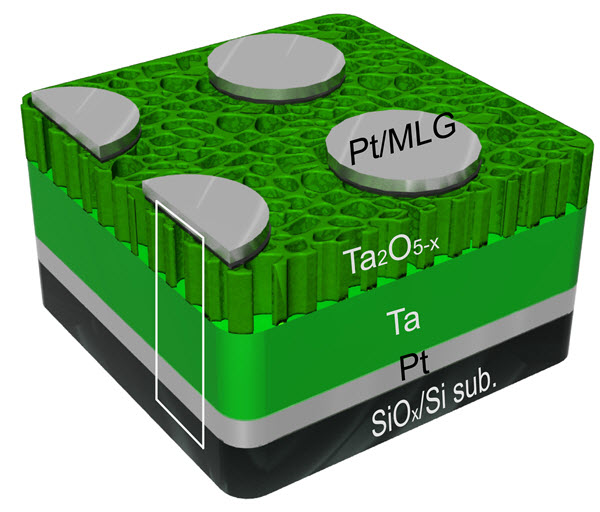

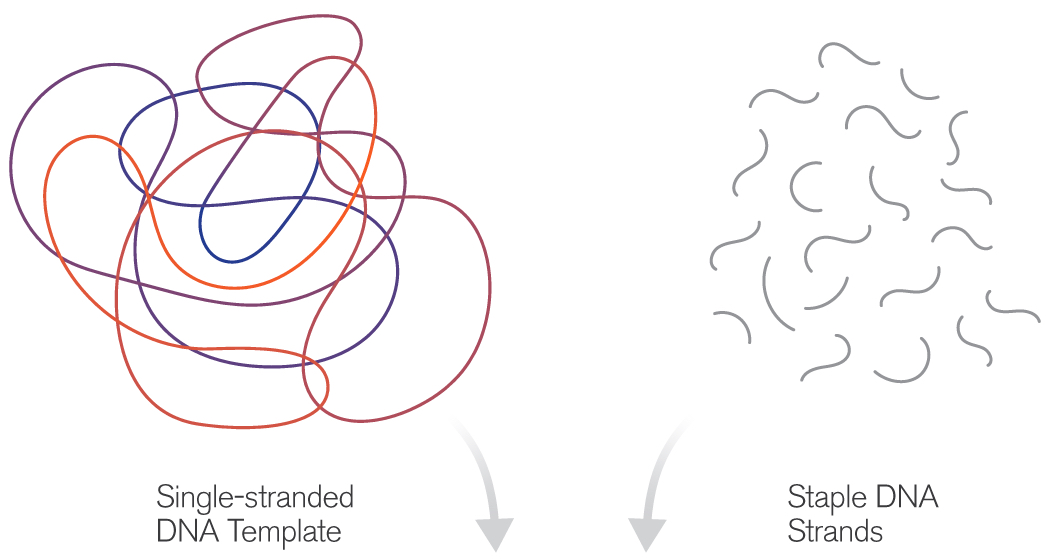

Silica-based paint (credit: American Chemical Society/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab)

Scientists at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab have developed a new, environmentally friendly paint made from glass that bounces sunlight off metal surfaces — keeping them cool and durable.

“Most paints you use on your car or house are based on polymers, which degrade in the ultraviolet light rays of the sun,” says Jason J. Benkoski, Ph.D. “So over time you’ll have chalking and yellowing. Polymers also tend to give off volatile organic compounds, which can harm the environment. That’s why I wanted to move away from traditional polymer coatings to inorganic glass ones.”

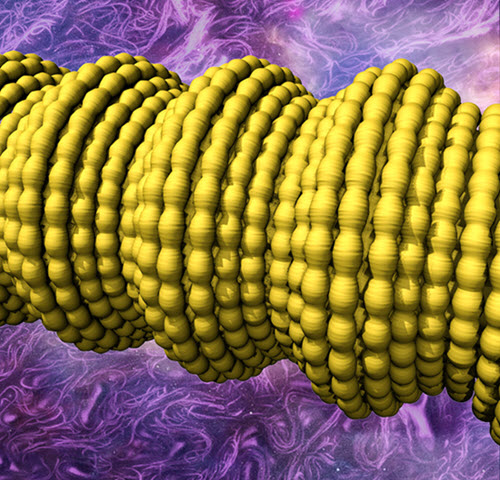

Glass, which is made out of silica, would be an ideal coating. It’s hard, durable and has the right optical properties. But it’s very brittle.

To address that aspect in a new coating, Benkoski, started with silica, one of the most abundant materials in the earth’s crust. He modified one version of it, potassium silicate, that normally dissolves in water. His tweaks transformed the compound so that when it’s sprayed onto a surface and dries, it becomes water-resistant.

Unlike acrylic, polyurethane or epoxy paints, Benkoski’s paint is almost completely inorganic, which should make it last far longer than its counterparts that contain organic compounds. His paint is also designed to expand and contract with metal surfaces to prevent cracking.

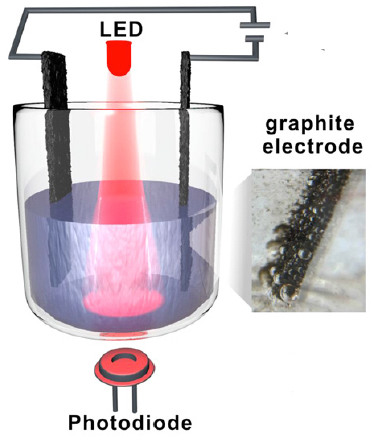

Mixing pigments with the silicate gives the coating an additional property: the ability to reflect all sunlight and passively radiate heat. Since it doesn’t absorb sunlight, any surface coated with the paint will remain at air temperature, or even slightly cooler. That’s key to protecting structures from the sun.

“When you raise the temperature of any material, any device, it almost always by definition ages much more quickly than it normally would,” Benkoski says. “It’s not uncommon for aluminum in direct sunlight to heat 70 degrees Fahrenheit above ambient temperature. If you make a paint that can keep an outdoor surface close to air temperature, then you can slow down corrosion and other types of degradation.”

American Chemical Society | Glass Paint That Can Keep Structures Cool

The paint Benkoski’s lab is developing is intended for use on naval ships (with funding from the U.S. Office of Naval Research), but has many potential commercial applications.

“You might want to paint something like this on your roof to keep heat out and lower your air-conditioning bill in the summer,” he says. It could even go on metal playground slides or bleachers. And it would be affordable. The materials needed to make the coating are abundant and inexpensive.”

Benkoski says he expects his lab will start field-testing the material in about two years.

The researchers presented their work today at the 250th National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), held in Boston through Thursday. It features more than 9,000 presentations on a wide range of science topics.

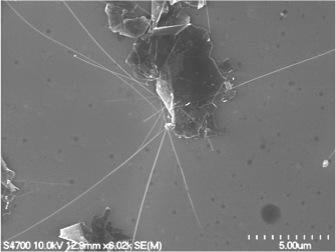

Abstract of Passive cooling with UV-resistant siloxane coatings in direct sunlight

Solar exposure is a leading cause of material degradation in outdoor use. Polymers and other organic materials photo-oxidize due to ultraviolet (UV) exposure. Even in metals, solar heating can cause unwanted property changes through precipitation and Ostwald ripening. In more complex systems, cyclic temperature changes cause fatigue failure wherever thermal expansion mismatch occurs. Most protective coatings designed to prevent these effects inevitably succumb to the same phenomena because of their polymeric matrix. In contrast, siloxane coatings have the potential provide indefinite solar protection because they do not undergo photo-oxidation. This study therefore demonstrates UV-reflective siloxane coatings with low solar absorptance and high thermal emissivity that prevent any increase in temperature above ambient conditions in direct sunlight. Mathematical modeling suggests that even sub-ambient cooling is possible for ZnO-filled potassium silicate. Preventing widespread adoption of potassium silicates until now has been their tendency to crack at large thicknesses, dissolve in water, and delaminate from untreated surfaces. This investigation has successfully addressed these limitations by formulating potassium silicates to behave more like a flexible siloxane polymer than a brittle inorganic glass. The addition of plasticizers (potassium, glycerol), gelling agents (polyethylenimine), and water-insoluble precipitates (zinc silicates, cerium silicates, organosilanes) make it possible to form thick, water resistant coatings that exhibit excellent adhesion even to untreated aluminum surfaces.