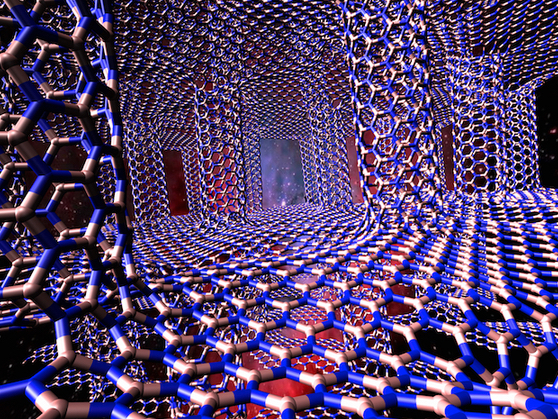

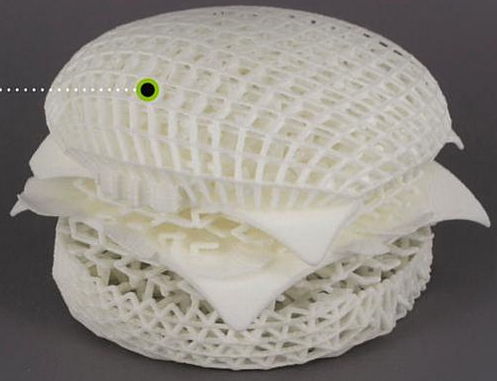

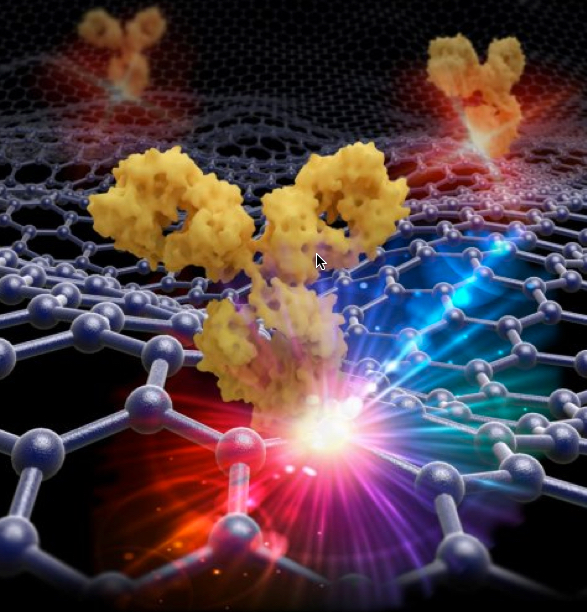

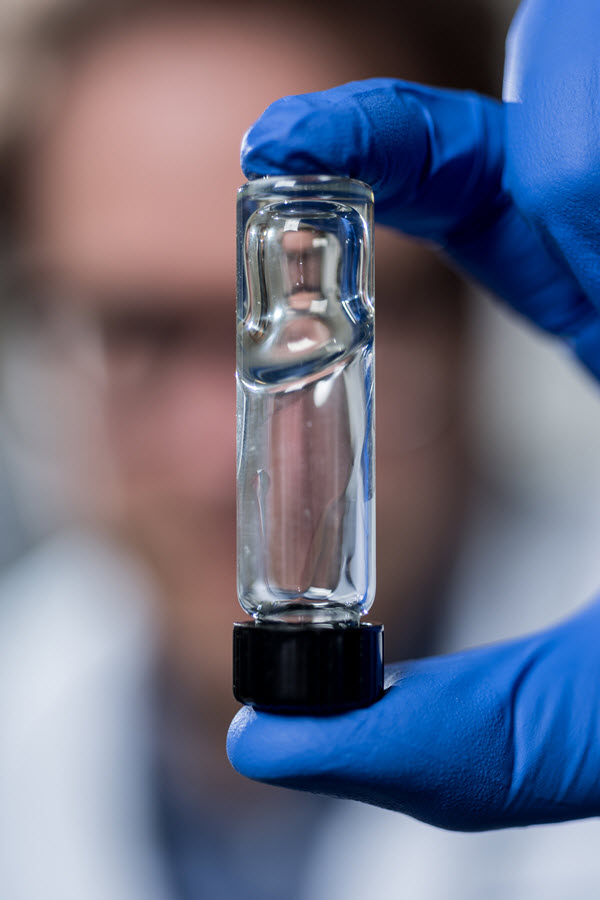

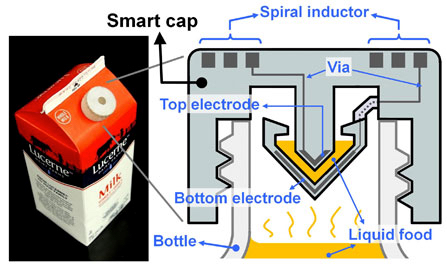

UC Berkeley engineers created a “smart cap” using 3-D-printed plastic with embedded electronics to wirelessly monitor the freshness of milk (credit: Photo and schematic by Sung-Yueh Wu)

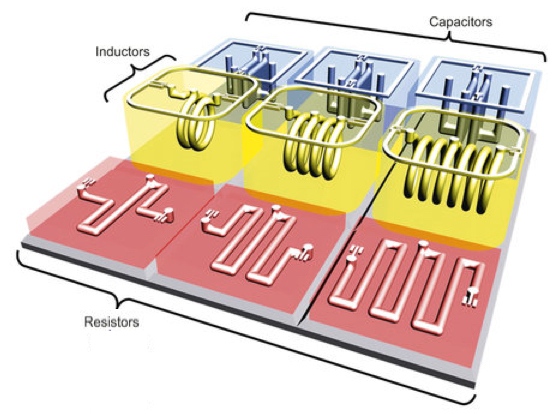

UC Berkeley engineers, in collaboration with colleagues at Taiwan’s National Chiao Tung University, have developed a 3D printing process for creating basic electronic components, such as resistors, inductors, capacitors, and integrated wireless electrical sensing systems.

As a test, they printed a wireless “smart cap” for a milk carton that detected signs of spoilage using embedded sensors.

The findings were published Monday, July 20, in a new open-access journal in the Nature Publishing Group called Microsystems & Nanoengineering.

“Our paper describes the first demonstration of 3-D printing for working basic electrical components, as well as a working wireless sensor,” said senior author Liwei Lin, a professor of mechanical engineering and co-director of the Berkeley Sensor and Actuator Center.“One day, people may simply download 3D-printing files from the Internet with customized shapes and colors and print out useful devices at home.”

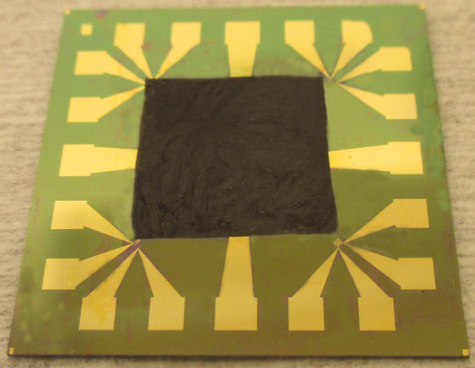

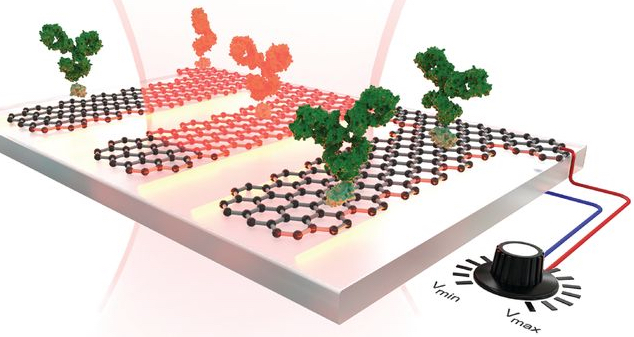

Engineers created a range of 3-D-printed electrical components, including an electrical resistor, inductor, capacitor and an LC tank (integrated inductor-capacitor system) (the penny is used for scale), shown here before removal of wax (credit: Photo by Sung-Yueh Wu)

The researchers started by printing polymers and wax. They then removed the wax, leaving hollow tubes into which liquid metal —- in their experiments they used silver — was injected and then cured.

The shape and design of the metal determined the function of different electrical components. For instance, thin wires acted as resistors, and flat plates were made into capacitors.

To demonstrate their use, the researchers integrated the electronic components into a plastic milk carton cap to monitor signs of spoilage. The “smart cap” was fitted with a capacitor and an inductor to form a resonant circuit. A quick flip of the carton allowed a bit of milk to get trapped in the cap’s capacitor gap, and the entire carton was then left unopened at room temperature (about 71.6 degrees Fahrenheit) for 36 hours.

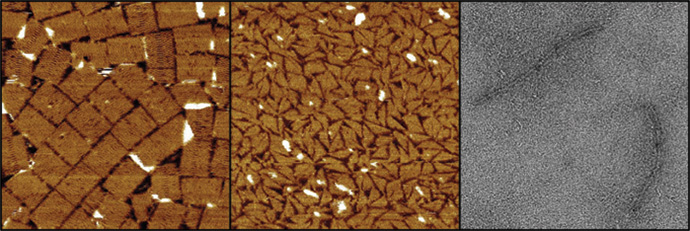

3D-printed components (credit: Sung-Yueh Wu et al./Microsystems & Nanoengineering)

The circuit could detect the changes in electrical signals that accompany increased levels of bacteria. The researchers periodically monitored the changes with a wireless radio-frequency probe at the start of the experiment and every 12 hours thereafter, up to 36 hours. The property of milk changes gradually as it degrades, leading to variations in its electrical characteristics*.

Those changes were detected wirelessly using the smart cap, which found that the peak vibration frequency of the room-temperature milk dropped by 4.3 percent after 36 hours. In comparison, a carton of milk kept in refrigeration at 39.2 degrees Fahrenheit saw a relatively minor 0.12 percent shift in frequency over the same time period.

Cheap DIY electronic circuits

“This 3D-printing technology could eventually make electronic circuits cheap enough to be added to packaging to provide food safety alerts for consumers,” said Lin. “You could imagine a scenario where you can use your cellphone to check the freshness of food while it’s still on the store shelves.”

As 3D printers become cheaper and better, the options for electronics will expand, said Lin, though he does not think people will be printing out their own smartphones or computers anytime soon.

“That would be very difficult because of the extremely small size of modern electronics,” he said. “It might also not be practical in terms of price since current integrated circuits are made by batch fabrication to keep costs low. Instead, I see 3D-printed microelectronic devices as very promising for systems that would benefit from customization.”

Lin said his lab is working on developing this technology for health applications, such as implantable devices with embedded transducers that can monitor blood pressure, muscle strain and drug concentrations.

* As the trapped milk hardened, the dielectric constant increased, increasing the capacitance and thus decreasing the frequency.

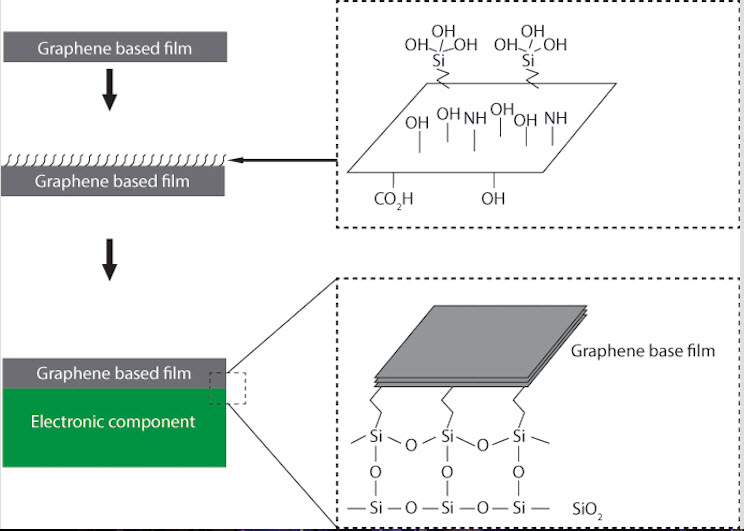

Abstract of 3D-printed microelectronics for integrated circuitry and passive wireless sensors

Three-dimensional (3D) additive manufacturing techniques have been utilized to make 3D electrical components, such as resistors, capacitors, and inductors, as well as circuits and passive wireless sensors. Using the fused deposition modeling technology and a multiple-nozzle system with a printing resolution of 30 μm, 3D structures with both supporting and sacrificial structures are constructed. After removing the sacrificial materials, suspensions with silver particles are injected subsequently solidified to form metallic elements/interconnects. The prototype results show good characteristics of fabricated 3D microelectronics components, including an inductor–capacitor-resonant tank circuitry with a resonance frequency at 0.53 GHz. A 3D “smart cap” with an embedded inductor–capacitor tank as the wireless passive sensor was demonstrated to monitor the quality of liquid food (e.g., milk and juice) wirelessly. The result shows a 4.3% resonance frequency shift from milk stored in the room temperature environment for 36 h. This work establishes an innovative approach to construct arbitrary 3D systems with embedded electrical structures as integrated circuitry for various applications, including the demonstrated passive wireless sensors.