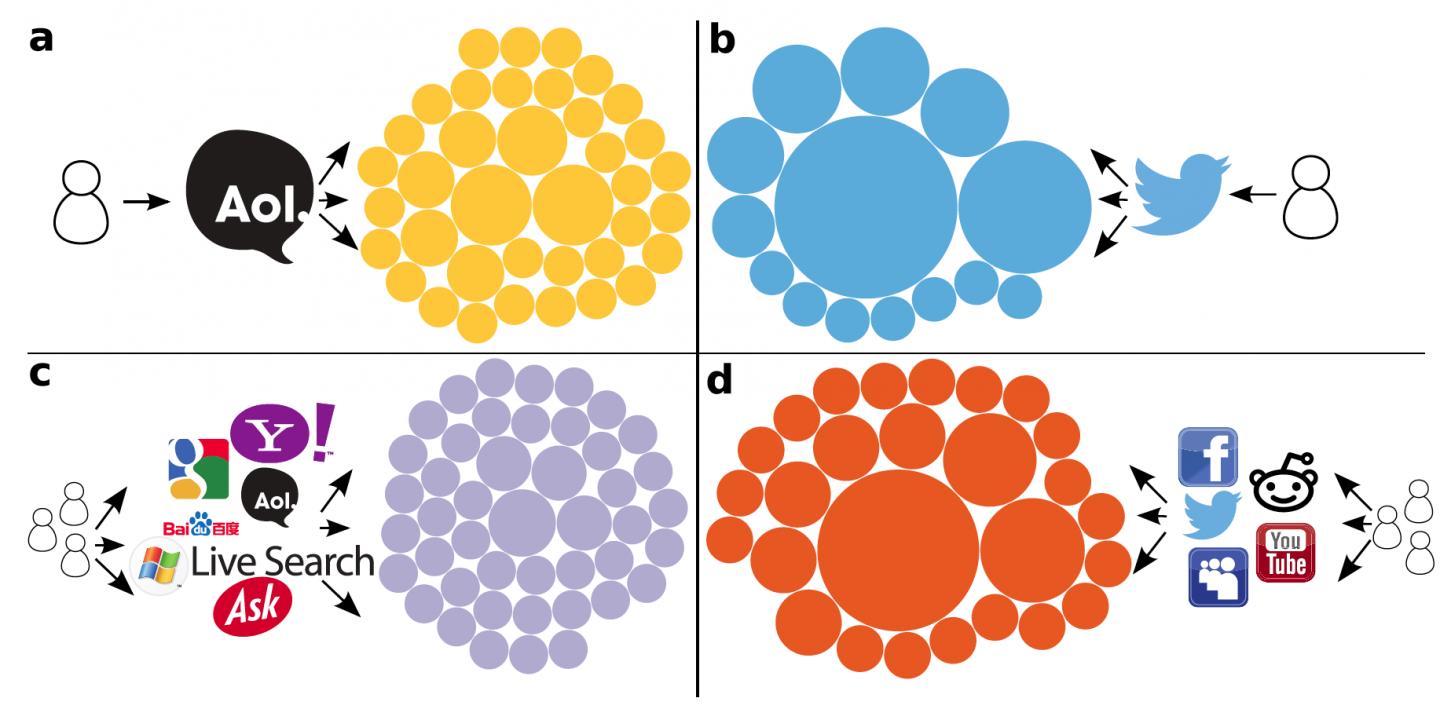

Each circle is proportional to the number of clicks to a website from a single user (a, b) or a group of users (b, d) referred by search engines (a, c) vs. social media (b, d). Social media concentrate clicks to fewer sources, as shown by the larger circles. (credit: Dimitar Nikolov)

Do you find your news and information from social media instead of search engines? If so, you are at risk of becoming trapped in a “collective social bubble.”

That’s according to Indiana University researchers in a study, “Measuring online social bubbles,” recently published in the new open-access online journal PeerJ Computer Science, based on an analysis of more than 100 million Web clicks and 1.3 billion public posts on social media*.

“These findings provide the first large-scale empirical comparison between the diversity of information sources reached through different types of online activity,” said Dimitar Nikolov, a doctoral student in the School of Informatics and Computing at Indiana University (IU), lead author of the study.

Collective social bubble

“Our analysis shows that people collectively access information from a significantly narrower range of sources on social media compared to search engines.”

To measure the diversity of information accessed over each medium, the researchers developed a method that assigned a score for how user clicks from social media versus search engines were distributed across millions of sites.

A lower score indicated users’ Web traffic concentrated on fewer sites; a higher score indicated traffic scattered across more sites. A single click on CNN and nine clicks on MSNBC, for example, would generate a lower score than five clicks on each site.

Overall, the analysis found that people who accessed news on social media scored significantly lower in terms of the diversity of their information sources than users who accessed current information using search engines.

The results show the rise of a “collective social bubble” where news is shared within communities of like-minded individuals, said Nikolov, noting a trend in modern media consumption where “the discovery of information is being transformed from an individual to a social endeavor.”

How “friends” limit your sphere of information

Nikolov noted that people who adopt this behavior as a coping mechanism for “information overload” may not even be aware they’re filtering their access to information by using social media platforms, such as Facebook, where the majority of news stories originate from friends’ postings.

“The rapid adoption of the Web as both a source of knowledge and social space has made it ever more difficult for people to manage the constant stream of news and information arriving on their screens,” added study co-author Filippo Menczer, professor of informatics and computing, director of the Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research. “These results suggest the conflation of these previously distinct activities may be contributing to a growing ‘bubble effect’ in information consumption.”

“Compared to a baseline of information-seeking activities, this evidence shows, empirically, that social media does in fact expose communities and individuals to a significantly narrower range of news sources, despite the many information channels on the medium,” Nikolov said.

It would also be interesting to see how social media as sources compare to news publications, and how social media may make users more vulnerable to propaganda and other forms of information and opinion control.

* IU scientists applied their analysis to three massive sources of information on browsing habits. An anonymous database compiled by the researchers, contained the Web searches of 100,000 users at IU between October 2006 and May 2010 (the primary source). Two other datasets contained identifiers, enabling the scientists to confirm that information access behavior at the community level reflected the behavior of individual users: a dataset containing 18 million clicks by more than half a million users of the AOL search engine in 2006; and 1.3 billion public posts containing links shared by over 89 million people on Twitter between April 2013 and April 2014. To measure the range of news sources accessed by users, the IU scientists used an open directory of news sites, filtering out blogs and wikis, resulting in 3,500 news outlets.

Abstract of Measuring online social bubbles

Social media have become a prevalent channel to access information, spread ideas, and influence opinions. However, it has been suggested that social and algorithmic filtering may cause exposure to less diverse points of view. Here we quantitatively measure this kind of social bias at the collective level by mining a massive datasets of web clicks. Our analysis shows that collectively, people access information from a significantly narrower spectrum of sources through social media and email, compared to a search baseline. The significance of this finding for individual exposure is revealed by investigating the relationship between the diversity of information sources experienced by users at both the collective and individual levels in two datasets where individual users can be analyzed—Twitter posts and search logs. There is a strong correlation between collective and individual diversity, supporting the notion that when we use social media we find ourselves inside “social bubbles.” Our results could lead to a deeper understanding of how technology biases our exposure to new information.