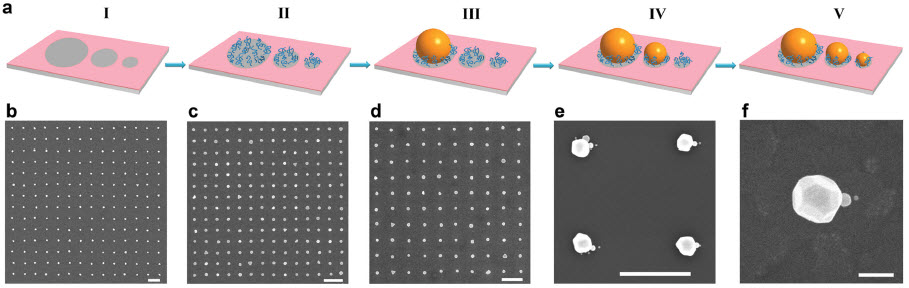

Schematic of the fabrication process and SEM images of the nanostructures used to create a nanolens. (credit: Augustine Urbas et al./Advanced Materials)

Researchers have developed a method of constructing nanolenses that could focus incoming light into a spot much smaller than possible with conventional microscopy, making possible extremely high-resolution imaging or biological sensing.

They precisely aligned three spherical gold nanoparticles of graduated sizes in a string-of-pearls arrangement to produce the focusing effect.

The first step employs the lithographic methods used in making printed circuits to create a chemical mask that leaves a pattern of three spots of decreasing size exposed on a substrate such as silicon or glass that won’t absorb the gold nanoparticles. Lithography allows for extremely precise and delicate patterns, but it can’t produce three-dimensional structures. So the scientists used chemistry to build polymer chains atop the patterned substrate in three dimensions, tethered to the substrate through chemical bonds.

“The chemical contrast between the three spots and the background makes the gold particles go only to the spots,” said Xiaoying Liu, senior research scientist at the University of Chicago’s Institute for Molecular Engineering. To get each of the three sizes of nanospheres to adhere only to its own designated spot, the scientists played with the strength of the chemical interaction between spot and sphere. “We control the size of the different areas in the chemical pattern and we control the interaction potential of the chemistry of those areas with the nanoparticles,” said Nealey.

The spheres are separated by only a few nanometers. It is this tiny separation, coupled with the sequential ordering of the different-sized spheres, that produces the nanolensing effect.

High-resolution sensing using spectroscopy

The scientists are already exploring using this “hot spot” for high-resolution sensing using spectroscopy. “If you put a molecule there, it will interact with the focused light,” said Liu. “The enhanced field at these hot spots will help you to get orders of magnitude stronger signals. And that gives us the opportunity to get ultra-sensitive sensing. Maybe ultimately we can detect single molecules.”

The researchers also foresee applying their manufacturing technique to nanoparticles of other shapes, such as rods and stars.

Scientists at the Air Force Research Laboratory and Florida State University were also involved in the research, which is described in the latest edition of Advanced Materials.

Abstract of Deterministic Construction of Plasmonic Heterostructures in Well-Organized Arrays for Nanophotonic Materials

Plasmonic heterostructures are deterministically constructed in organized arrays through chemical pattern directed assembly, a combination of top-down lithography and bottom-up assembly, and by the sequential immobilization of gold nanoparticles of three different sizes onto chemically patterned surfaces using tailored interaction potentials. These spatially addressable plasmonic chain nanostructures demonstrate localization of linear and nonlinear optical fields as well as nonlinear circular dichroism.