory of Baratunde Cola at the Georgia Institute of Technology (credit: Rob Felt, Georgia Tech)

“A rectenna is basically an antenna coupled to a diode, but when you move into the optical spectrum, that usually means a nanoscale antenna coupled to a metal-insulator-metal diode,” Cola explained. “The closer you can get the antenna to the diode, the more efficient it is. So the ideal structure uses the antenna as one of the metals in the diode – which is the structure we made.”

The rectennas fabricated by Cola’s group are grown on rigid substrates, but the goal is to grow them on a foil or other material that would produce flexible solar cells or photodetectors.

Cola sees the rectennas built so far as simple proof of principle. “We think we can reduce the resistance by several orders of magnitude just by improving the fabrication of our device structures,” he said. “Based on what others have done and what the theory is showing us, I believe that these devices could get to greater than 40 percent efficiency.”

The research, supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) Systems Center and the Army Research Office (ARO), is reported September 28 in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

* Developed in the 1960s and 1970s, rectennas have operated at wavelengths as short as ten micrometers, but for more than 40 years researchers have been attempting to make devices at optical wavelengths. There were many challenges: making the antennas small enough to couple optical wavelengths, and fabricating a matching rectifier diode small enough and able to operate fast enough to capture the electromagnetic wave oscillations. But the potential of high efficiency and low cost kept scientists working on the technology.

Fabricating the rectennas begins with growing forests of vertically-aligned carbon nanotubes on a conductive substrate. Using atomic layer chemical vapor deposition, the nanotubes are coated with an aluminum oxide material to insulate them. Finally, physical vapor deposition is used to deposit optically-transparent thin layers of calcium then aluminum metals atop the nanotube forest. The difference of work functions between the nanotubes and the calcium provides a potential of about two electron volts, enough to drive electrons out of the carbon nanotube antennas when they are excited by light.

In operation, oscillating waves of light pass through the transparent calcium-aluminum electrode and interact with the nanotubes. The metal-insulator-metal junctions at the nanotube tips serve as rectifiers switching on and off at femtosecond intervals, allowing electrons generated by the antenna to flow one way into the top electrode. Ultra-low capacitance, on the order of a few attofarads, enables the 10-nanometer diameter diode to operate at these exceptional frequencies.

Georgia Tech | Using nanometer-scale components, researchers have demonstrated the first optical rectenna, a device that combines the functions of an antenna and a rectifier diode to convert light directly into DC current.

Abstract of A carbon nanotube optical rectenna

An optical rectenna—a device that directly converts free-propagating electromagnetic waves at optical frequencies to direct current—was first proposed over 40 years ago, yet this concept has not been demonstrated experimentally due to fabrication challenges at the nanoscale. Realizing an optical rectenna requires that an antenna be coupled to a diode that operates on the order of 1 pHz (switching speed on the order of 1 fs). Diodes operating at these frequencies are feasible if their capacitance is on the order of a few attofarads, but they remain extremely difficult to fabricate and to reliably couple to a nanoscale antenna. Here we demonstrate an optical rectenna by engineering metal–insulator–metal tunnel diodes, with a junction capacitance of ∼2 aF, at the tip of vertically aligned multiwalled carbon nanotubes (∼10 nm in diameter), which act as the antenna. Upon irradiation with visible and infrared light, we measure a d.c. open-circuit voltage and a short-circuit current that appear to be due to a rectification process (we account for a very small but quantifiable contribution from thermal effects). In contrast to recent reports of photodetection based on hot electron decay in a plasmonic nanoscale antenna, a coherent optical antenna field appears to be rectified directly in our devices, consistent with rectenna theory. Finally, power rectification is observed under simulated solar illumination, and there is no detectable change in diode performance after numerous current–voltage scans between 5 and 77 °C, indicating a potential for robust operation.