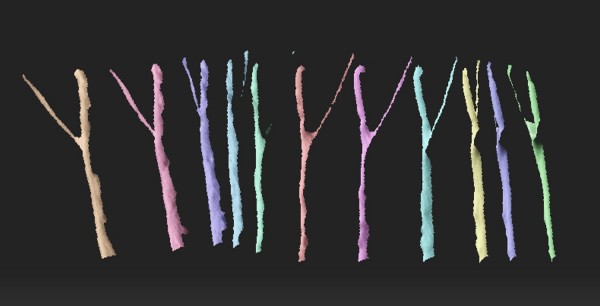

This image shows the self-folding process of smart shape-memory materials with slightly different responses to heat. Using materials that fold at slightly different rates ensures that the components do not interfere with one another during the process. (credit: Qi Laboratory)

Using components made from smart shape-memory materials (which can return to their original shape) with slightly different responses to heat, researchers have demonstrated a “four-dimensional” printing technology that allows for creating complex, self-folding structures.

The technology, developed by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), could be used to create 3-D structures that sequentially fold themselves from components that had been flat or rolled into a tube for shipment. To achieve that, the components could be designed to respond to stimuli such as temperature, moisture or light in a way that is precisely timed to create space structures, deployable medical devices, robots, toys, and a range of other structures.

Shape memory polymers

The researchers used smart shape memory polymers (SMPs) with the ability to remember one shape and change to another programmed shape when uniform heat is applied. Creating objects that change shape in a controlled sequence over time is enabled by printing multiple materials with different dynamic mechanical properties in prescribed patterns throughout the 3-D object.

When these components are then heated, each SMP responds at a different rate to change its shape, depending on its own internal clock. By carefully timing these changes, 3-D objects can be programmed to self-assemble in desired ways.

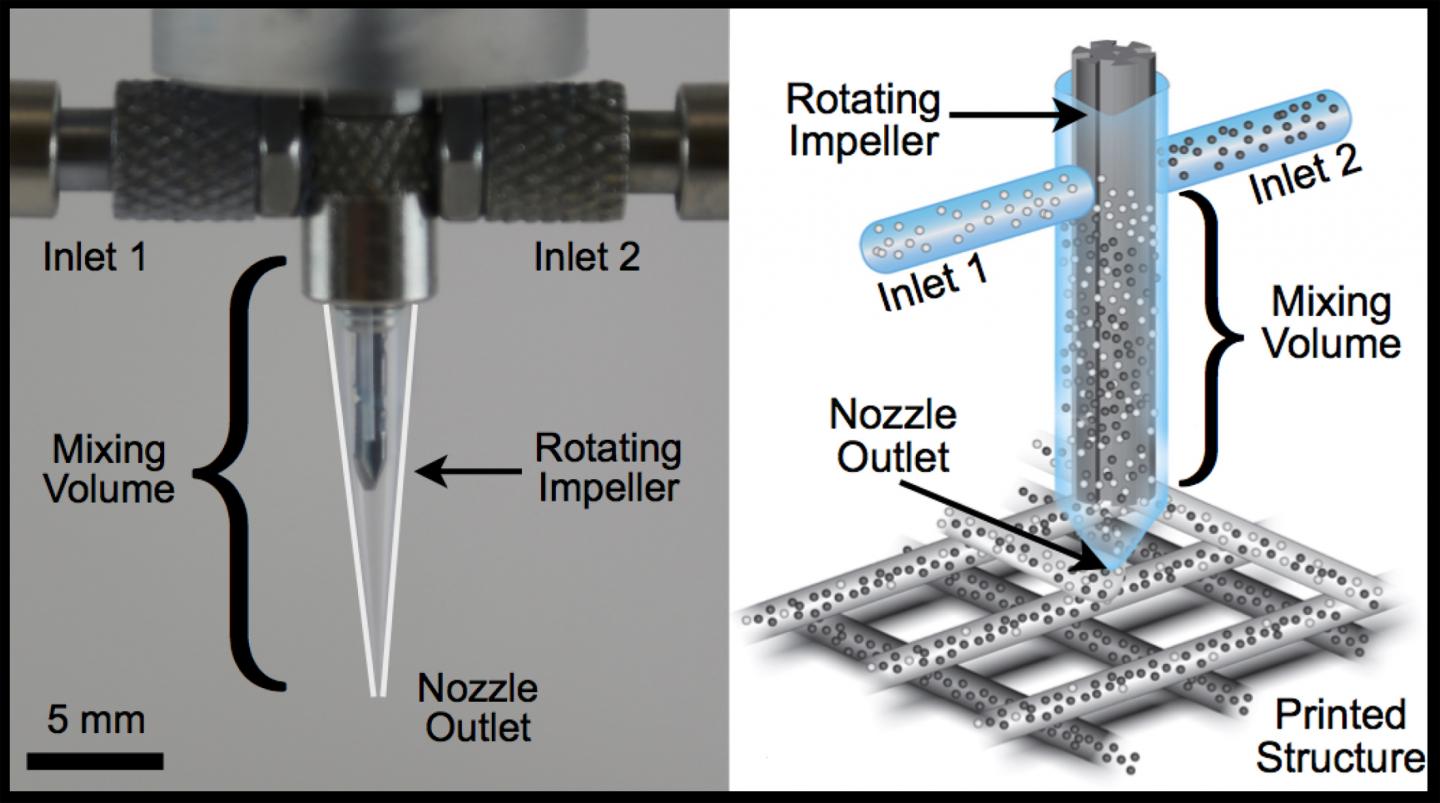

The research creates self-folding structures from 3-D printed patterns containing varying amounts of different smart shape-memory polymers. The patterning, done with a 3-D printer, allows the resulting flat components to have varying temporal response to the same stimuli.*

The team demonstrated the approach with a series of examples, including a mechanism that can be switched from a flat strip into a locked configuration as one end and controllably bends and threads itself through a keyhole. They also demonstrated a flat sheet that can fold itself into a 3-D box with interlocking flaps. These examples all require precise control of the folding sequence of different parts of the structure to avoid collisions of the components during folding.**

Using a 3-D printer, researchers produce smart shape-memory materials with slightly different responses to heat. Heat from water in a tank activates the materials and begins the self-folding process. (Credit: Qi Laboratory, Georgia Tech)

“We have exploited the ability to 3-D print smart polymers and integrate as many as ten different materials precisely into a 3-D structure,” said Martin L. Dunn, a professor at Singapore University of Technology and Design who is also the director of the SUTD Digital Manufacturing and Design Centre. “We are now extending this concept of digital SMPs to enable printing of SMPs with dynamic mechanical properties that vary continuously in 3-D space.”

Morphing aircraft

The research team envisions a broad range of applications for their technology. For example, an unmanned air vehicle might change shape from one designed for a cruise mission to one designed for a dive. Also possible would be 3-D components designed to fold flat or be rolled up into tubes so they could be easily transported, and then later deformed into their intended 3D configuration for use.

The research was reported September 8 in an open-access paper in the journal Scientific Reports. The work is funded by the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the U.S. National Science Foundation, and the Singapore National Research Foundation.

* “Previous efforts to create sequential shape changing components involved placing multiple heaters at specific regions in a component and then controlling the on-and-off time of individual heaters,” explained Jerry Qi, a professor in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering at Georgia Tech. “This earlier approach essentially requires controlling the heat applied throughout the component in both space and time and is complicated. We turned this approach around and used a spatially uniform temperature which is easier to apply and then exploited the ability of different materials to internally control their rate of shape change through their molecular design.”

** The team used companion finite element simulations to predict the responses of the 3-D printed components, which were made from varying ratios of two different commercially available shape-memory polymers. A simplified reduced-order model was also developed to rapidly and accurately describe the physics of the self-folding process. “An important aspect of self-folding is the management of self-collisions, where different portions of the folding structure contact and then block further folding,” the researchers said in their paper. “A metric is developed to predict collisions and is used together with the reduced-order model to design self-folding structures that lock themselves into stable desired configurations.”

Abstract of Sequential Self-Folding Structures by 3D Printed Digital Shape Memory Polymers

Folding is ubiquitous in nature with examples ranging from the formation of cellular components to winged insects. It finds technological applications including packaging of solar cells and space structures, deployable biomedical devices, and self-assembling robots and airbags. Here we demonstrate sequential self-folding structures realized by thermal activation of spatially-variable patterns that are 3D printed with digital shape memory polymers, which are digital materials with different shape memory behaviors. The time-dependent behavior of each polymer allows the temporal sequencing of activation when the structure is subjected to a uniform temperature. This is demonstrated via a series of 3D printed structures that respond rapidly to a thermal stimulus, and self-fold to specified shapes in controlled shape changing sequences. Measurements of the spatial and temporal nature of self-folding structures are in good agreement with the companion finite element simulations. A simplified reduced-order model is also developed to rapidly and accurately describe the self-folding physics. An important aspect of self-folding is the management of self-collisions, where different portions of the folding structure contact and then block further folding. A metric is developed to predict collisions and is used together with the reduced-order model to design self-folding structures that lock themselves into stable desired configurations.