Discovering an element isn't like it was in the good old days. Now scientists spend years trying to smash atoms together in huge particle accelerators.

The post Making New Elements Gets a Lot Harder From Here appeared first on WIRED.

Science and reality

Discovering an element isn't like it was in the good old days. Now scientists spend years trying to smash atoms together in huge particle accelerators.

The post Making New Elements Gets a Lot Harder From Here appeared first on WIRED.

Physicists working at the Large Hadron Collider reported an unusual bump in their signal. But this time, they have no idea where the bump came from.

The post Mysterious LHC Photons Have Physicists Searching for Answers appeared first on WIRED.

(credit: LG)

LG is creating a buzz at CES with its concept demo of the world’s first display that can be rolled up like a newspaper.

LG says they’re aiming for 4K-quality 55-inch screens (the prototype resolution is 1,200 by 810 pixels), BBC reports.

The trick: switching from LED to thinner, more-flexible OLED technology (organic light-emitting diodes), allowing for a 2.57 millimeter-thin display. One limitation: the screen can’t be flattened.

What this design might be useful for in the future is not clear, but experts suggest the technology could soon be used on smartphones and in-car screens that curve around a vehicle’s interior, Daily Mail notes.

LG is also displaying a 55-inch double-sided display that’s as thin as a piece of paper and shows different video images on each side, and two 65-inch “extreme-curve” TVs that bend inwards and outwards.

Human Computation Institute | Dr. Pietro Michelucci

“Human computation” — combining human and computer intelligence in crowd-powered systems — might be what we need to solve the “wicked” problems of the world, such as climate change and geopolitical conflict, say researchers from the Human Computation Institute (HCI) and Cornell University.

In an article published in the journal Science, the authors present a new vision of human computation that takes on hard problems that until recently have remained out of reach.

Humans surpass machines at many things, ranging from visual pattern recognition to creative abstraction. And with the help of computers, these cognitive abilities can be effectively combined into multidimensional collaborative networks that achieve what traditional problem-solving cannot, the authors say.

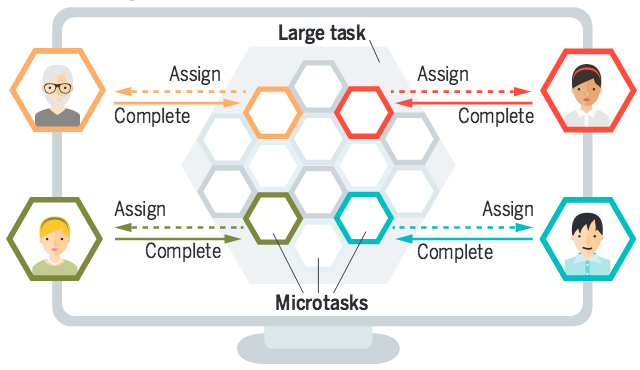

Microtasking

Microtasking: Crowdsourcing breaks large tasks down into microtasks, which can be things at which humans excel, like classifying images. The microtasks are delivered to a large crowd via a user-friendly interface, and the data are aggregated for further processing. (credit: Pietro Michelucci and Janis L. Dickinson/Science)

Most of today’s human-computation systems rely on “microtasking” — sending “micro-tasks” to many individuals and then stitching together the results. For example, 165,000 volunteers in EyeWire have analyzed thousands of images online to help build the world’s most complete map of human retinal neurons.

Another example is reCAPTCHA, a Web widget used by 100 million people a day when they transcribe distorted text into a box to prove they are human.

“Microtasking is well suited to problems that can be addressed by repeatedly applying the same simple process to each part of a larger data set, such as stitching together photographs contributed by residents to decide where to drop water during a forest fire,” the authors note.

But this microtasking approach alone cannot address the tough challenges we face today, say the authors. “A radically new approach is needed to solve ‘wicked problems’ — those that involve many interacting systems that are constantly changing, and whose solutions have unforeseen consequences, such as climate change, disease, and geopolitical conflict, which are dynamic, involve multiple, interacting systems, and have non-obvious secondary effects, such as political exploitation of a pandemic crisis.”

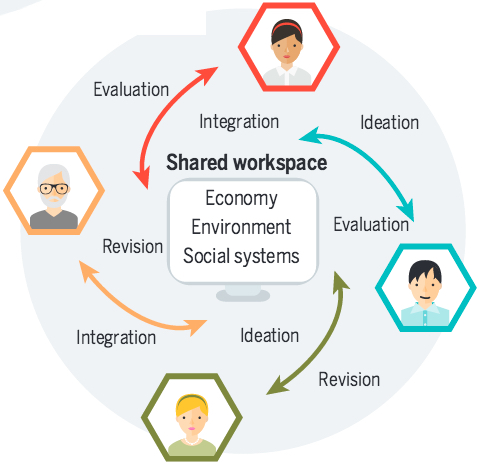

New human-computation technologies

New human-computation technologies: In creating problem-solving ecosystems, researchers are beginning to explore how to combine the cognitive processing of many human contributors with machine-based computing to build faithful models of the complex, interdependent systems that underlie the world’s most challenging problems. (credit: Pietro Michelucci and Janis L. Dickinson/Science)

The authors say new human computation technologies can help build flexible collaborative environments. Recent techniques provide real-time access to crowd-based inputs, where individual contributions can be processed by a computer and sent to the next person for improvement or analysis of a different kind.

This idea is already taking shape in several human-computation projects:

“By enabling members of the general public to play some simple online game, we expect to reduce the time to treatment discovery from decades to just a few years,” says HCI director and lead author, Pietro Michelucci, PhD. “This gives an opportunity for anyone, including the tech-savvy generation of caregivers and early stage AD patients, to take the matter into their own hands.”

Abstract of The power of crowds

Human computation, a term introduced by Luis von Ahn, refers to distributed systems that combine the strengths of humans and computers to accomplish tasks that neither can do alone. The seminal example is reCAPTCHA, a Web widget used by 100 million people a day when they transcribe distorted text into a box to prove they are human. This free cognitive labor provides users with access to Web content and keeps websites safe from spam attacks, while feeding into a massive, crowd-powered transcription engine that has digitized 13 million articles from The New York Times archives. But perhaps the best known example of human computation is Wikipedia. Despite initial concerns about accuracy, it has become the key resource for all kinds of basic information. Information science has begun to build on these early successes, demonstrating the potential to evolve human computation systems that can model and address wicked problems (those that defy traditional problem-solving methods) at the intersection of economic, environmental, and sociopolitical systems.

Princeton University researchers have captured some of the first near-whole-brain recordings of 3-D neural activity of a free-moving animal, and at single-neuron resolution. They studied the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a worm species 1 millimeter long with a nervous system containing just 302 neurons.

The three-dimensional recordings could provide scientists with a better understanding of how neurons coordinate action and perception in animals.

As the researchers report in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, their technique allowed them to record the activity of 77 neurons from the animal’s nervous system, focusing on specific behaviors such as backward or forward motion and turning.

Andrew Leifer/Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics | This video — displayed in quarter-time — shows the four simultaneous video feeds the Princeton researchers used to capture the nematodes’ neural activity. Upper left: the position of the nuclei in all the neurons in an animal’s brain. Upper right: recorded neural activity, indicated by a fluorescent calcium indicator. Lower left: the animal’s posture on the microscope plate, which automatically adjusted to keep the animal within the cameras’ view. Bottom right: a low-magnification fluorescent image of a nematode brain, which contains 302 neurons.

Most previous research on brain activity has focused on small subregions of the brain or is based on observations of organisms that are unconscious or somehow limited in mobility, explained corresponding author Andrew Leifer, an associate research scholar in Princeton’s Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics.

“This system is exciting because it provides the most detailed picture yet of brain-wide neural activity with single-neuron resolution in the brain of an animal that is free to move around,” Leifer said. “Neuroscience is at the beginning of a transition towards larger-scale recordings of neural activity and towards studying animals under more natural conditions,” he said. “This work helps push the field forward on both fronts.”

A current focus in neuroscience is understanding how networks of neurons coordinate to produce behavior. “The technology to record from numerous neurons as an animal goes about its normal activities, however, has been slow to develop,” Leifer said.

Andrew Leifer, Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics | Nematode neural nuclei in 3-D, showing the location of brain-cell nuclei in a nematode’s head.

The simpler nervous system of C. elegans provided the researchers with a more manageable testing ground, but could also reveal information about how neurons work together, which applies to more complex organisms, Leifer said. For instance, the researchers were surprised by the number of neurons involved in the seemingly simple act of turning around.

“One reason we were successful was that we chose to work with a very simple organism,” Leifer said. “It would be immensely more difficult to perform whole-brain recordings in humans. The technology needed to perform similar recordings in humans is many years away. By studying how the brain works in a simple animal like the worm, however, we hope to gain insights into how collections of neurons work that are universal for all brains, even humans.”

The researchers designed an instrument that captures calcium levels in brain cells as they communicate with one another. The level of calcium in each brain cell tells the researchers how active that cell is in its communication with other cells in the nervous system. They induced the nemotodes’ brain cells to generate a protein known as a “calcium indicator” that becomes fluorescent when it comes in contact with calcium.

The researchers used a special type of microscope to record the nematodes’ free movements and also neuron-level calcium activity for more than four minutes and in 3-D. Special software the researchers designed monitored the position of an animal’s head in real time as a motorized platform automatically adjusted to keep the animal within the field of view of a series of cameras.

Andrew Leifer, Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics | A visualization of neural activity in the nematode brain. Upper-left: Each colored sphere represents a neuron, and its location in the drawing shows the position of that neuron in the worm’s head. Upper-right: The size and color of a sphere indicates the level of neural activity (purple spheres: the least amount of activity; large yellow spheres: most significant). By watching neurons that grow and shrink, the viewer can get an impression of the range of neural activity in the worm. Lower left and right panels: The worm’s movement in real time and the worm’s location plotted on a graph.

Leifer said these recordings are very large and the researchers have only begun the process of carefully mining all of the data.

“An exciting next step is to use correlations in our recordings to build mathematical and computer models of how the brain functions,” he said. “We can use these models to generate hypotheses about how neural activity generates behavior. We plan to then test these hypotheses, for example, by stimulating specific neurons in an organism and observing the resulting behavior.”

The ability to acquire large-scale recordings of neuronal activity in awake and unrestrained animals is needed to provide new insights into how populations of neurons generate animal behavior. We present an instrument capable of recording intracellular calcium transients from the majority of neurons in the head of a freely behaving Caenorhabditis elegans with cellular resolution while simultaneously recording the animal’s position, posture, and locomotion. This instrument provides whole-brain imaging with cellular resolution in an unrestrained and behaving animal. We use spinning-disk confocal microscopy to capture 3D volumetric fluorescent images of neurons expressing the calcium indicator GCaMP6s at 6 head-volumes/s. A suite of three cameras monitor neuronal fluorescence and the animal’s position and orientation. Custom software tracks the 3D position of the animal’s head in real time and two feedback loops adjust a motorized stage and objective to keep the animal’s head within the field of view as the animal roams freely. We observe calcium transients from up to 77 neurons for over 4 min and correlate this activity with the animal’s behavior. We characterize noise in the system due to animal motion and show that, across worms, multiple neurons show significant correlations with modes of behavior corresponding to forward, backward, and turning locomotion.

Trying to figure out where the volcanic action in 2016 will be is pretty tricky. I take a stab at some guesses.

The post Keep an Eye Out for These Volcanoes in 2016 appeared first on WIRED.