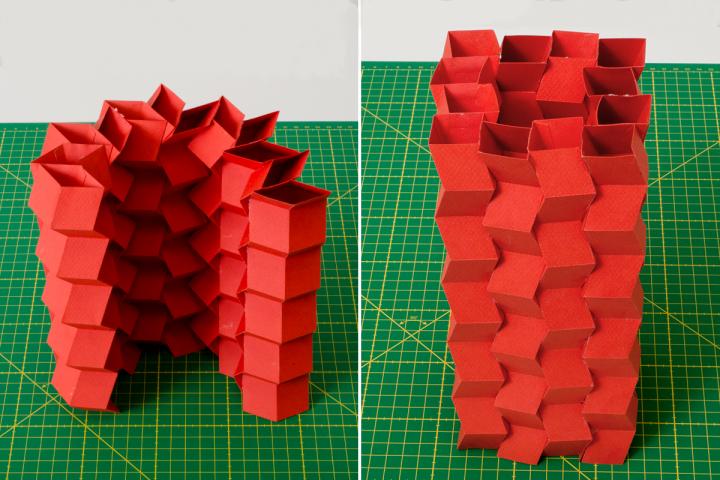

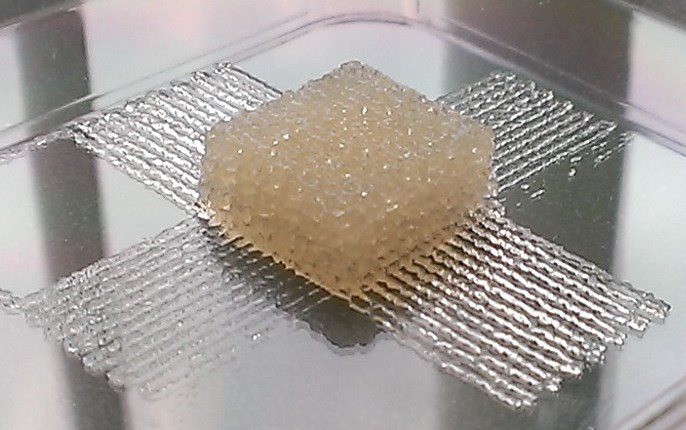

Interlocking origami zigzag paper tubes can be configured to build a variety of structures that have stiffness and function, but can fold compactly for storage or shipping. (credit: Rob Felt)

A new origami “zippered tube” design that makes paper-based (or other thin materials) structures stiff enough to hold weight, yet can fold flat for easy shipping and storage could transform structures ranging from microscopic robots to furniture and even buildings.

That’s what researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the University of Tokyo suggest in a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper.

Such origami structures could include a robotic arm that reaches out and scrunches up, a construction crane that folds to pick up or deliver a load, furniture, and quick-assembling emergency shelters, bridges — and other infrastructure used in the wake of a natural disaster.

Pop-up buildings?

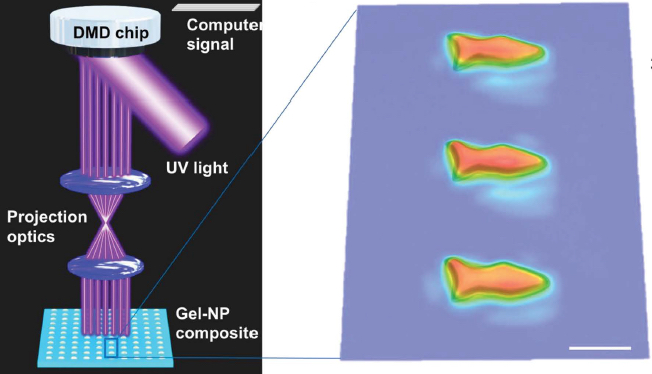

The researchers use a particular origami technique called Miura-ori folding: They make precise, zigzag-folded strips of paper, then glue two strips together to make a tube. While the single strip of paper is highly flexible, the tube is stiffer and does not fold in as many directions.

Interlocking two tubes in zipper-like fashion made them much stiffer and harder to twist or bend, they found. The structure folds up flat, yet rapidly and easily expands to the rigid tube configuration.

The zipper configuration works even with tubes that have different angles of folding. By combining tubes with different geometries, the researchers can make many different three-dimensional structures, such as a bridge, a canopy, or a tower.

Origami “zipper tubes” — interlocking zigzag paper tubes — can be configured to build a variety of structures that have stiffness and function, but can fold compactly for storage or shipping (credit: L. Brian Stauffer)

Transformable structures

“The ability to change functionality in real time is a real advantage in origami,” said Georgia Tech professor Glaucio Paulino. “By having these transformable structures, you can change their functionality and make them adaptable. They are reconfigurable. You can change the material characteristics: You can make them stiffer or softer depending on the intended use.”

The team uses paper prototypes to demonstrate how a thin, flexible sheet can be folded into functional structures, but their techniques could be applied to other thin materials, according to the researchers. Larger-scale applications could combine metal or plastic panels with hinges.

Next, the researchers plan to explore new combinations of tubes with different folding angles to build new structures. They also hope to apply their techniques to other materials and explore applications from large-scale construction to microscopic structures for biomedical devices or robotics.

“All of these ideas apply from the nanoscale and microscale up to large scales and even structures that NASA would deploy into space,” Paulino said. “Depending on your interest, the applications are endless. We have just scratched the surface. Once you have a powerful concept, which we think the zipper coupling is, you can explore applications in many different areas.”

Abstract of Origami tubes assembled into stiff, yet reconfigurable structures and metamaterials

Thin sheets have long been known to experience an increase in stiffness when they are bent, buckled, or assembled into smaller interlocking structures. We introduce a unique orientation for coupling rigidly foldable origami tubes in a “zipper” fashion that substantially increases the system stiffness and permits only one flexible deformation mode through which the structure can deploy. The flexible deployment of the tubular structures is permitted by localized bending of the origami along prescribed fold lines. All other deformation modes, such as global bending and twisting of the structural system, are substantially stiffer because the tubular assemblages are overconstrained and the thin sheets become engaged in tension and compression. The zipper-coupled tubes yield an unusually large eigenvalue bandgap that represents the unique difference in stiffness between deformation modes. Furthermore, we couple compatible origami tubes into a variety of cellular assemblages that can enhance mechanical characteristics and geometric versatility, leading to a potential design paradigm for structures and metamaterials that can be deployed, stiffened, and tuned. The enhanced mechanical properties, versatility, and adaptivity of these thin sheet systems can provide practical solutions of varying geometric scales in science and engineering.

110

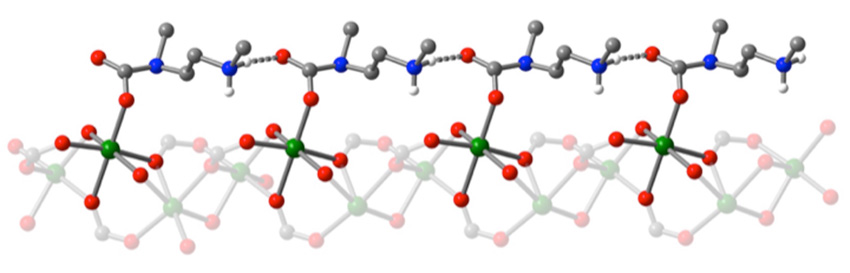

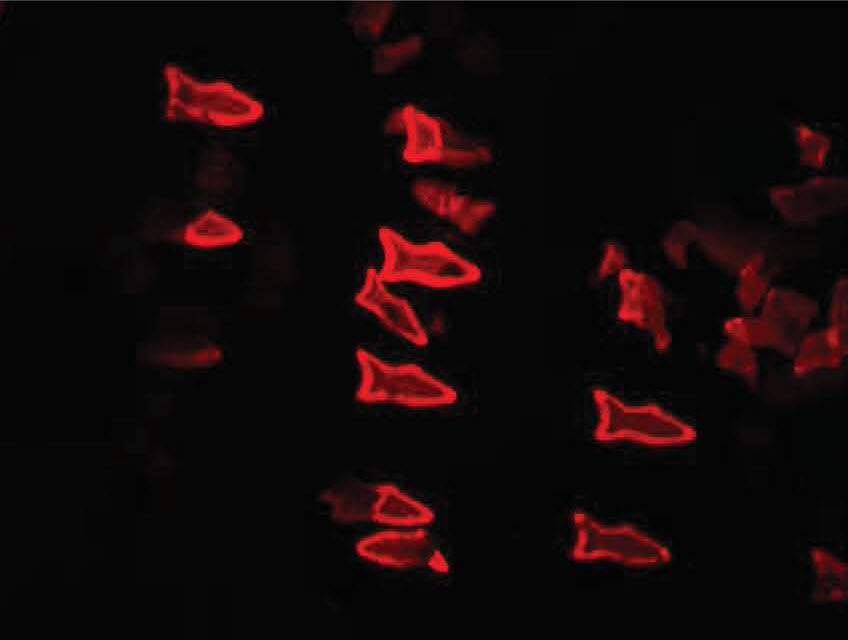

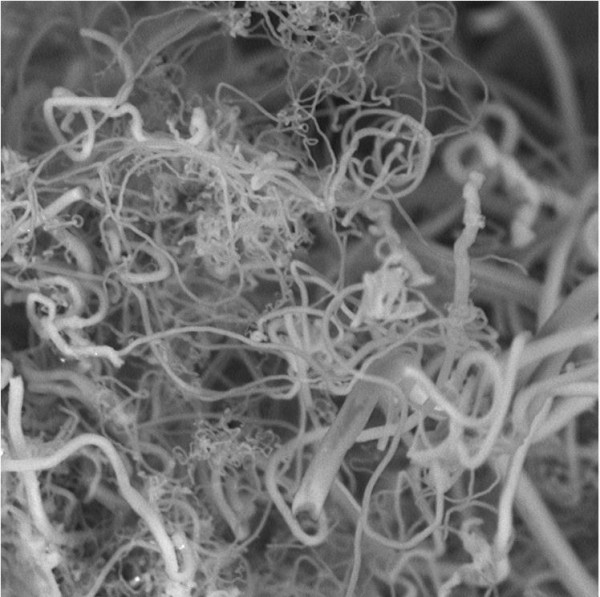

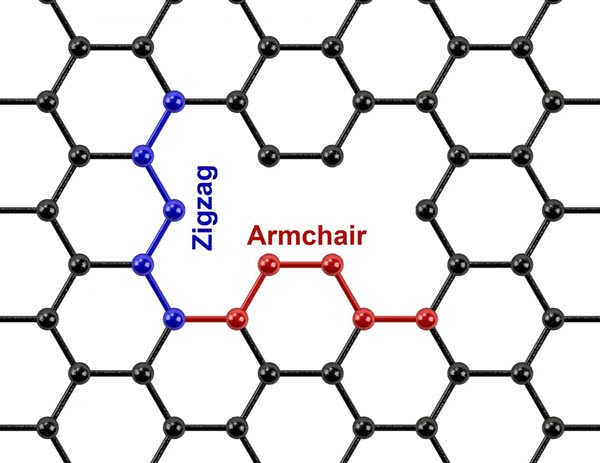

110 directions, are self-defining with predominantly smooth armchair edges, and have tunable width to <10 nm and aspect ratio to >70. In order to realize highly anisotropic ribbons, it is critical to operate in a regime in which the growth rate in the width direction is especially slow, <5 nm h−1. This directional and anisotropic growth enables nanoribbon fabrication directly on conventional semiconductor wafer platforms and, therefore, promises to allow the integration of nanoribbons into future hybrid integrated circuits.

directions, are self-defining with predominantly smooth armchair edges, and have tunable width to <10 nm and aspect ratio to >70. In order to realize highly anisotropic ribbons, it is critical to operate in a regime in which the growth rate in the width direction is especially slow, <5 nm h−1. This directional and anisotropic growth enables nanoribbon fabrication directly on conventional semiconductor wafer platforms and, therefore, promises to allow the integration of nanoribbons into future hybrid integrated circuits.