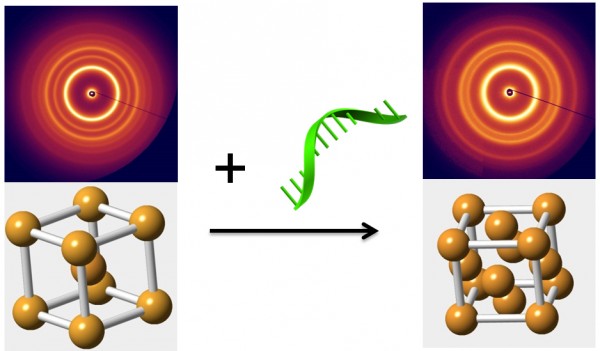

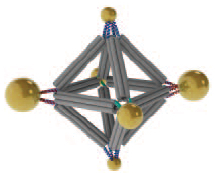

Cluster assembled from DNA-functionalized gold nanoparticles on vertices of a octahedral DNA origami frame (credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory))

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and collaborators have developed a method using DNA for designing new customized materials with complex structures for applications in energy, optics, and medicine.

They used ropelike configurations of DNA to form a rigid geometrical framework and then added dangling pieces of single-stranded DNA to glue nanoparticles in place.

The method, described in the journal Nature Nanotechnology, produced predictable geometric configurations that are somewhat analogous to molecules made of atoms, according to Brookhaven physicist Oleg Gang, who led the project at the Lab’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN).

“While atoms form molecules based on the nature of their chemical bonds, there has been no easy way to impose such a specific spatial binding scheme on nanoparticles, he said. “This is exactly the problem that our method addresses.

“We may be able to design materials that mimic nature’s machinery to harvest solar energy, or manipulate light for telecommunications applications, or design novel catalysts for speeding up a variety of chemical reactions,” Gang said.

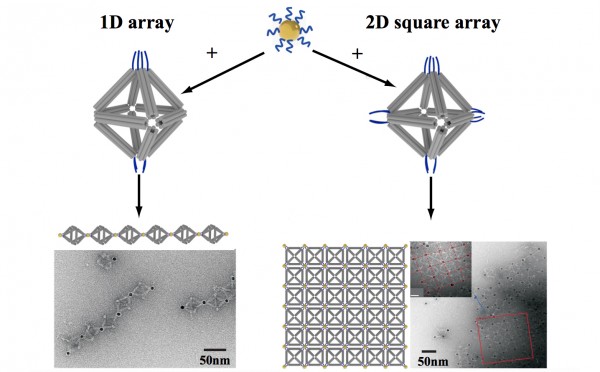

As a demonstration, the researchers used an octahedral (eight-sided) scaffold (structure) with particles positioned in precise locations on the scaffold according to specific DNA coding. They also used the geometrical clusters as building blocks for larger arrays, including linear chains and two-dimensional planar sheets.

“Our work demonstrates the versatility of this approach and opens up numerous exciting opportunities for high-yield precision assembly of tailored 3D building blocks in which multiple nanoparticles of different structures and functions can be integrated,” said CFN scientist Ye Tian, one of the lead authors on the paper.

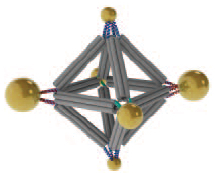

A new DNA “origami” kit

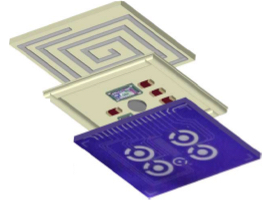

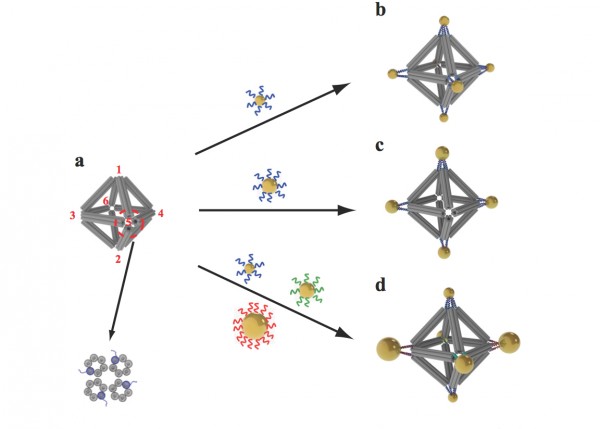

Scientists built octahedrons using ropelike structures made of bundles of DNA double-helix molecules to form the frames (a). Single strands of DNA attached at the vertices (numbered in red) can be used to attach nanoparticles coated with complementary strands. This approach can yield a variety of structures, including ones with the same type of particle at each vertex (b), arrangements with particles placed only on certain vertices (c), and structures with different particles placed strategically on different vertices (d). (credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory)

This nanoscale construction approach takes advantage of two key characteristics of the DNA molecule: the twisted-ladder double helix shape, and the natural tendency of strands with complementary bases (the A, T, G, and C letters of the genetic code) to pair up in a precise way.

Here’s how the scientists built a complex structure with this “DNA origami” kit:

1. They created bundles of six double-helix DNA molecules.

2. They put four of these bundles together to make a stable, somewhat rigid building material — similar to the way individual fibrous strands are woven together to make a very strong rope.

3. They used these ropelike girders to form the frame of three-dimensional octahedrons, “stapling” the linear DNA chains together with hundreds of short complementary DNA strands. (“We refer to these as DNA origami octahedrons,” Gang said.)

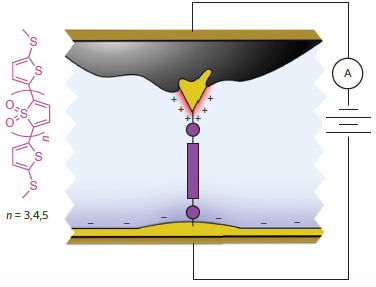

4. To make it possible to “glue” nanoparticles to the 3D frames, the scientists engineered each of the original six-helix bundles to have one helix with an extra single-stranded piece of DNA sticking out from both ends.

5. When assembled into the 3D octahedrons, each vertex of the frame had a few of these “sticky end” tethers available for binding with objects coated with complementary DNA strands.

“When nanoparticles coated with single strand tethers are mixed with the DNA origami octahedrons, the ‘free’ pieces of DNA find one another so the bases can pair up according to the rules of the DNA complementarity code. Thus the specifically DNA-encoded particles can find their correspondingly designed place on the octahedron vertices,” Gang explained.

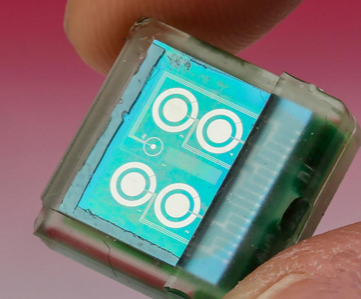

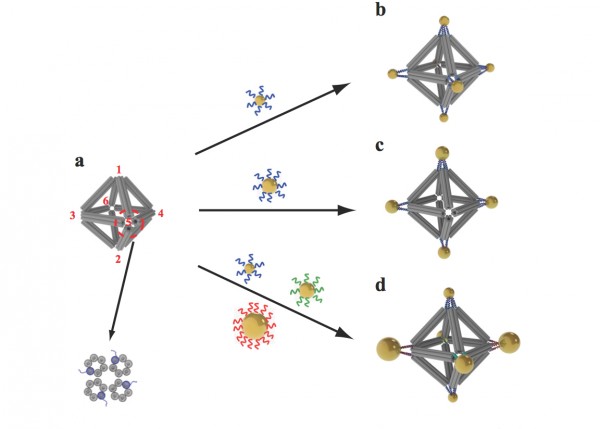

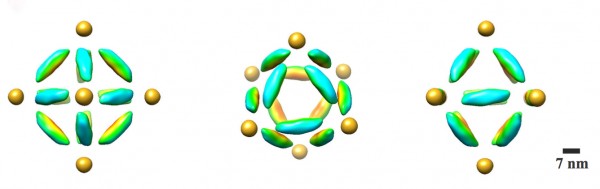

A combination cryo-electron microscopy image of an octahedral frame with one gold nanoparticle bound to each of the six vertices, shown from three different angles. (Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory)

The scientists can also change what binds to each vertex by changing the DNA sequences encoded on the tethers. In one experiment, they encoded the same sequence on all the octahedron’s tethers, and attached strands with a complementary sequence to gold nanoparticles. The result: One gold nanoparticle attached to each of octahedron’s six vertices.

In additional experiments,the scientists changed the sequence of some vertices and used complementary strands on different kinds of particles, illustrating that they could direct the assembly and arrangement of the particles in a very precise way.

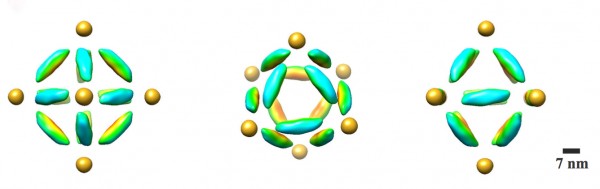

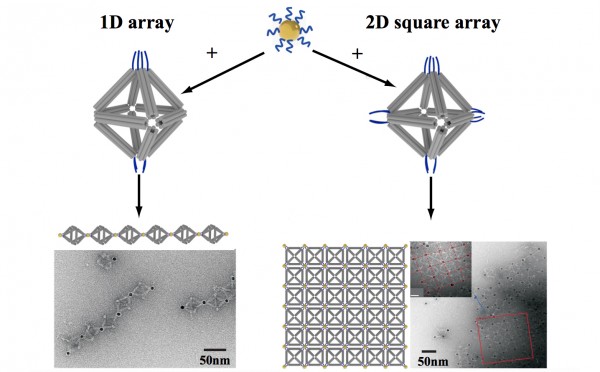

By strategically placing tethers on particular vertices, the scientists used the octahedrons to link nanoparticles into one-dimensional chainlike arrays (left) and two-dimensional square sheets (right). (Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory)

In one case, they made two different arrangements of the same three pairs of particles of different sizes, producing products with different optical properties. They were even able to use DNA tethers on selected vertices to link octahedrons end-to-end, forming chains, and in 2D arrays, forming sheets.

Visualizing the structures

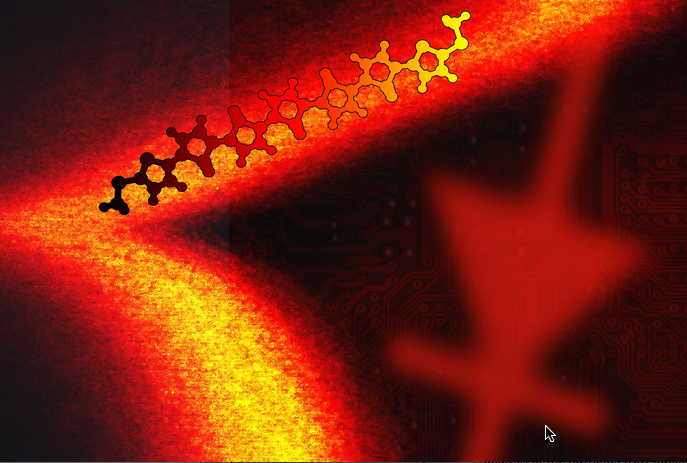

TEM image of part of the 1D array (credit: Brookhaven National Lab)

Confirming the particle arrangements and structures was a major challenge because the nanoparticles and the DNA molecules making up the frames have very different densities. Certain microscopy techniques would reveal only the particles, while others would distort the 3D structures.

To see both the particles and origami frames, the scientists used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), led by Brookhaven Lab and Stony Brook University biologist Huilin Li, an expert in this technique, and Tong Wang, the paper’s other lead co-author, who works in Brookhaven’s Biosciences department with Li.

They had to subtract information from the images to “see” the different density components separately, then combine the information using single particle 3D reconstruction and tomography to produce the final images.

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science.

Abstract of Prescribed nanoparticle cluster architectures and low-dimensional arrays built using octahedral DNA origami frames

Three-dimensional mesoscale clusters that are formed from nanoparticles spatially arranged in pre-determined positions

can be thought of as mesoscale analogues of molecules. These nanoparticle architectures could offer tailored properties

due to collective effects, but developing a general platform for fabricating such clusters is a significant challenge. Here, we

report a strategy for assembling three-dimensional nanoparticle clusters that uses a molecular frame designed with

encoded vertices for particle placement. The frame is a DNA origami octahedron and can be used to fabricate clusters

with various symmetries and particle compositions. Cryo-electron microscopy is used to uncover the structure of the DNA

frame and to reveal that the nanoparticles are spatially coordinated in the prescribed manner. We show that the DNA

frame and one set of nanoparticles can be used to create nanoclusters with different chiroptical activities. We also show

that the octahedra can serve as programmable interparticle linkers, allowing one- and two-dimensional arrays to be

assembled with designed particle arrangements.