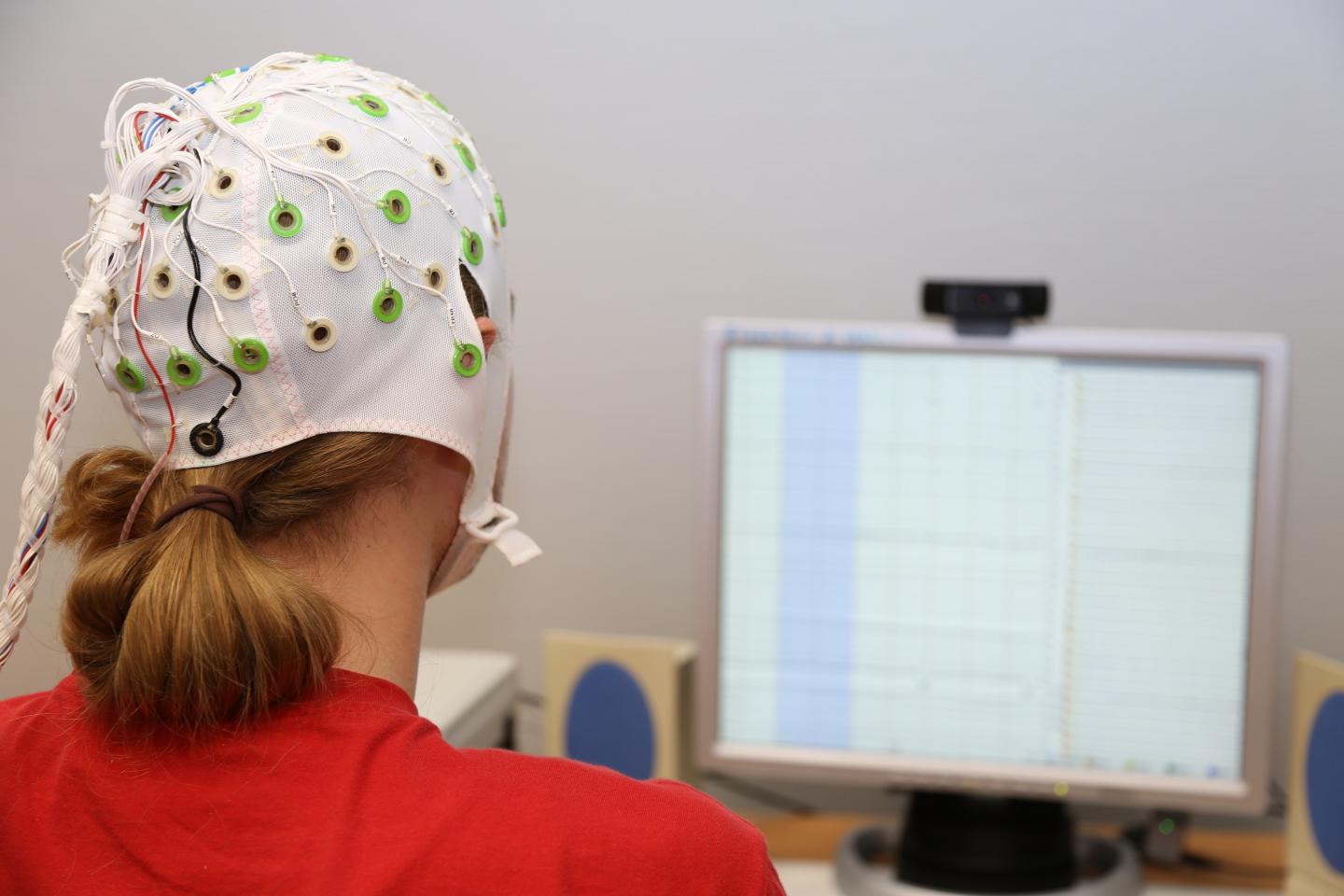

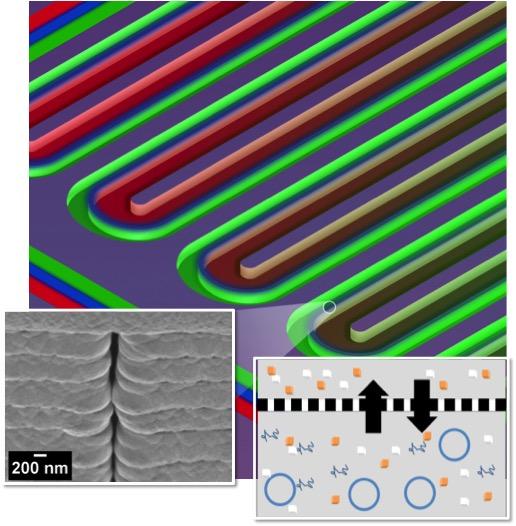

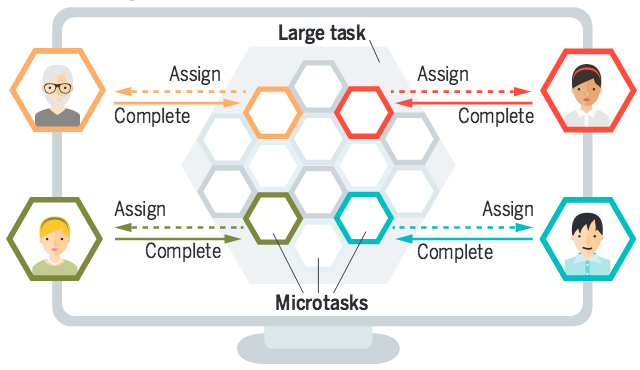

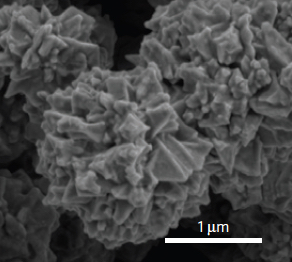

Stanford researchers have developed a thin polyethylene film that prevents a lithium-ion battery from overheating, then restarts the battery when it cools. The film is embedded with spiky nanoparticles of graphene-coated nickel. (credit: Zheng Chen)

Stanford researchers have invented a lithium-ion battery that shuts down before overheating to prevent the battery fires that have plagued laptops, hoverboards and other electronic devices. The battery restarts immediately when the temperature cools.

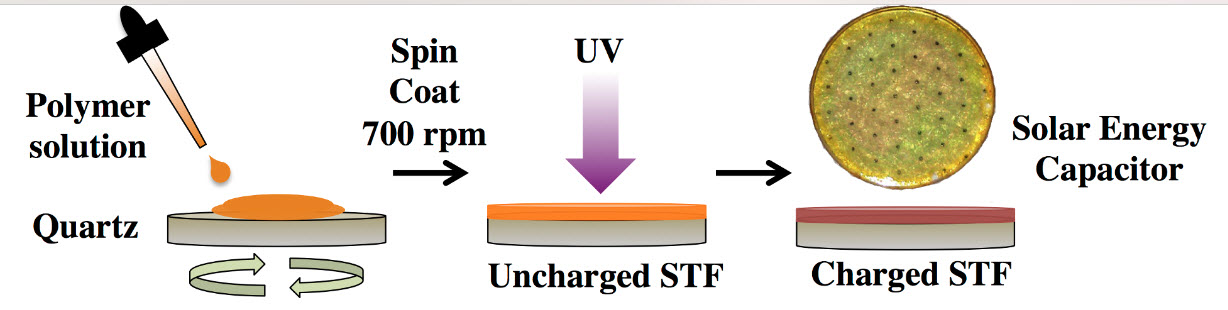

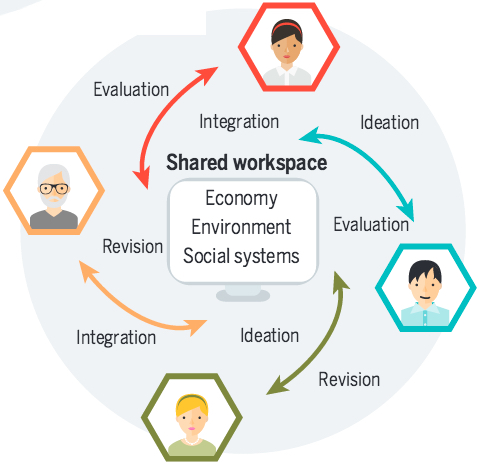

The design is an enhancement of a wearable sensor that monitors human body temperature invented by Zhenan Bao, a professor of chemical engineering at Stanford. The sensor is made of a plastic material embedded with tiny particles of nickel with nanoscale spikes protruding from their surface. For the battery experiment, the researchers coated the spiky nickel particles with graphene, an atom-thick layer of carbon, and embedded the particles in a thin film of elastic polyethylene.

SEM image of conductive spiky graphene-coated nickel nanoparticles (credit: Zheng Chen et al./Nature Energy)

To conduct electricity, the spiky particles have to physically touch one another. But during thermal expansion, polyethylene stretches. That causes the particles to spread apart, making the film non-conductive so that electricity can no longer flow through the battery. When the battery cools, the polyethylene shrinks, bringing the particles in contact again and causing the battery to generate power.

The new battery design has up to 10,000 times higher temperature sensitivity than previous switch devices, and the temperature range can be adjusted by changing the particle density or type of polymer.

“We’ve designed the first battery that can be shut down and revived over repeated heating and cooling cycles without compromising performance,” says Bao. The new battery is described in a study published today (Jan. 11) in the new journal Nature Energy.

Delvon Simmons | My hover board on fire

A typical lithium-ion battery today consists of two electrodes and a liquid or gel electrolyte that carries charged particles between them. Puncturing, shorting or overcharging the battery generates heat. If the temperature reaches about 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius), the electrolyte could catch fire and trigger an explosion, as some hoverboard users have recently discovered.

The research was supported by the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford.

Stanford Precourt Institute for Energy | A lithium-ion battery that shuts down before overheating, then restarts immediately when the temperature cools.

Abstract of Fast and reversible thermoresponsive polymer switching materials for safer batteries

Safety issues have been a long-standing obstacle impeding large-scale adoption of next-generation high-energy-density batteries. Materials solutions to battery safety management are limited by slow response times and small operating voltage windows. Here we report a fast and reversible thermoresponsive polymer switching material that can be incorporated inside batteries to prevent thermal runaway. This material consists of electrochemically stable graphene-coated spiky nickel nanoparticles mixed in a polymer matrix with a high thermal expansion coefficient. The as-fabricated polymer composite films show high electrical conductivity of up to 50 S per cm at room temperature. Importantly, the conductivity decreases within 1 s by seven to eight orders of magnitude on reaching the transition temperature and spontaneously recovers at room temperature. Batteries with this self-regulating material built in the electrode can rapidly shut down under abnormal conditions such as overheating and shorting, and are able to resume their normal function without performance compromise or detrimental thermal runaway. Our approach offers 1,000–10,000 times higher sensitivity towards temperature changes than previous switching devices.